Austin, Indiana, in many ways, is remarkably unremarkable.

A small, mostly white, non-Hispanic population nestled in the center of the state, Austin may be your quintessential small-midwestern town. Family-owned ranches interspersed with mobile homes and yard signs that read, “”No Trespassing,” “Private Property,” “Keep Out.”

A lackluster main street and struggling small businesses typify the Austin experience. Median household income is down $15,000 compared to the Indiana average, as found by a May 2016 Digg piece. The town is isolated, derelict.

Yet, in recent months, Austin has made international headlines. Austin has become the latest victim of a sweeping, nation-wide epidemic. 200 of its roughly 4,000 inhabitants have been diagnosed with HIV.

The epidemic has affected small-towns from Massachusetts to West Virginia. A 2014 article in The Guardian details the spread of this epidemic across the United States, beginning in the Appalachian region of West Virginia: “In central Appalachia, as in many parts of the country, the prescription painkiller epidemic also fuelled the influx of a cheap, alternative opioid: heroin… In all, West Virginia’s overdose death rate rose nearly eightfold between 1999 and 2014.”

2014 may have been the apex of the now decade-long heroin epidemic weaving its way across the U.S. The Center for Disease Control reports “More people died from drug overdoses in 2014 than in any year on record. The majority of drug overdose deaths (more than six out of ten) involve an opioid. And since 1999, the number of overdose deaths involving opioids (including prescription opioid pain relievers and heroin) nearly quadrupled.”

Heroin is an overwhelmingly white issue. Between 2011-2013, white communities experienced a 114% increase in usage, while black communities experienced little to none. 90% of first-time users are now white, and a majority are middle-class or wealthy.

The spread of heroin to small, suburban communities has altered police practices. A June 2016 NBC News article cites that the heroin epidemic has triggered a revolution of sorts in how police deal with addicts in small communities: “Across the country, police and prosecutors are embracing similar programs that divert nonviolent offenders away from jail and into programs to help beat their addictions. This development has been driven by a growing acknowledgment that old methods of locking up addicts, which may have cut crime in the short term, did little to stem the flow of drugs into the country — or reduce the demand for them.”

This shift from increased policing to compassionate reform marks an overarching trend in how policies are now designed to meet drug addicts: with rehabilitation rather than incarceration.

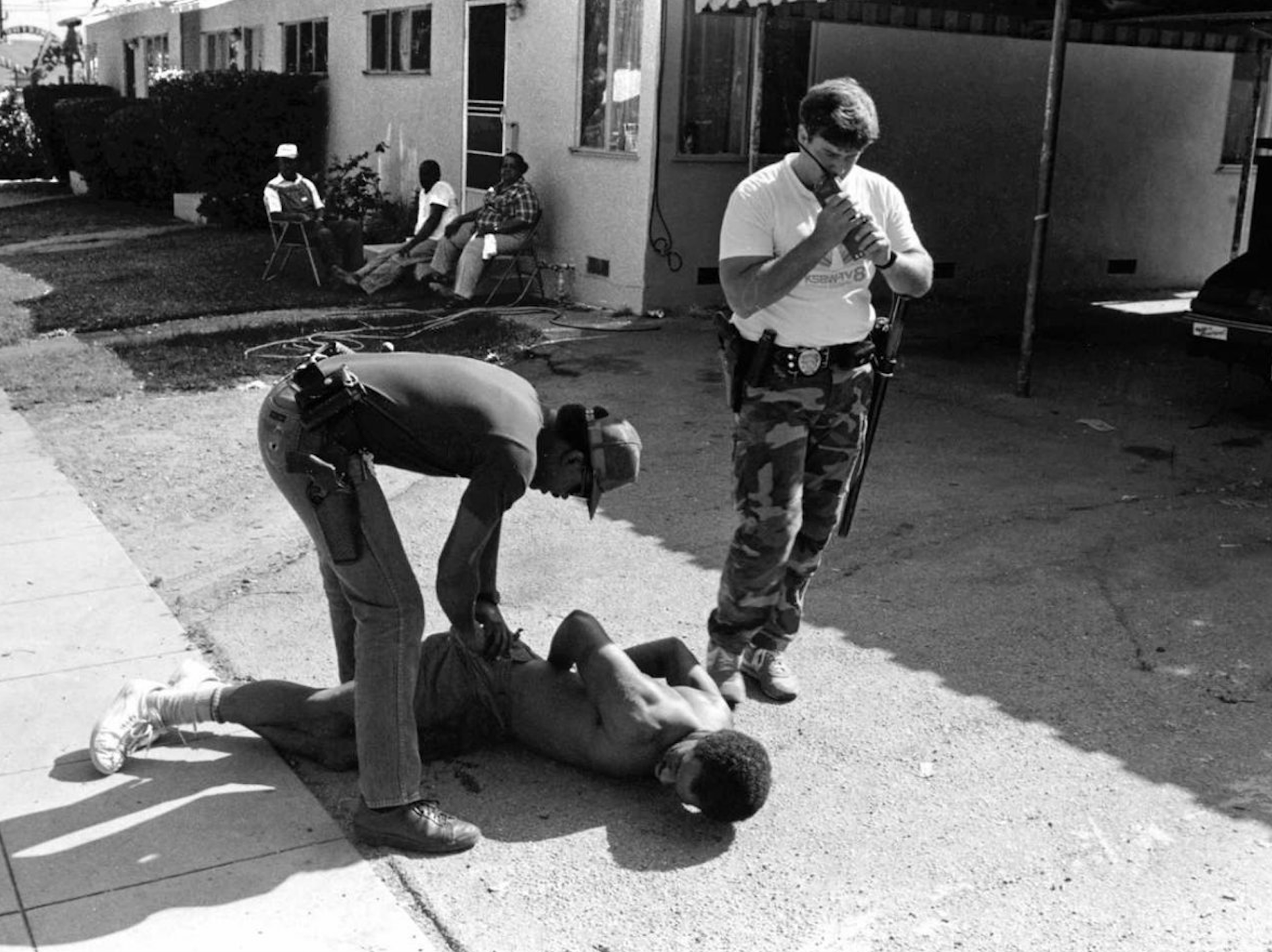

This empathetic response to the heroin epidemic marks a stark policy reversal to the police militancy that met the last American drug epidemic, the crack-cocaine epidemic of the 1980s.

Crack-cocaine first emerged in United States markets in the early 1980s, arriving primarily from Columbia and other Latin-American countries. This epidemic was primarily tied to inner-city communities comprised of ethnic minorities, predominantly African Americans. Many argue the epidemic spread in inner-cities due to the affordability of the drug, compared to powdered-cocaine which is generally more expensive. The Journal of Psychoactive Drugs in 1999 found that the influx of crack to inner-cities prompted waves of violence and heightened incarcerative stringency.

“In 1986 and 1988, Congress passed anti-drug abuse acts that mandated long prison terms for crack-related crimes and dedicated funding for new drug enforcement efforts… What began with $2 billion of federal money snowballed into $16 billion by 1998”

In a 2015 Atlantic piece, writer Andrew Cohen explained that the mandatory-minimum sentences instituted to punish users of crack cocaine disproportionately affected African American communities who could not afford the powdered, more expensive version of the drug.

A 2006 Harvard University study of the effects of crack-cocaine prevalence in the 1980s highlighted the violence in minority communities emblematic of the racial divide:

“We find that the rise in crack from 1984-1989 is associated with a doubling of homicide victimizations of Black males aged 14-17, a 30 percent increase for Black males aged 18-24, and a 10 percent increase for Black males 25 and over, and thus accounts for much of the observed variation in homicide rates over this time period.”

This data points to the stereotype that was born from the heightened violence: inner city communities, composed of many African Americans and minorities, are inherently violent and as Ekow Yankah of the New York Times puts it, “an indistinguishable and unsympathetic mess.” In Yankah’s Feb. 2016 article, he placed this militant stereotype in the spotlight, underscoring just how systemic the perpetuation of crack culture has become for black communities:

“The plight of Black America was evidence of its collective moral failure — of welfare mothers and rock-slinging thugs — and a reason to cut off all help. Blacks would just have to pull themselves out of the crack epidemic. Until then, the only answer lay in cordoning off the wreckage with militarized policing.”

Yankah, too, underscores the idea that politicians and media alike have responded so disproportionately from the crack to heroin epidemics due to the constituencies they seek to protect: white communities.

“The national attitude toward drug addiction [heroin] is utterly different. Even Republican presidential candidates are eschewing the perennial tough-on-drugs speeches and opening up about struggles within their own families. More important, police chiefs in the cities most affected by heroin are responding not by invoking military metaphors, weapons and tactics but by ensuring that police officers save lives and get people into rehab.”

This new understanding of addiction has even spawned legislative activity. President Obama signed into law on July 22, 2016 the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA) with the intent of advancing: “a large number of treatment and prevention measures intended to reduce prescription opioid and heroin misuse, including evidence-based interventions for the treatment of opioid and heroin addiction and prevention of overdose deaths.”

The media has, too, steeped the heroin epidemic in a victim culture of compassionate, narrative reporting while the crack epidemic of the 1980s was steeped in militancy and violence.

Stories such as a 2014 Rolling Stone piece, “The New Face of Heroin,” have sought to humanize the epidemic in many suburban northeastern communities: “Shumlin’s core initiatives – expanding treatment programs and funneling addicts into them instead of prison – are already being embraced as models for the rest of the country.”

This conversation of empathy that has predominated the comparatively sparse coverage of the epidemic points to a greater question: Why is that we ascribe a victim connotation to the white communities affected by heroin? Why is their crisis met with rehabilitation and treatment converse to the vitriol that met black communities?

The answer is not definitive. Local politicians may be looking to protect their largely white constituencies in rural American towns, as was stated in the same 2015 Atlantic piece: “Heroin use has changed from an inner-city, minority-centered problem to one that has a more widespread geographical distribution, involving primarily white men and women in their late 20s living outside of large urban areas.”

An argument that has been used in the past to justify historically stringent sentencing limits for crack cocaine users is that crack cocaine users are inherently more violent. A 2010 study done by The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse explored how crack-cocaine users may be seen as more violent in comparison to powdered cocaine:

“Another reason there may be an association between crack cocaine usage and greater violence may be a function of cost. Crack cocaine “rocks” or pellets are less costly in relative terms, and thus potentially greater quantities can be ingested for less money in a shorter amount of time and with greater intensity of effect than powdered cocaine. This may increase the likelihood of rage or paranoia-induced aggression among crack cocaine users compared to powdered cocaine users.”

Crack cocaine users are additionally more susceptible to join street gangs, as was stated by a Department of Justice article in 1999: “Several studies document considerable youth and adult gang involvement in the drug trade after the cocaine epidemic began around 1985”

Statistics that emerged from these at-risk communities helped to further the growing stereotype that minority crack users are far more susceptible to joining neighborhood gangs and lashing out violently to fund their addictions.

Heroin users, however, do not suffer from the same stigmas of violent behavior. This may have informed the severe police response and stringent mandatory-minimums that plagued minority communities suffering from crack abuse in the 1980s. However, after the passage of the 20120 Fair Sentencing Act, we have seen the severe sentencing for crack cocaine offenders dissipate over time.

What remains important in comparing epidemics is not to dismiss the progressive policies that now value treatment over prison time, but to address how progressive policies have not been evenly disseminated to all communities and minority groups.

Austin, Indiana is not anomalous. Nor is it isolated or unique. Austin, Indiana is a link in the growing chain of white, suburban communities being ravaged by opiate addiction. Instead of heightened police presence, a culture of empathy and compassionate reform has met these communities – a response that may have benefited afflicted minority communities in the 1980s. In his New York Times piece, Yankah may state it most succinctly:

“It is hard to describe the bittersweet sting that many African-Americans feel witnessing this national embrace of addicts. It is heartening to see the eclipse of the generations-long failed war on drugs. But black Americans are also knowingly weary and embittered by the absence of such enlightened thinking when those in our own families were similarly wounded.”

The gulf has been made clear. The disparities, entrenched.

Featured Image Source: The New York Times

Be First to Comment