Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died peacefully two weeks ago, but two hours later discord erupted among the GOP, the election campaigns and the Senate over his replacement.

Republican leaders on the campaign trail and in the Senate have said the next president should appoint his replacement, or have called for delays or obstruction of any nominee President Obama puts forward. Republicans control the U.S. Senate which must approve Supreme Court nominees. They believe the next president could be a Republican who would nominate a conservative replacement for Scalia, instead of the liberal Obama is likely to nominate. Democratic leaders have lobbed back that this “partisan sabotage“can only harm them. Seemingly, everyone else is throwing around opinions over whether this is good or bad for Republicans and Democrats.

They have also suggested number after number about how many justices have been confirmed during an election year (six since 1900), how many days lapsed in the longest confirmation process (125 days for Louis Brandeis in 1916) and how many presidents have purposely left a seat vacant until after an election year (zero since 1900, according to SCOTUS blog).

The Senate has the power to refuse to hold confirmation hearings before the Judiciary Committee and a floor vote on the nominee.

Therefore, any effort to replace Scalia depends on the political dynamic in the Senate. Right now, Republican priorities continue to dominate the Senate and the party has won several legal victories over the past few years, Non-conservative victories will be highly unlikely currently.

To take just one example, Ted Cruz is right to say that a more liberal replacement for Justice Scalia is very likely to overturn the Supreme Court’s recent recognition of a Second Amendment right to possess firearms or at least render it a nullity as a practical matter.

The real issue is that there are no established measures for dealing with election year vacancies. Thus, partisans on both sides can propose their own understandings of the history of the court to bolster their arguments on Obama’s eventual nominee as well as the proper procedure for nominations.

There are less than a handful of precedents to this situation that are akin to Scalia’s death. One such case arose when Chief Justice Warren asked to retire in 1968. President Johnson nominated Justice Fortas. As it was an election year, conservative southern Democrats and Republicans joined forces to successfully block Fortas with filibuster after filibuster in the Senate.

Strom Thurmond, a segregationist South Carolina senator, led the efforts to stymie Fortas, invoking what has since been become known informally as the “Thurmond Rule”. This is the non-binding and informal Senate tradition of resisting Supreme Court appointments in the final six months of a presidency that McConnell and other Republicans have essentially been alluding to since Saturday. The pressure was so great that Johnson withdrew the nomination a few months later and Warren was forced to remain as chief justice.

In general, the president’s nominees are confirmed and the balance generally tips towards the President. According to Princeton University historian Kruse, the “general rule, informal at that, is that a president shouldn’t make nominations in the last six months of his term — but we’re well outside that window. Republicans have every right to block specific nominees, but we’ve never seen a blanket claim that they just wouldn’t consider anyone for nearly a year before.”

According to the Congressional Research Office, the average time from nomination to confirmation for a Supreme Court justice was 59 days between 1900 to 1980. Although this duration nearly doubled in the period from 1980 to 2010, ballooning to 113 days, a holdout over Scalia’s seat for the remainder of Obama’s term, 341 days from his death, would more than triple the current average and drift quite near to the Fortas record.

Nevertheless, Fortas’ record vacancy was not a product of the Thurmond Rule or any sort of constitutional standard that negated a president’s ability to nominate as a “lame duck”. Rather, a matter of the normal partisan political maneuvering has defined Supreme Court confirmations for at least the last century. However, once the political grandstanding quietens down, this less extraordinary process that will dictate the timing of Scalia’s replacement. The president has a duty to realize and fill any vacancy on the court with a nomination. What the Senate does with it is then up to pure politics.

Putting the absurdities and vehement sentiments of both sides of the Senate, what would Scalia say about a 4-4 split, that could possibly gridlock and table the upcoming hearings? In short, what would Scalia say about replacing Scalia?

A 4-4 gridlock was in Scalia’s opinion, incredibly harmful to the court. In Cheney v. United States District Court for the District of Columbia, 541 U.S. 913, 915 (2004): Let me respond, at the outset, to Sierra Club’s suggestion that I should “resolve any doubts in favour of recusal.” … That might be sound advice if I were sitting on a Court of Appeals. There, my place would be taken by another judge, and the case would proceed normally. On the Supreme Court, however, the consequence is different: The Court proceeds with eight Justices, raising the possibility that, by reason of a tie vote, it will find itself unable to resolve the significant legal issue presented by the case.”

Scalia is right. The close ideological divide on the Supreme Court is dependent on the nominee that fills the vacancy caused by Scalia’s death. Action could very well stall on a series of important cases, including major upcoming rulings on abortion rights, Obama’s Clean Power Plan to combat climate change, and the legality of his executive actions on immigration. When the liberal-conservation 4-4 split occurs, and it most likely will, the ruling of these cases now transfers to the lower court. The federal courts now have the power to dictate outcomes tantamount to the entire nation.

We can all laugh at and poke fun of the ridiculousness of this debacle. And. But this is not the first issue that the Senate and the Supreme Court has not been able to solve. Scalia’s death is the latest farce to reach the public that highlights a long history of the Senate’s inability and the lack of legal provisions to deal with unexpected crises. That speaks to not only the failures of the system itself but also to those that maintain and prolong the inefficiencies of it. Scalia, a judge whose controversial views, sharp wit and writings, made him a source of debate, is gone. Nevertheless, the bitter political controversy around the Supreme Court and its nominees will only intensify.

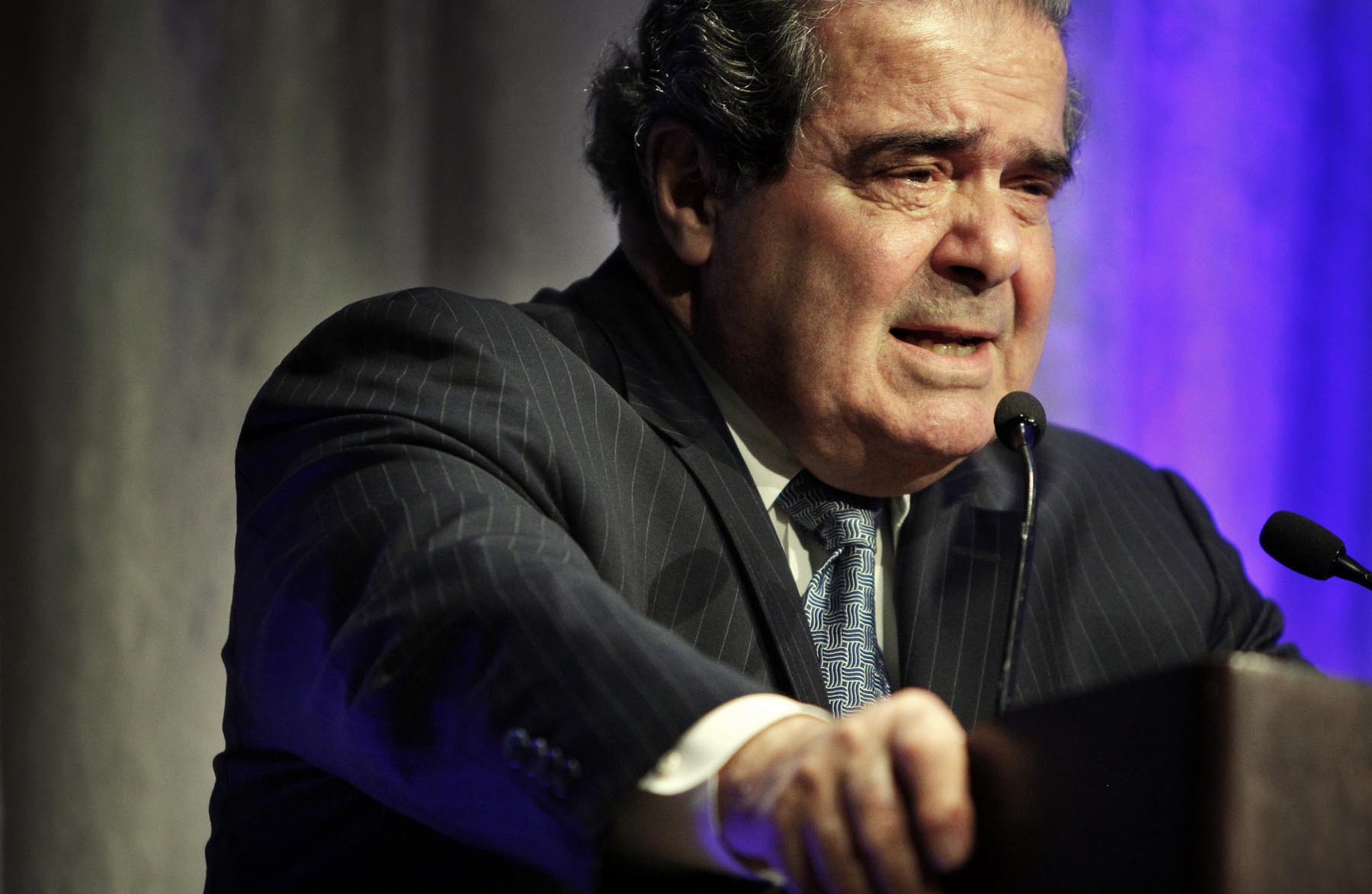

Featured image source: Jim Weber/The Commercial Appeal

Be First to Comment