Aziz Dyab, like millions of his countrymen, was on the run.

On the run from a repressive regime, unthinkable living conditions and little to no prospects for the higher education he so desperately sought. Aziz Dyab, however, would not be held back. He would escape to Turkey, be granted resettlement, and achieving the dream of many embattled Syrians, find his way to Germany.

Today, Dyab studies mechatronics. He sees a bright career for himself. He wants to be an astronaut.

Supported by locals in Frankfurt, Dyab is a glowing example of how refugees might directly become educated, contributing members of an industrialized western economy. However, up until now, stories like Dyab’s, chronicled in Guy Chazan’s Financial Times article, have been overshadowed by the darkest tones of our politics. It seems as though fear mongering, hate-driven, craven dialogue currently drives public discourse. Humanitarian pleas for Syrian refugees are met by proposed bans, generalistic religious tests and outlandish claims.

Professor Mahmood Monshipouri, Professor of International Relations at San Francisco State and Visiting Professor at UC Berkeley, stated in a recent Sustainable Security article that politicizing the refugee crisis in Europe may only be strengthening the hand of the Islamic State and enabling a more salient conversation to be avoided:

“Closing Europe’s porous borders and politicizing the admission of refugees at a time when the growing humanitarian crisis poses mounting human rights challenges to the international community is fundamentally misguided. After all, fortifying European borders, while effective in the short term, strengthens the hands of ISIS and other terrorist groups that portray such policies and practices largely in terms of apocalyptic visions and arcane Islamic prophecies of great battles against Western imperialists.”

This dialogue has become a major point of contention for the two major party presidential nominees. Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton has called for an increase in refugee intake to 65,000, while Republican nominee Donald Trump has lambasted Secretary Clinton for bringing in people who “don’t share our values” and could ostensibly be linked to ISIL.

However, what neither party has saliently addressed on a public platform are the long-run economic effects of refugee intake. In this framework, we can eschew Islamophobic sentiment and engage in dialogue about tangible economic benefits. As the election nears, as Syrians and neighboring nations deal with millions of internally displaced persons, it may be worth reassessing what has been the focus of our national debate.

The crux of the economic debate regarding the refugee crisis, and all mass exoduses of displaced people, can be categorized into two distinct set of political shibboleths. The first is that massive influxes of refugees drag down wages, place a burden on social programs and taxpayers and force native born citizens out of work. The counter-argument is that, in the long-run, mass refugee waves offer a complementary approach to low-wage vocational opportunities not often sought by native-born citizens and can spur entrepreneurial growth and positively contribute to fields through research and development. Many who posit such economic development see short-run wage drops and unemployment spikes as necessary evils on the path to economic growth.

In a Dec. 14 study done by Diana Furchtgott-Roth at the Manhattan Institute, the issue is framed in regard to how a balance of both low and highly-skilled refugees can pose direct economic benefits over time. She finds that this complementary approach provides great balance to a western economy:

“The most important way immigrants benefit the U.S. economy, according to academic literature, is their possession of different skills and job preferences from those displayed by native-born Americans . . . immigrants complement rather than substitute for native-born workers, with capital moving accordingly to maximize available labor.”

These ideas are furthered in a Sept. 2015 Brookings Institute article by Massimiliano Cali and Samia Sekkarie. Their work points to the surprising economic growth seen in nations such as Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan who have taken in huge numbers of refugees in proportion to their population size. Jordan has seen a near 2.5 percent GDP increase, while Lebanese exports have increased by 1.5 percent after the refugee surge. Refugees in the Turkish labor sector have additionally “generated more formal non-agricultural jobs and an increase in average wages for Turkish workers.”

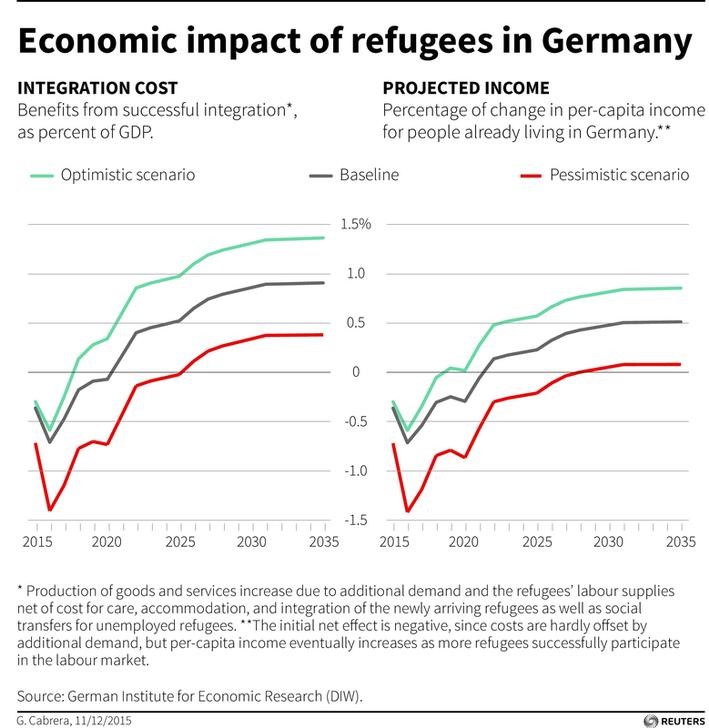

It may, however, prove instructive to see how refugees have assimilated economically in a comparable western nation: Germany. In a study done by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, it was found that there exists a stark divide in how to handle the refugee problem: those who see it as an economic blessing and those who see it as a tax-payer’s burden. The blessing camp contends:

“The country’s aging society is in urgent need of young workers to make up for millions of retiring Germans. Around one third of the 1 million migrants and refugees who entered Germany in 2015 are under the age of 25 and their labor will help maintain the generous pension and benefits system Germans hold dear. The integration of refugees, the argument goes, may be costly for Germany in the short run, but refugees’ contributions will outweigh these start-up costs after a few years, leaving the German economy better off.”

An Oct. 2015 Bruegel article cited that while German taxpayers may see initial expenses in the short-run, “extra-spending does not vanish in a black hole, but is actually stimulating internal demand in Germany,” and should eventually result in a budget surplus.

In an interview with Professor Monshipouri, he explained how when refugees are pushed out of their nation without easily transferrable assets, they can provide a boon in wage-labor: “They can be used as a large pool of labor, especially in industrially based economies where you need cheap labor. Germans are embracing the refugees because they know that they need to fill jobs.”

There additionally exists evidence that Syrian refugees are more skilled and educated than previously thought. In the same study done by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, it was cited that: “Nearly nine out of ten Syrians arriving in Greece report high levels of education, with 43 percent holding a university degree, and another 43 percent a high school diploma.”

However, if we look historically at refugee waves from other Middle Eastern and North African countries we can see that certain evidence suggests this complementary balance of highly-skilled refugees and low-wage laborers does not always pan out to economic growth. In a Jan. 2016 Economist article, an IMF study is cited that refugees struggle to find their financial footing — even 20 years down the line:

“A new paper from the IMF uses existing immigrants to Europe from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iran, Iraq, Somalia, Syria and the former Yugoslavia as proxies for the latest wave of refugees, since most of them come from those countries. Relative to other immigrants, people from those countries who have been in Europe for less than six years are 17 percentage points more likely to rely on benefits as their main source of income and 15 percentage points less likely to be employed, even after controlling for things like age, education and gender.”

While such findings point to a burden on taxpayers imposed by refugees, skill-oriented inclusion plans, such as the H-1B program, could ostensibly help these waves of refugees find their footing financially.

However, in regard to long-term growth, the issue deviates from axioms about complementary employment practices. Refugees, particularly such as the current wave we see from Syria, come with little to no financial support and skill sets that are in large part regionally and linguistically specific. Syrian refugees are thus left destitute and without easy transferable resources to western economies. In essence: it may take time for their contribution to the state to exceed the financial burden.

In the same Jan. 2016 Economist article, the author underscores such an argument through case examples from refugee waves in Australia: “Barriers suggest that it will be awhile before refugees pay more in tax than they receive in state support. A study of Australian refugees found that they paid less tax than they received in benefits for their first 15-20 years of residency.”

Waiting such long periods of time to see economic growth could act as a deterrent to any western economy. It may take a new and rejuvenated approach to this refugee question to create a more decisively positive plan. What remains germane is that Syrian refugees, and refugees of all conditions, can offer viable economic benefits to host nations if cultivated with the right social and assimilatory factors. However, if approached incorrectly, host nations may simply continue to disenfranchise and marginalize these refugee groups.

In the same Sustainable Security article, Monshipouri states that inflaming corrosive, sectarian thought in western nations may only make matters worse in preventing ISIL infiltration: “Many studies have shown that the absence of a protective and enabling environment is likely to render more young people vulnerable to racist ideologies and movements and ease the process of their recruitment into the ranks of radical groups like the Islamic State or al-Qaeda.”

Monshipouri continued in an interview that there are key social factors that can aid assimilation efforts and ultimately, economic benefits: “The key [to inclusivity] depends on the extent to which they can be socially integrated. How do you actually draw on their talents but at the same time socially integrate them into society? 1. Teach them the language. 2. [Provide] rights to education. 3. Provide vocational training . . . This is a good investment because the dividends are very high.”

As we approach Nov. 8., as partisan rhetoric and nationalistic sentiment is stirred, this discussion may seem less and less feasible. Yet, a candid debate in regard to economic growth through refugee assimilation remains an objective approach to this argument without unfounded generalizations of Islamophobic sentiment.

Aziz Dyab wants to be an astronaut. Like many of his native people, he sees a future not dictated by Russian cruise missiles, a corrupt regime and little to no financial stability.

While the polemic swirls around statistically unlikely terrorist linkages we lose sight of how this refugee wave, comprised of hopeful astronauts and shopkeepers alike, can provide gradual economic growth. However, if states don’t provide tested assimilatory programs, refugees might never fully realize their vocational potential and continue to burden the state.

Our national conversation has avoided confronting the reality of this dire situation: the tangible economic ramifications of assimilating millions of desperate refugees. As long as stories such as Aziz’s are pushed to the background to make room for darker narratives, a conversation of substance will continue to elude us.

Featured Image Source: NBC News

One Comment