Analyzing the tension between political popularity and economic growth in Indonesia.

Indonesia, as some scholars such as Professor Steven Fish of UC Berkeley and Professor Danielle Lussier of Grinell College have said, should never have been a democracy. After the fall of the country’s dictator Suharto in 1998 following a severe economic crisis, Indonesia was the last country a political scientist would have predicted to transition into a consolidated democracy as it did not have the cultural, historical or institutional prerequisites. While scholars such as Professor Fish and Lussier have explained Indonesia’s relatively robust democratization through the lens of a vigorous civil society, Indonesia is now at a crucial fork in the road. The robustness of Indonesian democratization does not imply robustness in the quality of governance. The tension between political popularity and economic growth in secular Indonesia, the world’s most populous Muslim country, has been to the detriment of the country in its effort to transform a consolidated democracy into a governmental framework that also provides quality governance in the countries aim to take advantage of its favorable demographics, rich natural resources and cultural diversity. Thus, the alignment of political popularity and economic growth through the institutional reform of Indonesian politics should be on top of President Joko Widodo’s agenda.

Upon first thought, the asymmetry between economic growth and political popularity is without a doubt unintuitive, as common sense would dictate that economic growth is inherently tied to political popularity. Why is this not the case in Indonesia? Why are leaders who do not have merit in delivering economic growth or even have economic growth anywhere in their agenda continually being voted in?

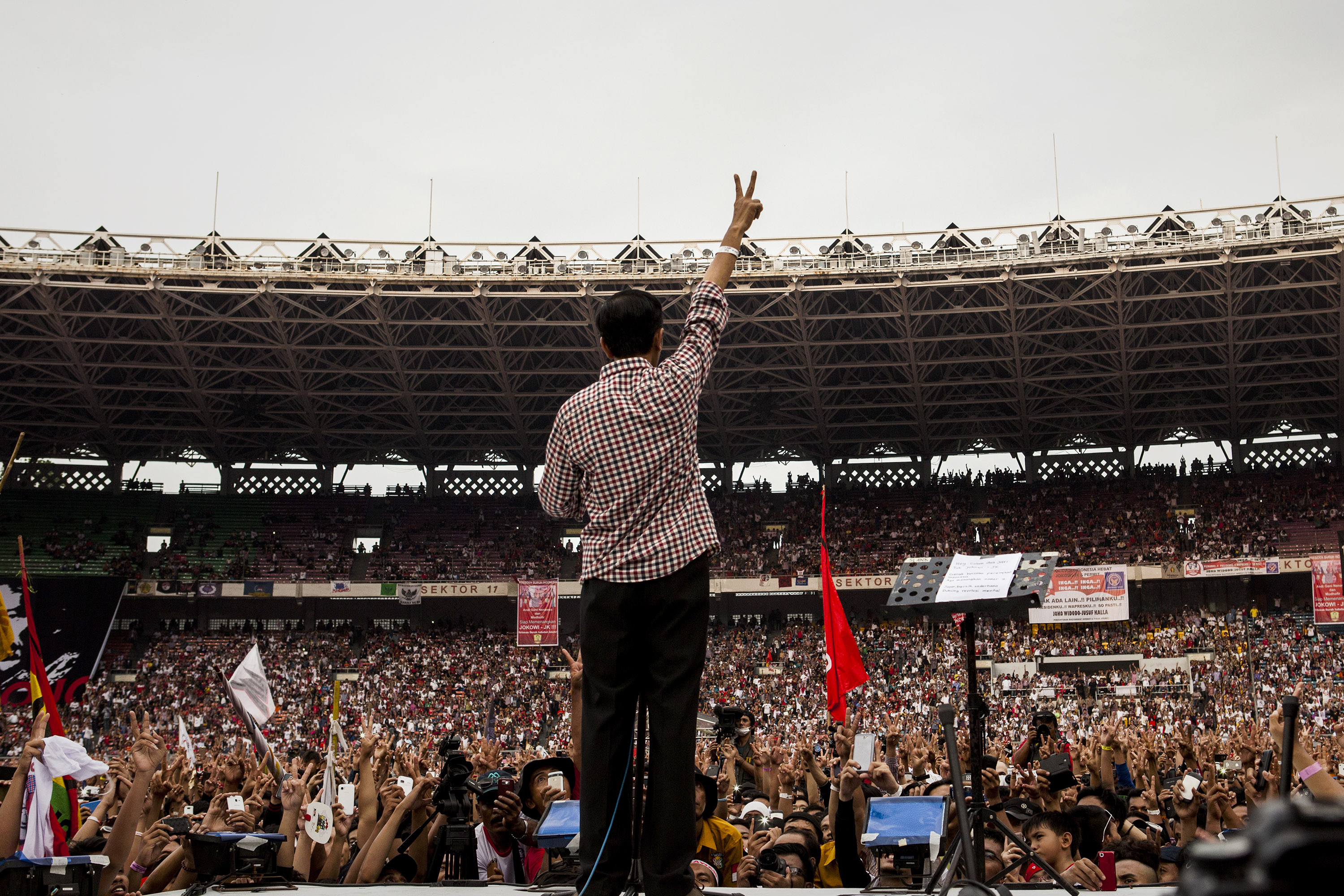

The first reason is perhaps that Indonesian politicians have been unbelievably successful at making politics a battle between personality cults instead of a debate over policy. In fact, one Berkeley professor noted that Indonesians have a remarkable “fetishism for family names” in response to a question about Indonesian voting behavior. In the lead up to elections, at any level of government, there is a distinct lack of discourse over policy or credentials. Instead, debate is centered on personalistic attacks. The personalistic trait of Indonesian politics is perhaps most evident in the 2014 presidential elections. The campaigns ran by both Joko Widodo or Jokowi as he is affectionately known centered around how he was a political outsider who did not have connections towards the political establishment of which the Indonesian public was tired of. Conversely Jokowi’s opposition, Prabowo Subianto’s, campaign centered on his credentials as an ex-general and how he would be a “strong” leader for the country. It is important to note that there was some discussion of policy, however the main storylines of the elections were not Jokowi’s promise of investment in infrastructure or Prabowo’s proposed aggressive and nationalistic foreign policy, instead it was the debate between the political outsider against a member of the political elite. Furthermore, the saturation of political power within media barons is the largest concern regarding the quality of Indonesian democracy. Almost every major news source is owned by someone who either has founded a political party or have made their political interests clear thus further perpetuating the cycle of personalistic politics during election time when the media simply becomes a vehicle of political interests. A change in the way information is disseminated and more regulation of the media sector would go a long way in remedying the personalistic nature of Indonesian politics.

Another factor for the asymmetry in interest is the inherently flawed Indonesian political system. After the fall of the authoritarian regime of Suharto, Indonesia went from one of the most centralized countries in the world where there was an over saturation of power at the presidential level to one of the most decentralized countries in the world where political power was diluted. While taking cue from Bertrand Russell and his prescription for the dilution of political power, Indonesia has overreached in its decentralization thus making it hard to achieve an overarching national agenda.

Indonesians have seven elections in a 5-year political cycle, making it one of the most active political societies in the world. However, the unintended effect of this is that it leads to atrophy in the interest in politics for an average citizen. The average person is unlikely to follow the progress of all seven of the people they vote into office. The atrophy in political interest coupled with the distortion in political information caused by the absence of a credible news source is an incredibly powerful mix that blunts the mechanism and concept of accountability within Indonesian politics. The corrosion of accountability within Indonesian politics makes it so that politicians have not been punished for a lack of performance or corruption. Indonesia is a notoriously corrupt country, scoring 36 out of 100 on the Corruption Perception Index and is ranked 86th in the world in corruption. Besides the degradation of accountability in Indonesian politics, the decentralization in power also perpetuates corruption on every level of government. The complex and messy nature of Indonesian politics makes it almost impossible to regulate. The Indonesian government itself does not know how many districts the country has, as its latest estimate is 497 to 506 districts. That shocking tidbit is perhaps an apt symbol of why corruption in Indonesia has been so hard to stop. Indonesian politics has become too decentralized and regulation of corruption is a losing battle.

But why does corruption matter within the framework of the tensions between political popularity and economic growth? Put simply, it is because corruption, especially on a micro politics level leads to the perpetuation of the pursuit of political popularity while forgetting economic growth. Corruption essentially creates and then widens the cleavage between political growth and economic growth. The cleavage between the political popularity and economic growth starts with the concentration of the government’s budget within the regional level. 90% of the government budget is given by the central government to district governments to perform almost 100% of government services, which include healthcare, education, and basic sanitation needs. Political offices then become very economically lucrative, thus attracting people who are perhaps not in it for governance but a share of the spoils. Politicians are then less likely to focus on national economic growth, as their focus will be on gaining political popularity to either retain office or get into office. Due to the way the budget is distributed and the erosion of accountability, winning political office in Indonesia has become a battle for the economic spoils of office. This also creates a culture of patronage and breeds an unhealthy relationship between the private sector and governance. Politicians who want to run for office or stay in office are bankrolled by the private sector as they expect returns when the politician is in office in the form of favorable policies and government contracts. This unhealthy cycle essentially locks people who do not have favorable connections with people in power out of business opportunities and from then contributing to economic growth. This then furthers the tension between economic growth and political popularity as a rent-seeking economy is created where a select few are continually exploiting other’s share of the economic pie instead of growing the economic pie. Therefore, the central government would find it hard to push through an overarching agenda of economic reform as politicians are too focused on retaining or achieving access to the spoils of political office by prioritizing political popularity over economic growth.

While the analysis above has been somber in nature, there is hope for Indonesia as there are signs that the public awareness of issues has started a push for a re-alignment of political interests and economic growth. This fact is perhaps most evident after the election of President Jokowi, who has begun pushing through economic reform to the approval of Indonesians and world markets. The index for the Jakarta stock market, which is hardly known to be a growth heavy investment has outperformed expectations and is one of the ten best performing stock markets in the world. As Indonesians become more politically aware, the degradation of the mechanism and concept of accountability should be reversed, as politicians will start to be held more accountable for their performance in office.

More importantly, what President Jokowi and his mandate to revolutionize Indonesian politics can do is structurally reform the political system. There are many ways to fix the problem caused by decentralization, be it centralizing power or making the mechanism of regulation stronger to prevent abuses of political power. According to a Berkeley professor, the centralization of power while appealing and the “easy fix” is a rather unappealing option due to the influence the military still holds within governance.

With this in mind perhaps the most important reform is one that is already happening, and that is the increase in political education and awareness among the voting Indonesian public who are prioritizing economic growth and punishing corruption and poor performance. Structurally, to borrow from Professor Peter Evans, President Jokowi needs to set up institutions and laws to implement Professor Evans’ concept of embedded autonomy. The concept of embedded autonomy is that economic growth will come when bureaucratic autonomy and societal of the bureaucracy embeddedness co-exist. This is done through an independent government providing an institutional framework of communication with society and the private sector to continually discuss goals and policies instead of the Indonesian style of politics today where the private sector holds an unhealthy amount of influence in government and where the interaction between the public and private sector is messy and unregulated. The implementation of embedded autonomy would lead to the degradation of patronage politics and the hazardous and toxic link between the private sector and governance as this interaction would now be regulated under an institutional framework. By implementing these reforms, President Jokowi can seize upon the momentum of political opinion towards the alignment of political popularity and economic growth and institutionalize the re-alignment of interests to consolidate growth in Indonesia’s economy and democracy.

Therefore, what Indonesia needs is a fundamental shift in politics, not just the politicians in power. President Jokowi is now in power during a seminal moment of Indonesia’s development and should make it his priority to fix the misalignment to deliver on his promise of economic growth. For the global community, the promise of Indonesia as a model democracy still stands, however it hinges on the resolving of tensions between political popularity and economic growth. Ultimately, Indonesia’s future is in the hands of the voters such as myself who must continue to hold politicians accountable and push for quality governance.

Featured image source: Oscar Siagian/Getty Images

Be First to Comment