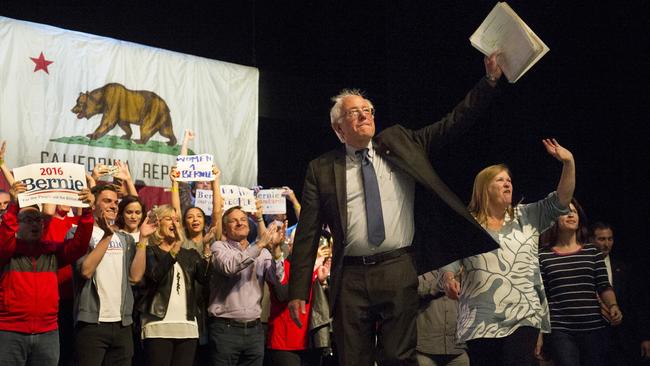

Senator Sanders’ rallies, like this one in Oakland, CA drew thousands of enthusiastic supporters. (Getty)

Despite the hype, California didn’t swing for Bernie on June 7, 2016. While national polls predominantly aligned with Clinton, a Sanders victory was still a real possibility leading up to the California primary, especially coming on the heels of a well-won Midwest campaign which included an upset in Michigan. While Clinton already had the majority of delegates, the Sanders campaign strategized that winning California by a large margin would persuade a substantial amount of superdelegates to change their pledges in order to give Sanders a majority vote at the Democratic National Convention and thus clinch the nomination. As the primary approached, this strategy seemed plausible. The latest polls conducted by the American Research Group, CBS/YouGov, and the Field Center all placed Sanders well within the 3% margin of error; some, such as the NBC/WSJ/Marist Poll had Sanders leading Clinton by one point. Senator Sanders had also been campaigning heavily in some of California’s most liberal districts, such as Alameda County. His support in the Bay Area alone were so overwhelming that if the nine-county area were its own state, it would have ranked third on most donations per capita, preceded only by Vermont (Sanders’ home state) and Washington D.C. If he were to win, he would have to carry long-time liberal strongholds such as San Francisco County and other coastal population centers. However, by the time the dust cleared and the votes were tallied Clinton had won by a sizable margin of over 7 points. Moreover, she had won California’s most liberal counties including Alameda, San Francisco and Marin. Many expected a Sanders loss, but few could predict such an overwhelming Clinton victory. Why were the results of the California primary so different from the projected outcome?

Since its inception, the Sanders campaign persistently noted that the key to its success lay in large voter turnout. To access this, a major tenet of the Sanders campaign was to increase voter registration of non-voting populations, such as youth, which could then translate to more votes on June 7. According to California Secretary of State Alex Padilla, over 2 million new voters registered for the 2016 primary with almost 650,000 new voters were registered just between March 28 and April 8. Of those new voters, over 75% were Democrats. Despite this, only 47.7% of the state’s registered voters cast their ballot; Clinton had a long-standing coalition of supporters, leading Sanders by a two-to-one margin among middle aged voters and polling 57% to 36% among African-Americans, but it was California’s large Latino population which swung hard for the former Secretary. Clinton won all twelve of California’s supermajority Latino districts. Additionally, these districts are some of the most populous in California. For example, Los Angeles County is over 70% Latino, and rallied to Clinton with over 60% of votes in her favor. Statewide, Clinton’s ability to pick up Latino votes ultimately worked as a major blow against Sanders, as Latinos in California total almost 15 million, or 39% of the state’s population.

While Sanders push to register more voters seemed to succeed, a rise in voter registration does not necessarily correlate to a rise in support for Sanders. Popular rhetoric during the primary assumed many of those 2 million new voters reflected the passion of Sanders supporters preparing to hit the polls. But, as Darry Sragow, a veteran Democratic strategist and political analyst and member of the Public Policy Division of Dentons—an international law firm—put it, “To suggest a surge is only because of passion for Sanders—and there is passion—and overlook the fact that the notion of a Trump presidency is an awful thought to a lot of Democrats misses the point.” In other words, these voters could have been equally motivated against Trump and for Clinton, not necessarily in support of Sanders.

Additionally, part of Sanders’ draw was his ability to market himself as a fresh voice on the national campaign stage. While this meant he was able to attract younger voters en masse, older voters were more apprehensive about backing his campaign. This was especially evident with the influential Latino vote in California; younger Latino voters under fifty supported Sanders 58% to Clinton’s 31%, yet voters over fifty supported Clinton by 69% to Sanders 16%. Many older voters respect Clinton as a stalwart of the Democratic party, and chose to back the candidate whom they felt was politically tested and ready to go up against Trump in the national election. Additionally, Latino youth support for Sanders does not correlate to Latino youth voting turnout for Sanders, as the youth voting demographic, regardless of ethnicity, has the most unreliable turnout rates in the state.

While over 70% of voters aged 18-29 favored Sanders in the California primary, only 10% of voters aged 35 and under turned in their ballots. The youth vote in California has long been predictably underwhelming, and it was dismal turnouts like these which contributed to the under-thirty-five demographic’s “all bark and no bite” political image. In fact, a 2015 study conducted by the nonprofit research firm CA Fwd found that in the 2014 elections, just 8.4% of youth ages 18-24 cast a ballot. The most accepted hypothesis for low youth voter turnout is that younger voters have less at stake, as they have yet to buy into state and federal programs at the extent to which older voters do. Young voters, for example, often do not reap the benefits of social security or health care, and more often than not, do not own houses. As a result, they are less concerned about ballot measures and other issues such as property taxes and thus have less of an incentive to turn out to the polls when programs and issues like these are at stake. The Sanders campaign was dependent upon the mobilization of previously non-voting populations. While Bernie Sanders may have succeeded in getting thousands of youth focused on politics and registered to vote, not enough of the younger generation followed through with the second half of the strategy, turning in ballots.

Moreover, while most polls which showed Sanders tied or trailing Clinton within the margin of error obtained their data without including the unusually high propensity of mail in, absentee and early vote ballots used during the 2016 primary. Many Asian-Americans and Latinos (which together make up roughly 50% of California’s population) historically vote by using mail-in-ballots (in 2012, 39% and 58% respectively). For the primary, this meant Clinton had a relatively unreported 400,0000-vote lead well before June 7. Many polling centers failed to take this into account and derived their numbers from expected turnout at local polling centers, ignoring a large portion of California voters. Moreover, mail-in voters tend to be older. Over 50% of voters 54-63 and 70% of voters 64 and older use mail-in-ballots. Both demographics (as noted previously) voted overwhelmingly for Clinton. Additionally, according to a 2012 study done at UC Davis, the voting group with the highest propensity of rejected vote by mail ballots happened to be the 18-24 year-old demographic, whose ballots were rejected for a variety of reasons, including missing signatures and missed deadlines.

Indeed, much controversy sprang up from Sanders supporters post-election following accusations of election fraud, as it took the State an additional month to tally all mail-in votes. However, to the chagrin of the many tin-foil-hat theorists, this was to be expected, as there were over 2.5 million mail-in votes in total (including the 400,000 previously mentioned). Votes are counted not by State Secretary Alex Padilla, but by the individual counties that report the votes. These individual counties operate on their own time schedule, employing differing numbers of employees who all have to certify varying numbers of ballots. With each of California’s 58 counties having to certify thousands of ballots, many of these coming from mail ballots, newly registered voters or votes cast at local polling places, it is reasonable that vote counting would take longer than expected. Unfortunately, these mail-in ballots did not spell success for the Sanders campaign as many of them came from counties in which Clinton had already won. Los Angeles County, for example, had over 340,000 mail-in-ballots, yet this was a county which had already voted Clinton by a margin of over 10%. Even as vote counting was being finished, Clinton had already won many counties by a high enough margin such that the mail-in-ballots made no difference.

Finally, it seemed that Sanders’ old claim of “when voter turnout is high, we win” seems to have been proven mostly false throughout the 2016 election. Across the campaign trail, Sanders consistently won caucuses, where voter turnout is low, while losing large primaries like New York and California. Primaries are often determined by the respective state’s large population centers; in California, these are Los Angeles County, San Diego County and the Bay Area. All three of these areas swung for Clinton (even Alameda County, which contains both Berkeley and Oakland, supported Clinton by a 5 point difference). Urban areas tend to be more racially diverse, with high populations of middle class Whites, Latinos, and African Americans, all key members of the Clinton block. This is not to say that Bernie’s coalition is not diverse; it has the potential (depending upon his future political plans) to transform into the most diverse political movement in American history, but that was not the case in California. Clinton’s ability to rely on a large and loyal voting bloc that encompasses much of the baby boomer generation, a generation which outvoted youth by over six-to-one, was what gave her the edge in California. Clinton’s ability to form a coalition of loyal voters is mirrored nationally. Black voters (which played a large part in Clinton’s Super Tuesday victory in the South) shared similar voting habits in California and helped her to carry many of California’s more urban constituencies. Latinos in California overwhelmingly supported her as did those in Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas, three states that she also won with decisive numbers.

In many ways, the California Democratic Primary was a microcosm of the 2016 primary presidential race. Sanders mounted a hearty challenge to the establishment-favored Clinton. He successfully sparked the interests of America’s younger generations in politics, motivating more people to register to vote, especially young people, than ever before. Perhaps members of polling organizations and the various news media outlets for once began to “feel the Bern” themselves, which resulted in them predicting an unreasonably close race in California. Many theorize that Sanders may have turned a new page on how campaigns, at least Democratic campaigns, are to be run in the future. While that may bode well for those who crave a “political revolution” of some sort, leaders like Clinton, as well as her campaigns, are here to stay, at least for this race.

Featured Image Source: Getty Images

Be First to Comment