A few months ago, I had the opportunity to shadow an oncologist, a physician who treats cancer patients. From day one, he emphasized how much suffering there was in his profession, particularly in his specialty. It was sad to watch these patients agonize through chemotherapy and radiation therapy, as treatment regimens sapped their vitality. As a doctor, he had to lay out all the available options for his patients. He would give recommendations, but sometimes, he had to aggressively treat patients despite the high cost-benefit ratio because of their wishes. They just weren’t ready to accept palliative care, despite the option being on the table. Why? Answering this question is crucial to improving palliative care in the United States.

What really is palliative care?

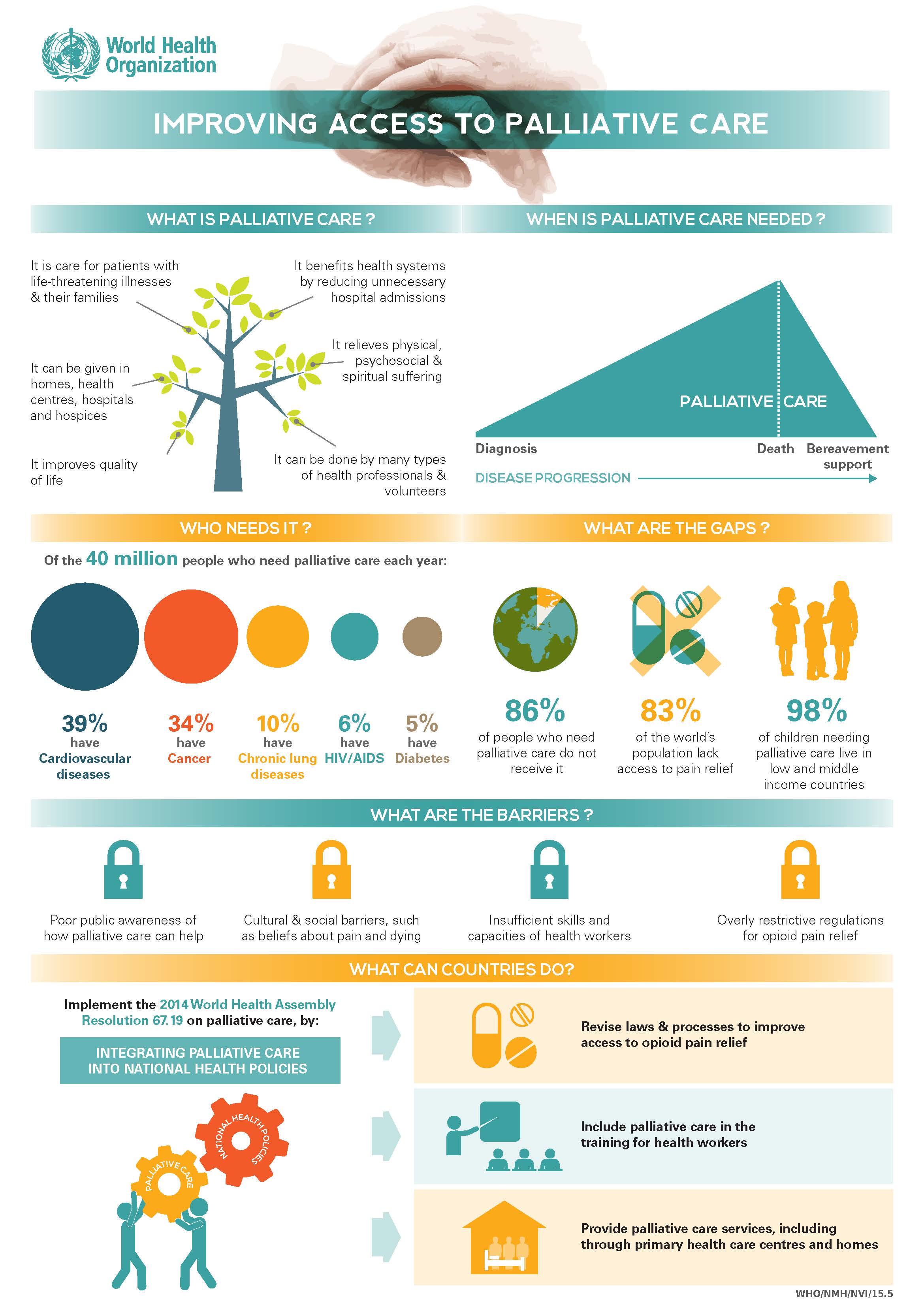

Palliative care is essentially adopting a plan of care that aims to control symptoms and provide physical, psychosocial, and spiritual support to patients as opposed to pursuing aggressive treatment that can often worsen symptoms and pain. Improving the quality of life during a time when the patient is going through health issues is a vital aspect of this type of care.

There are several common misconceptions about palliative care. Many conflate “palliative care” and “hospice care.” Hospice care is certainly oriented in pain management and opted by many patients with terminal illnesses. However, palliative care can be coupled with curative treatments as well, whereas hospice care is not. It is also important to note that “end-of-life care” is not the same thing as palliative care either. Another misconception is that accepting palliative care is the equivalent to “giving up” and accepting imminent death. This is certainly not true; patients simply have more control over their care and comfort and doctors will not pursue the most aggressive treatment plans, rather choosing only treatments that preserve the physical and mental comfort of patients. This is the crux of why an effective palliative care plan is so vital to the well-being of an ailing patient: patients should be able to choose the ratio of curative and symptom-alleviating care they receive.

Policy proposals—from the top down

Currently, our palliative care standards and implementation are not where at a level where most patients are comfortable going with it. As a result, there is unneeded suffering in hospitals across the nation. I therefore propose a four pronged policy approach to improve palliative care standards in the U.S.: education, research, funding, and standardization. Many of these recommendations, particularly in the first 3 categories, are proposed by the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC), but I also believe that standardization is a vital component to tie all these recommendations together and ensure that everyone has equal access to palliative healthcare.

First, education of both healthcare professionals and the general public is needed to ensure that there is a standard of understanding. This involves expanding the palliative care curriculum in medical schools and even undergraduate pre-medical programs. As of 2014, there is still no mandated palliative care curriculum in medical schools. End-of-life care is part of the curricula, once again illustrating the conflation of these speciously similar terms. According to a study by Horowitz, Gramling, and Quill, teaching of palliative care and end-of-life care in medical schools ranged from just a couple hours of lecture to weeks of both classroom and clinical rotations. This massive discrepancy in education is a reason why some healthcare professionals do not feel comfortable recommending palliative measures to their patients. The CPAC recommends the establishment of educational palliative care centers to train healthcare professionals in palliative care skills. Such trainings should be made mandatory for doctors and nurses working with end-of-life patients. These trainings should also be available for medical students, undergraduate pre-medical students, and members of the general public who may want to gain expertise in this specialty to better take care of their loved ones.

It is just as important to educate the general public on what palliative care is. It doesn’t take a healthcare professional to precisely define vaccine or hospice or health insurance. We need to add palliative care to that list. One way to accomplish this is to expand the role of educational palliative care centers to also work to disseminate information to the general public and correct those common misconceptions. I imagine these to be similar to vaccine informational centers, where licensed professionals hired by the government will be responsible for increasing public awareness.

Education alone is not enough; palliative care needs to be optimized in both cost efficiency and efficacy in comfort care and pain management. This can be done through the support of research studies aimed at developing models of palliative care and delivery through both analyzing statistics and communication with patients and their families. Currently, we have standard treatment protocols that physicians use as guidelines for many diseases. These protocols were developed on the backs of many research studies that provided concrete data on which treatments were most effective at various stages of disease. Similar standard operating procedures should be developed for how to most effectively use palliative care to manage symptoms and pain. We need to know which diseases and at what times palliative care is most effective in terms of both prolonging life and reducing debilitating symptoms. Of course, one of the unique things about palliative care is that each patient is treated differently based on their wishes and state of being. This should not change; however, having an overarching roadmap is still nonetheless necessary for the safety of the patient.

Thirdly, lack of funding on both ends of palliative care, physician and patient, needs to be addressed. Congress needs to allocate funding to improve quality and efficiency of palliative treatments. Some doctors are not comfortable with pushing for the use of palliative care not only because they are not adequately trained, but also because there is no standard that can give them the confidence to definitively say that this is the best course of action for their patient. Funding to increase the prevalence and quality of palliative care hospitals can alleviate this concern.

One of the greatest issues is that often, palliative care measures are not covered by private health insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid. When they are, they are often not referred to as palliative care, which not only creates unnecessary confusion, but also makes it so that not all aspects of a complete palliative care plan are covered. For example, some insurances will cover hospice care, but since by definition, hospice care does not include any curative treatments, those who want both comfort care and a measure of curative care would have to choose between the two. Fortunately, there are many insurance companies who are increasing access to palliative care.

Finally, we need to synthesize research results to create standardized palliative care plans implemented across the nation. Currently, standards for palliative care programs not only vary but are also voluntary. Thus, many hospitals do not even have palliative care specialists or nurses and nurse practitioners trained in this specialty. A lack of standardization also means that patients at various hospitals will receive varying degrees of quality of care. Once again, standardization does not not mean that each patient with the same condition should be treated the exact same way, as this goes against the personalized methodology of palliative care. Standardization simply ensures that a minimum standard of care is met so that patients can receive the best guidance possible.

For standardization to be truly effective, insurance plans need to be standardized as well. Much of palliative care is not done in the hospital, because it is a goal to keep patients at home in their normal lives as much as possible. Thus, only by mandating that insurers cover specific out of hospital care such as home visits can we have an overarching minimum standard to maximize the efficiency of palliative care. In addition, grassroots Community Based Palliative Care Centers are an effective way of providing needed services to members of the community. Such centers are beginning to form in California, but has yet to become a staple of medical care.

These four main points are all interconnected so merely focusing on one or two will not improve our palliative care system much. For example, without standardization and research to optimize palliative care, insurance companies will not cover all the costs accrued in one bundle, leaving potentially uncovered parts of the treatment plan. Without education and research, we cannot standardize care plans. Without adequate funding to actually implement changes in clinic and hospital, there is little point in spending money to educate and conduct research.

Individual actions—from the bottom up

Experts in this field, such as Dr. Eric Kessell of the UC Center for Health Quality and Innovation at the UC Office of the President, believe that more can be done by individuals as well. He says that “It is very important to fill out an advanced care directive and have that conversation early with your family, which can be considered as on the continuum of palliative care. You don’t have to be old to do this – it is much better to do so when you aren’t sick.” Having an advanced care directive can prevent complications from disagreements amongst family members and caregivers when one isn’t capable of decision-making anymore. This very short (5-page form for California) form can save much headache and pain down the road.

This may be hard for some to have this conversation, and that’s one of the difficulties of palliative care. However, as Dr. Kessell puts it “People have a hard time inserting [such discussions] into conversation. It can be awkward to bring up, but it’s a relief to be able to know what’s expected of you [later on].” Clearly there is much individual effort concerned with implementing care consistent with individuals’ wishes and some policy should focus on encouraging this because in the long run, it will save much time, money and pain.

Why are we still getting B’s?

We need to also look at underlying reasons that current efforts to improve palliative care are not producing much results. According to the CAPC, one-third of U.S. hospitals still have no palliative care services. The overall grade in palliative care services across the nation in 2015 is still the same B grade in 2011. Though a B grade in healthcare is not bad at all, according to Professor of Health Economics and Public Policy Richard Scheffler of UC Berkeley, what is troublesome is the lack of palpable improvement.

Perhaps the reason that palliative care is so often frowned upon lies in the American culture of victory. The American healthcare system has always promoted pursuing aggressive and front line treatments in order to cure diseases, not just relieve symptoms. Part of the reason is that America has generally been at the forefront of medical technology. As such, the American healthcare system has generally treated death as the worst possible outcome of a disease. The everyday rhetoric of “fighting” and “beating” cancer equates survival with victory. This becomes a problem in a culture where losing is so frowned upon. Is not living out one’s last days in happiness and comfort a victory in its own right? Each patient absolutely should have the choice of pursuing aggressive and experimental treatments. The issue is that they are often at an informational disadvantage because palliative care is not presented to them accurately. Oftentimes, the choice is between treatment, which will hurt and may or may not be effective, and imminent death. When there is no in between, or the in between choice is not presented accurately, the patient is the one who suffers.

A shift in rhetoric is perhaps needed to fully implement effective palliative care in our healthcare system, but I believe that it can be done through increased education to correct misconceptions and public awareness.

Economics is also a large part of why palliative care has not taken off in more rural parts of the country, especially across the South, where most states received a C or D grade from the CAPC. There are large start-up costs associated with implementation of palliative care programs, including expenses for trainings, facility improvements and expansions, and the hiring of licensed professionals. It is difficult to front such large sums of money without government assistance in these areas, even though in the long run, hospitals who have effective palliative care programs more than recoup start-up costs.

Past regrets but a bright future

We are already doing more to advance palliative care in these areas. A PubMed search of “palliative care” yielded 10984 results published between 2005 and 2009 and 15827 results between 2010 and 2014. In 2015 alone there were 4356 publications on palliative care. According to the CAPC, the number of hospital-based palliative care programs has tripled between 2000 and 2010. Preeminent medical schools such as Harvard and Yale have expanded their palliative and end-of-life care curricula in recent years.

My grandma passed away from pancreatic cancer at the age of 69. She spent the last few months of her life undergoing intense chemotherapy and radiation therapy. She was in constant pain and eventually passed away from treatment gone wrong. Would the last few months of her life been much happier and had she received less curative treatments and more comfort care and emotional and psychosocial support from a team of doctors who prioritized her immediate well-being? I’d be willing to bet.

At the end of the day though, it’s up to the patient and immediate family to decide how much treatment the patient would like to get. However, stories like Luz Garcia’s make one wonder why palliative care is a rarity rather than the default. Luz’s husband and daughter disagreed on what last-ditch measures should be taken, if any, to save her. Luz was not consulted and her husband had the power to make the decision to go ahead with immediate kidney dialysis. She tried to resist but the procedure was done anyways. She was gone within 24 hours. Had she on been on a palliative care treatment plan, this situation never would have happened. Only when the majority of the public is comfortable with the palliative care system can we begin considering making such compassionate care the norm. These improvements will go a long way in making this a reality.

Special thanks to:

Richard M. Scheffler, PhD

Distinguished Professor, Health Economics and Public Policy, UC Berkeley

and

Eric Kessell, PhD

Project Consultant at University of California Office of the President

for their expert opinions and consultations.

Featured image source: physiciansweekly.com

One Comment