The Growing Divide in Chinese-African Relations

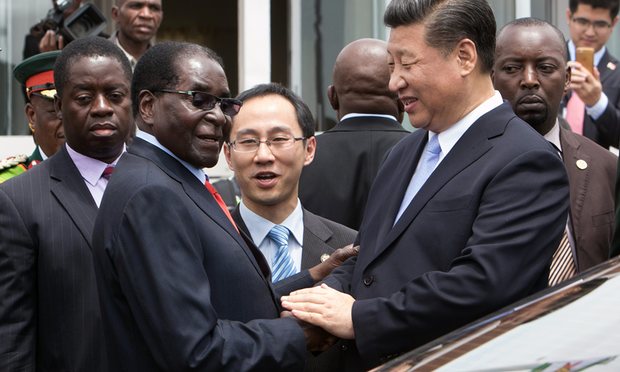

In December 2015, President Xi Jinping was declaring Zimbabwe to be China’s “all-weather friend.” Less than a year later, President Mugabe of Zimbabwe was accusing the Chinese of undermining his nation’s economy and “taking advantage” of Zimbabwe’s women. This seemingly rapid transition in relations might appear to be unexpected, but closer observation shows that this is not at all surprising.

It has been a decade since President Mugabe turned to East Asia to lift Zimbabwe out of its economic death spiral. Although his administration never officially outlined policies that favored economic ties with the East rather than Western financial institutions, Zimbabwe, like many other African nations, has pursued economic policies that draw it closer to the non-interventionist East.

Africa has had difficulties attracting foreign investment in the past, calling into question the prevailing thought that capital flows downhill. Human capital and infrastructure issues aside, African economies have the potential to yield high returns on investments due to the abundance of labour and natural resources, but African governments have become notorious for setting up administrative barriers that disincentivize investors. Corruption, failure to uphold property rights, and endless bureaucratic red tape have all deterred potential investors. Rampant human rights abuses by leaders such as President Mugabe and a disregard for democratic principles have further increased tensions between Western investors and African governments. Organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank have pushed neoliberal economic agendas along with their investments, requiring nations to make structural adjustments in order to receive investments, including the privatization of certain industries, market liberalization and deregulation. These adjustments have left African countries poorer in some cases, as foreign competition and the pressure to export to pay off debts has driven resources away from domestic investment in health care, education and other vital sectors.

As African leaders grew tired of being micromanaged by the West, they increasingly turned to Eastern investors, particularly China, which quickly became Africa’s largest trading partner with $220 billion dollars in trade. China turns a blind-eye to human rights abuses and political corruption on the continent and in exchange gets to flood African markets with cheap manufactured products and capitalize on the continent’s bountiful natural resources. In turn, this allows African governments to govern as they wish while maintaining strong economic ties with the world’s second-largest economy.

Under the surface however, this symbiotic relationship is not as friendly as it seems. Chinese investments in infrastructure and natural resource extraction have shackled many African countries with debt that they will have to repay for decades to come. In Zimbabwe, as well as other countries that partner with China, domestic businesses are struggling to compete with the influx of cheap Chinese goods. The new jobs created by Chinese investments are skewed to China’s benefit, with Chinese workers making six times as much as their local counterparts for similar jobs. But the problems do not stop there.

Chinese investors seem to have no regard for pollution laws and workers’ safety, flagrantly violating the law. Workers in Zimbabwe have reported that the Chinese companies they work for fail to provide them with overtime pay or safety equipment. In 2008, Chinese owners of mines in Zimbabwe’s Marange diamond fields were accused of conspiring with local police as well as their privately employed security guards to forcibly remove unlicensed local miners, resulting in the deaths of up to 200 people according to human rights groups.

Workers and human rights organizations reported for years that China’s increased involvement in African economies is leading to more human rights abuses and economic inequality, but it is not until recently that high-ranking officials have begun to express these concerns. Nigeria’s former central bank governor, Lamido Sanusi, pointed out the neo-imperialist nature of Chinese-African trade relations, in which China extracts raw materials from Africa and uses Africa’s markets to sell its manufactured goods. Even President Mugabe is finally beginning to see the downsides of a partnership with China. He decided to unilaterally nationalize several mining firms in March of this year, two of which were run by Chinese owners, because he believed that those companies were robbing Zimbabwe of its wealth — $15 billion worth of diamonds, to be exact.

But this rift in Chinese-African relations is going to hurt African economies much more than it will hurt China’s. While the Chinese have created their fair share of economic problems on the continent, African governments have also contributed to this fraying relationship by subjecting Chinese investors to the bad governance that has plagued African economies and deterred investment for decades. By not honoring property rights and contracts, as Mugabe’s nationalization of the mines shows, African leaders are cementing the idea that investments in their respective countries are risky. But these administrative obstacles existed long before Chinese investment began, and do not fully explain the deteriorating relationship between Chinese investors and workers and African officials and residents.

This risk could potentially drive Chinese investment away for good. China has similar investments in many other emerging markets around the world, and will simply move on to a more profitable continent to extract resources — President Xi Jinping has already pledged to invest $250 billion in Latin America. While China is Africa’s largest trading partner, it is far behind other nations when it comes to foreign direct investment (FDI). Britain and the United States are still Africa’s largest partners in terms of FDI. However, Chinese investment in Africa is still strong, with a recent shift towards investments in the service sector as well in manufacturing, which is more likely to increase African competitiveness and growth than the extraction of natural resources.

That being said, Chinese investors are in no way limiting their investments to the African continent and will invest wherever they believe they will receive the highest returns. If African governments continue to put up red tape or nationalize businesses, the investors will go elsewhere. As commodity prices fall and foreign competition makes it nearly impossible for local business to compete, African governments will have to change gears if they want to avoid an economic crisis. African leaders do not have to necessarily turn to the West in response, but continuing to look East while ignoring problems at home will only continue this cycle of economic abuse. Without effective change and reform, present and future relations with foreign investors will leave Africans as secondary benefactors in their own economies.

Featured Image: Jekesai Njikizana/Getty Images

Be First to Comment