On January 9th, 1966, the New York Times Magazine published an article by sociologist William Petersen called “Success Story, Japanese-American Style.” In the article, Petersen wrote that Japanese-Americans, despite enduring the “most discrimination and the worst injustices” of WWII-era internment, have achieved great success in America “by their own almost totally unaided effort.” Petersen goes on to claim that this success was driven by the Japanese’s strong work ethic, family values, and respect for authority, while pointedly noting the lack these same traits in African-Americans.

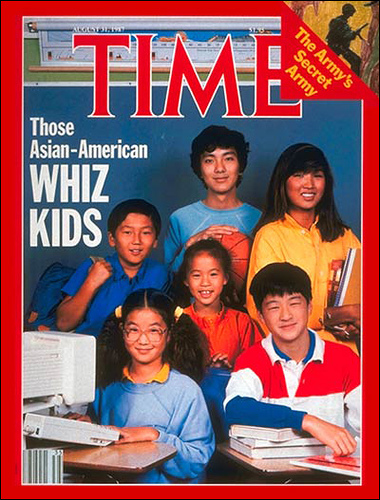

Petersen’s article introduced the “model minority” concept in American political discourse in an era of the Civil Rights Movement and the Johnson Administration’s “Great Society” programs geared towards eliminating racial injustice. Primarily citing Japanese-Americans’ higher educational attainment as emblematic of the population’s success, Petersen argued that their cultural values prevented them from becoming a “problem minority”; unsurprisingly, the study went on to be utilized by the opponents of the Civil Rights Movement, who argued that African-American communities could achieve similar success by conforming to the preexisting structure of governance and focusing on education.

Hidden under the praise of high educational attainment, Petersen’s notion of the model minority embodied a minority population’s strikingly apolitical presence in America. And in fifty years of progress in racial equality, nothing much has changed for Asian-Americans.

The American media today portrays Asian-Americans as extremely studious and intelligent, but socially awkward and quiescent. The math-nerd with glasses who can’t function as a normal human being around the opposite sex; the dude with a runny nose and a lisp who gets bullied by the “cool kids,” but wins all the math and science Olympiads to end up at Stanford University with a full scholarship—we all know who I’m talking about.

Such comical portrayals aside, the generalized statistics of numerous studies do often enumerate a prominent presence of Asian-Americans in America’s elite universities, highest median household income, as well as their lowest total arrest rates among all racial groups. Combined with the presence of segregated Asian enclaves—such as Chinatowns, Koreatowns, and Little Saigons—and a much less prominent history of political activism, these portrayals have cemented Petersen’s “model minority” into the minds of the American public.

This “positive stereotyping” has alienated the Asian-American population from the discussion of racial discrimination in America, and for predictable reasons. As evidenced by Petersen, Asian-Americans are perceived as a population without any needs for government support.

One article published by the Washington Post states, “the idea that Asian-Americans are distinct among minority groups and immune to challenges faced by other people of color” has come to a prominent existence in American domestic politics. The deeply ingrained cultural perception of the model minority acts as a blanket statement for Asian-Americans who hail from over 50 nations. And when incredibly diverse groups of people are lumped together under the banner of “They’re Rich, Educated, and Successful,” poor policy implications are bound to arise.

“When you break it down by specific ethnic groups, the Hmong, the Bangladeshi, they have poverty rates that rival the African-American poverty rate,” said Algernon Austin, the director of the Race, Ethnicity and the Economy Program at the Economic Policy Institute, in a 2013 interview with NPR. “Because there is a high median family income [for Asian-Americans], it’s harder to get the resources and the services to low income Asian-American communities.”

Admittedly, the stereotype of high educational attainment does hold true for a significant percentage of the Asian-American population. Asian cultures have historically placed a strong emphasis on the value of education, self-discipline, and obedience, with education presented as a singular source of social mobility. Strict demands and expectations for academic excellence are pervasive within a striking number of Asian-American households, which, in turn, do successfully push Asian-American students to produce above-average scores on standardized tests.

However, what the American public often forgets is that Asian-American students are subject to intense verbal and physical harassment based on their appearance, school performance, and accents. In a study conducted by New York University’s Susan Rakosi Rosenbloom and Niobe Way, Asian-American students in urban high schools described experiences of racial slurs, teasing, and physical harassment—in horrendous forms such as being randomly slapped in hallways—more than other racial groups.

Nevertheless, despite the simultaneous overexposure of Asian-American students to sometimes socially abusive environments and hypercompetitive academic pressures, the issue of mental health remains an invisible elephant in the room. Despite the consistent findings that Asian-Americans exhibit higher rates of depression and anxiety than their white counterparts, these symptoms often go unaddressed due to the sharp stigma and shame associated with mental illnesses. And the pressure to live up to the “model minority” stereotype is a predominant source of this shame. Asian-American students, who are viewed as immune to the struggles of racial discrimination and bias, are often under intense pressure to pretend like everything is fine—to embody academic success, assimilation to American culture, calm composure, and bright futures. To be anything less is widely regarded as to be a failure, from both within and outside of the Asian-American communities.

“I don’t want to rock the boat,” said Emily (a pseudonym), a Chinese-American student at the University of California, Berkeley, who wished to stay anonymous. “Yes, depression and anxiety are serious issues, but I deal with it and move on. At the end of the day, I don’t think there’s anything you can do but work harder. I have working class parents who have worked so hard to send me to college, so I can’t afford to not succeed because I have emotional problems.”

The demands for excellence and an emphasis on work ethic bring numerous Asian-American students to top elite universities. In top public universities in California, where admissions based on racial criteria are prohibited, Asian-American students constitute a staggering percentage of the student body—42.9% in University of California, Berkeley, and 45% in California Institute of Technology.

But the statistics show a strikingly opposite representation of Asian-Americans in the workplace. In a 2015 article, the Economist notes “27% of professionals, 19% of managers and 14% of executives were Asian-American.” In addition, in 2014, “whereas 11% of law-firm associates were Asian, 3% of partners were.” The lack of representation continues at the top, where in the span of 14 years the number of Asian-American CEOs rose from eight to ten while “the women’s tally in the same period rose from four to 24.”

Even in the technology industry, in which Asians stereotypically dominate, there is a noticeable absence of Asian-Americans in the upper echelons. In 2013, Business Insider took the New York Times data of 200 highest paid executives in the world and filtered it to only include twenty-eight CEOs that ran technology companies. The result was that only one of those twenty-eight—Shantanu Narayen, an Indian American CEO of Adobe Systems—was Asian. So where do all the Asian-American software engineers go?

In her 2005 book, author and executive coach Jane Hyun first coined the term “bamboo ceiling” for this invisible barrier that stumps Asian-Americans in the workplace. A parental phrase, called the “glass ceiling,” is much more frequently used in modern political discourse as an umbrella term that affects women and various minority groups. However, despite their underrepresentation in professional realms, Asian-Americans remain soundly—and paradoxically—excluded from the modern American discourse on workplace representation.

The model minority stereotype has obscured the perspective of the American public, keeping them from embracing the Asian-American struggle. Horrifying racial violence against Asian-Americans was rampant in American history, but American textbooks acknowledge practically none of it. The Chinese massacre of 1871, in which seventeen Chinese residents of Los Angeles were lynched, is practically unknown to today’s mainstream activists for racial equality. The 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American man who was beaten to death in the suburb of Detroit by two white men, was not enough to remind Americans that Asians, too, have been victims of racially charged physical violence.

The necessity to acknowledge, and fight against, the racial discrimination experienced by the Asian-American population does not delegitimize the magnitude and the severity of the struggles experienced by African-Americans today. Rather, it is an acknowledgement that racism exists in diverse and nuanced forms in America. Indiscriminate murder of African Americans is, indeed, a life-threatening issue that must be addressed with urgency; however, to perpetuate a stereotype that Asian-Americans are uniformly well-educated, wealthy, and free from oppression, is to perpetuate an equally dangerous disguise that hides the poverty, mental illnesses, and racial discrimination that plague Asian-American populations today. Perhaps, in order for Asian-Americans to be acknowledged as human beings—just as imperfect, struggling, and fraught as members of other races—the boat has to be rocked.

Featured image source: TIME Magazine.

One Comment