When the Colombian government’s peace agreement with the Farc (The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), to end the 52-year war was rejected, many were shocked. After all, it was turned down by an incredibly thin margin, about 0.2%. However, that thin margin highlights what a fragile peace it would have been. For half of voters to be upset with either outcome sends a strong message that those sitting at the table need to construct a more complex peace, taking into account all who have been affected by the war, and in what ways.

The Farc is a Marxist-Leninist group that has long sought, among other things, land reform in response to Colombia’s profoundly unequal land ownership, which has historically been concentrated within a minority of elites. The group became embroiled in the drug trade in the 1970s as method of funding and remains involved. They have been fighting the government since Colombian security forces attacked their still loosely-organized group on May 27th, 1964, making this the longest-running conflict in the western hemisphere. The Farc have been accused of kidnapping children to serve as soldiers, a charge that they deny, although they admit having what they say are willing youth serving as soldiers. Many Colombians are bitterly angry with the Farc because of its negative impact: forced youth conscription, extensive kidnapping-for-ransom, and thousands of civilians deaths due to landmine explosions and other violence. The war has claimed approximately 260,000 lives. Consequently, the terms of the peace deal were deemed by some to be too lenient on the rebels, particularly by sparing them jail time for war crimes and giving them 10 seats in Colombia’s 268-member congress (for two terms, 5 each in the house and the senate). Despite this concession only granting the group about 3% of congress, it was a main source of outrage for those supporting a “No” vote. The deal required the Farc to give up their weapons to the UN within 180 days of the agreement. President Juan Manuel Santos also committed to investing in rural infrastructure, a win for the areas the Farc has held power in and their ideology of fairness for the farming class.

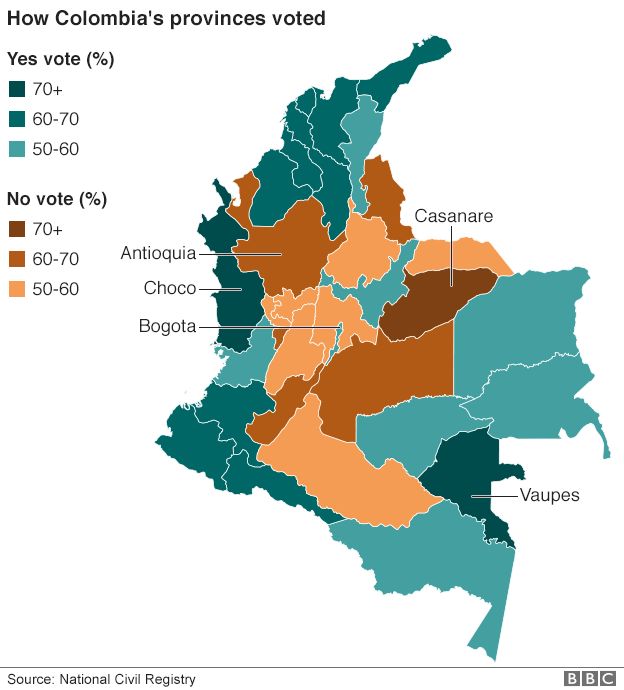

Alvaro Uribe, Colombia’s former President and a current senator, led the opposition against the deal, which was the result of four years of negotiations in Havana, Cuba. As a conservative, Uribe has cautioned against the leftist swing allowing the Farc into the political process could bring. In some ways, the controversy surrounding the referendum became tied to larger political ideology, with the referendum vote showing striking similarities to the map of the 2012 election in which current President Santos was elected. Santos spearheaded the deal and has spent much of his tenure focusing on its success. Uribe himself lost his father to the Farc, and is supported by many of the landowners that are its nemeses. While foot soldiers would have amnesty and access to reintegration programs, perpetrators of war crimes would have to admit to them in a special tribunal, but would then be sentenced to community service and restricted movements for up to eight years. This was widely reported as “amnesty for war crimes”, which is not technically correct. There was much exaggeration and disinformation surrounding the 297-page accord that few members of the public actually read. Importantly, the rural areas that have borne the brunt of the war’s violence and disruption overwhelmingly voted “Yes”, showing a strong desire to end the war.

Although the Farc signed the deal, smaller left-wing rebel groups such as the National Liberation Army (the ELN) are not a part of the agreement, in addition to right-wing militias that were formed by landowners to defend against the Farc. This led many to be concerned about the state of Colombia post-deal even before the voter rejection. Without these groups at the table, Colombia leaves a vacuum by taking the Farc out of the rebel strategy and illicit drug trade. This could allow groups such as the ELN to grow in power and set off another era of the conflict. Colombia has been seeking to negotiate with ELN, and the beginning of formal talks was recently suspended due to the ELN failing to release a major hostage. The country cannot afford for the tentative beginning of these talks to fall apart, and the Santos administration should agree to meet, setting in clear terms that the hostage in question, a former congressman, will be released in good faith following the first meeting. They cannot allow this skirmish to prevent a formal bargaining, as it is essential that ELN be onboard for the construction of peace to be effective and lasting.

Many Colombians have expressed their outrage at the lack of justice for the Farc’s victims as their reason for voting “no.” If Santos believes that amnesty and lack of jail time were prerequisites for ending the war, he must find another way for the Farc to reconstruct the damage done. Obviously the restorative justice proposed does not feel like proper repayment to many Colombians, and they will need to be asked what else besides lengthy jail terms might calm their objections. Uribe, for his part, must be willing to accept a peace that works, and not use his political clout to exploit the wounds of Colombians. They will not be better off should the seeking of peace fall apart, allowing the war to continue. The wishes of those living in war zones who have known the most hardship from the conflict must be respected, since they will also have to most to lose in the event of a failed peace. Finally, the Colombian people must be properly informed, with leaders refraining from hyperbole and clearly relaying the actual details of future decisions. This may produce more engagement, since the referendum had only a 37.44% turnout. The rejection of the peace deal, if handled skillfully, may be an opportunity to deliver an agreement that will change the course of Colombia’s reality, rather than ushering in a new era of its conflict.

Featured Image Source: BBC