The Problem with Medical Price Gouging

At 76 years old, Jacqueline Racener was diagnosed with leukemia. Once diagnosed, her doctor prescribed Imbruvica, a drug that had a very high chance of helping Ms. Racener beat her disease. Unfortunately, this Imbruvica would have cost Ms. Racener $8,000 a year – even though Medicaid was picking up the majority of the cost for the drug. Unfortunately, she could not afford this high expense and decided against filling her prescription for this life saving drug.

But Ms. Racener is not the only one suffering from inflated drug prices. The recent price increases in HIV medication and Epipen have brought this issue into the national spotlight. Yet so far, very little has been done to combat this epidemic of increases. The United States government has the ability to ensure that companies cannot inflate the price of drugs, such as price control and increasing imports from other nations. However, intense lobbying by Big Pharma adds an additional obstacle to this legislation.

The price of medicine can make a large and tangible impact on people’s lives. According to a 2013 report from the Center for Disease Control, about eight percent of adults did not take prescriptions that were prescribed to them in order to save money. This number jumps up to 14 percent among those who do not have insurance. This means that approximately ten percent of people in the United States –about 32 million people – have not taken medication that their doctor prescribed to them because they felt that it was too expensive. Those who live below the poverty line are even more likely to skip medication, showing the impact that socio-economic status can have on access to medication. The report went on to say: “This cost-saving strategy may result in poorer health status and increased emergency room use and hospitalizations” showing the negative impacts that skipping medication can bring.

One way to address inflated prices is through government imposed price controls. The government can set a limit to how high the price of different drugs can be to keep them affordable. The government already does this for some people. Medication for people who have Medicaid is cheaper than markets dictate because the government has the power to bargain with the companies to set the price. In fact, medication bought using Medicaid is about 20 percent cheaper than the price paid by the average buyer. Other US departments, such as the Veterans Health Administration, require companies to give them specific discounts on medication. This shows that the government does have the power to negotiate price down with drug companies, leading some to wonder why this should not be implemented on a wider scale.

In 2016, some citizens of California attempted to formally institute price controls with Proposition 61. This ballot measure would have made it so no state agency would buy drugs at a cost higher than what the Veterans Health Administration pays for the same drugs. This measure would not have directly impacted the price that all individuals pay for medication, but by lowering the price that state agencies pay the framers of the initiative hoped to ultimately lower drug prices across the state. One of the proponents of the measure, Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, felt that this measure would not only lead to lower drug prices in California, but could start a nationwide movement against price gouging.

And yet Prop 61 did not pass – over seven million people voted against the measure. Opponents worried that this measure could raise the price of medicine. Some worried that having prices based on the price that the VA pays for drugs could incentives drug companies to charge the VA more, leading to higher drug costs for veterans. Some opponents of the measure, like US Representative Tom McClintock of California, believe that it “will likely increase overall drug costs as the market adapts and create drug shortages along the way. Price controls always sound good in theory – but in practice they always create shortages of whatever commodity is being controlled.” The fact that a traditionally progressive state like California did not manage to pass this measure makes it doubtful that a measure like this would be passed on the national level anytime soon.

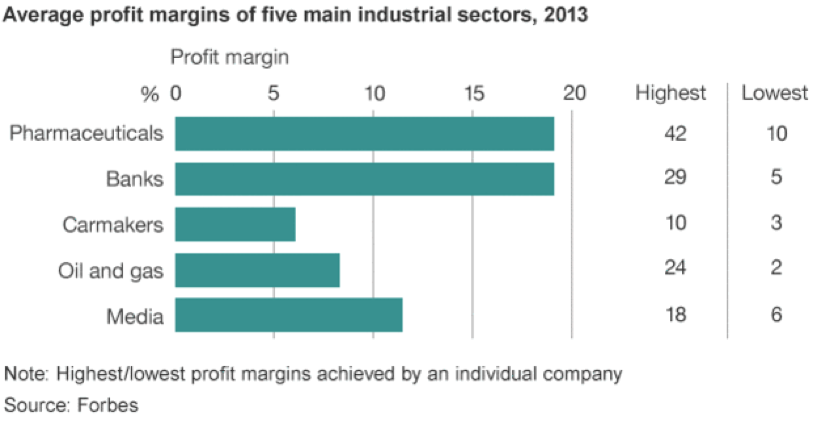

There are also more general reasons why many oppose price control on prescription drugs. Some worry that if drug prices were to be lowered by the government, pharmaceutical companies would have less money to spend on research and development, decreasing medical innovation. This is a clear drawback of price decreases – the research that these companies fund can provide for lifesaving treatments. Some see this as an empty threat meant to keep drug prices high. In 2014, Pfizer, the world’s biggest pharmaceutical company, made a record high forty-two percent profit margin. With companies making this much profit, it is difficult to believe that any loss of profit would have a major impact on their ability to do new research.

Yet price ceilings are not the only way to bring down drug prices. Many proponents of price reform, such as Bernie Sanders, feel that allowing drugs to be imported from other nations would help to keep prices down. Drugs in countries like Canada are significantly cheaper than they are in the United States. For example, Gleevec, a cancer treatment drug, costs $6,214 per month for customer in the United States, compared to $1,141 in Canada. One of the major reasons why nations like Canada have such low drug prices is their centralized healthcare system–only one agency in the nation buys drugs, giving it a massive amount of purchasing power. In the United States, individual insurance companies all have to negotiate their own prices, resulting in a significantly higher prices. As previously mentioned, this type of government price control is an option to get these prices. These price reductions can be achieved by allowing consumers in the US to buy drugs for cheaper prices from nations like Canada, giving US consumers the benefits of price control without needing to create a more centralized mechanism to implement it.

In January, Sanders proposed legislation that would allow the United States to import drugs from Canada so that consumers could receive the drugs at a lower cost. Much like Prop 61, this measure failed. The story of its failure, however, cannot be traced to traditional party voting lines in the Senate. Ten Republican Senators, including Ted Cruz of Texas and John McCain of Arizona, voted for the measure. This is likely because both Republicans and Democrats support measures to keep drug prices low. In fact, in 2012 Senator McCain proposed a very similar measure that also failed to pass. Partisan politics did not kill this amendment –thirteen Democrats did. The most notable Democrat to vote against the measure was New Jersey Senator Cory Booker. Booker claims that he voted against the bill because it did not “include consumer protections that ensure foreign drugs meet American safety standards,” making it possible for dangerous medicine to enter the country. However, this measure would have paved the way for future legislation to create these regulations, causing many who support this reform to be weary of this excuse.

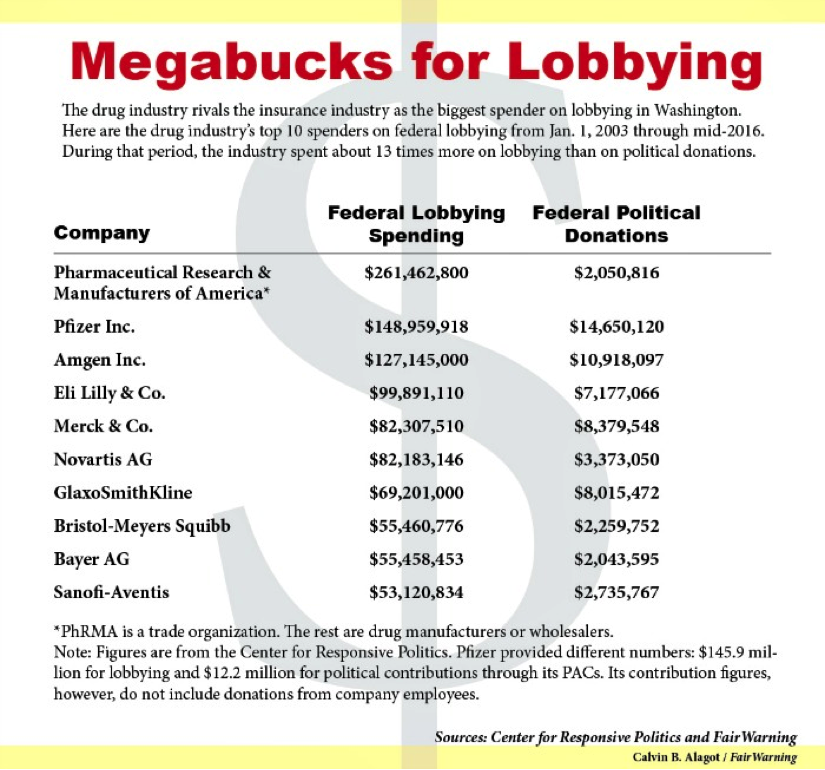

Some believe that Booker voted against the measure because Big Pharmaceutical companies donated $389,678 to his campaign, making them his eighth largest corporate donor. Booker is not the only government official that Big Pharma is donating to –in the last decade, the pharmaceutical industry has spent about $2.3 billion lobbying Congress. This lobbying has a real, verifiable impact. It may have caused Booker and other Democrats to kill the drug bill despite the interests of their constituencies. It also may have influenced the vote on Prop 61 in California. The top ten donors behind the opposition campaign donated $69.8 million to kill the bill. In comparison top donors only gave about $19 million to the “yes” campaign –about three times less.

Studies have shown that economic elites, who have enough money to donate to political campaigns, are more influential than the preferences of an average constituent. This means that the interests of affluent people and companies with the capital to lobby mean more to politicians than popular opinion. According to a 2015 Kaiser Health Tracking poll, about 83 percent of Americans favor the idea of the government negotiating with companies to lower drug prices and 72 percent favor the idea of the US buying drugs from countries like Canada. Yet, as we have seen, these measures have not been able to pass. The pharmaceutical industry has been able to keep these reforms from occurring by lobbying Congress.

The current political landscape in this country and the lobbying power of the industry has made this issue nuanced and difficult to address. But at the end of the day, the focus has to be on people like Jacqueline Racener. They need this reform. The 30 million people who avoid filling prescriptions because of high costs need this reform. Champions of the issue, like Senator Sanders, need to continue bipartisan efforts to break the death-grip of Big Pharma and institute the legislation that ten percent of this country desperately needs.

Featured Image Source: Health Economic Times

Be First to Comment