As a mother of two children and wife to a steadily employed husband, Brianne Reynolds considered herself to be a typical, hard-working American. In addition to taking care of her kids during the day, she worked the night shifts at a local grocery store as a custodian in order to pay the bills. In what has become an increasingly commonplace story for Californians, her family was forced out of her home, as the rent for her small, one-bedroom apartment in the Sacramento area increased 47%, from $610 to $895. Reynolds spoke out: “I have a good job, but all the rents are getting pushed up, even in neighborhoods where you can usually find affordable housing.”

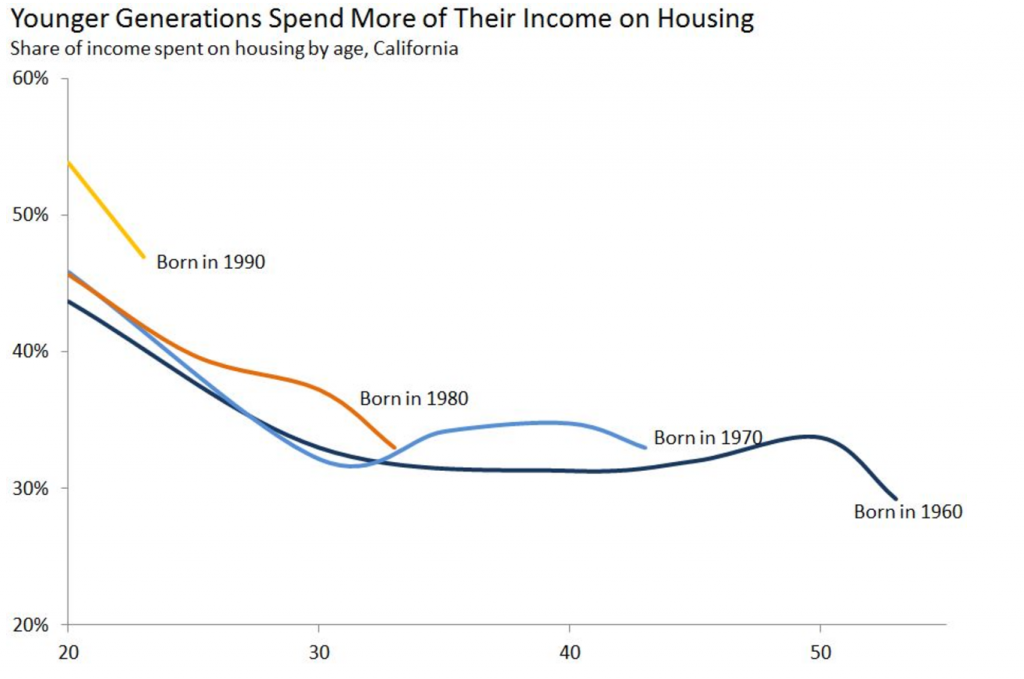

Reynolds is far from alone in her struggles to find a reasonable place to live. California homeownership rates have always been already around 10% lower than the national rate, and they have further plummeted since the housing bubble collapsed in 2008. Younger generations are being hit hard; not only are they spending a larger percentage of their incomes on rent than older people when they were the same age, but they also have lower homeownership rates, both now and as they age. Homeless people are perhaps bearing the worst brunt of this crisis, as California has the largest homeless population of any state—nearly 100,000 people. Even worse, the state has some of the worst conditions for the homeless to live in—75.7% of California’s homeless do not live in sheltered communities, the highest rate of any state. Even relatively wealthy residents can struggle to pay the rent: one Twitter employee who makes $160,000/year can barely afford to live with his family in an “ultra cheap” home in the Bay Area. In a nutshell, virtually everyone is suffering due to California’s lack of affordable housing.

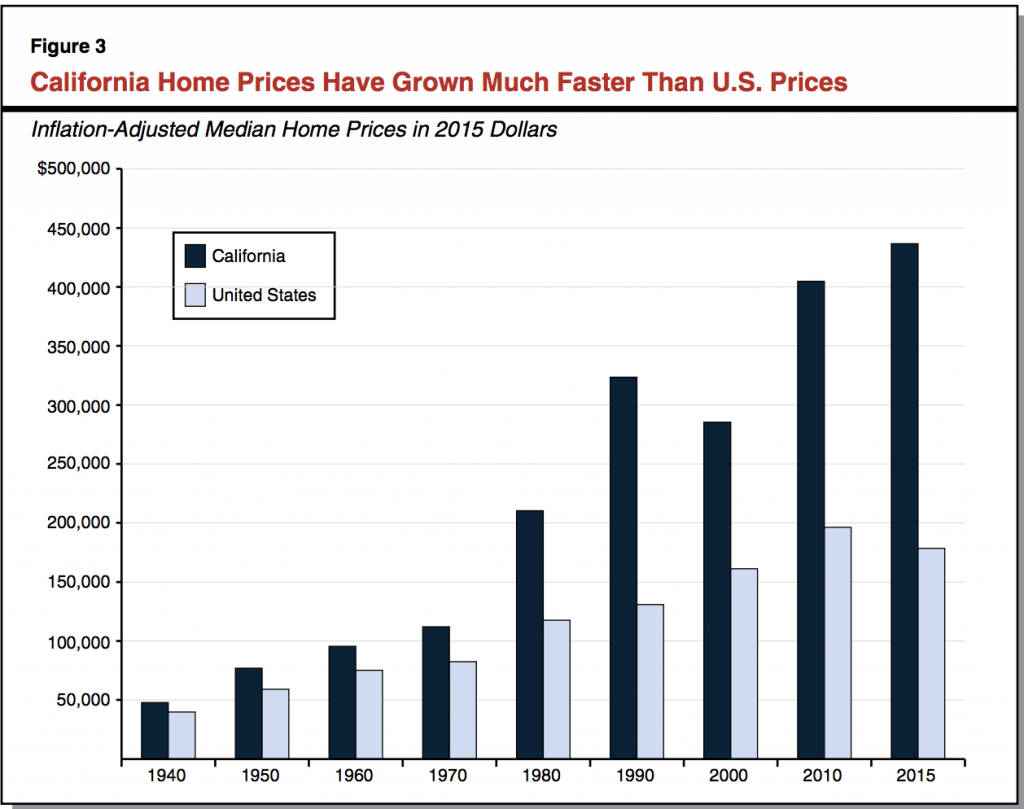

What caused these problems? Typically, as the demand for housing rises, so does the number of houses built. However, this hasn’t been the case for coastal areas. One major cause of this is the slew of anti-growth laws that a majority of large, coastal cities have in place. Residents often fear that new housing could devalue their own existing homes or could drastically change the current neighborhood culture. As a result, over two-thirds of coastal cities have enacted growth control policies that aim to limit housing growth, according to a report done by the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO). This is done by direct measures, like limiting the number of houses that can be built in a given year, as well as indirect measures, such as requiring a supermajority of the local board to approve development projects. California cities also have a deeply entrenched bureaucratic process, with projects taking up to a year to be approved in locations like San Francisco, and even longer if districts have to be rezoned. California’s complicated topography also limits the locations for feasible housing. Living next to a beach is a luxury that many do not have, and most urban centers in California are located near the coast. However, building housing around these cities is not always possible. About two-thirds of all land surrounding California’s most dense urban coastal cities are uninhabitable ocean, mountains, etc. Moreover, coastal areas are already heavily developed, with only 1% of land both vacant and undeveloped. Redevelopment of land is possible but much more expensive.

While it is often for a good cause, environmental legislation such as the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) also exacerbate the housing crisis. Specifically, CEQA has been used by opponents of development to delay and even obstruct housing. Although it has provided important environmental benefits for the state, some anti-growth supporters have used the statute in order to challenge environmental impact reports, which can slow down the process of issuing a permit until all concerns are met. Some have even used CEQA as a political tool: an anti-abortion group utilized CEQA as a means to block the construction of a Planned Parenthood clinic, delaying the construction by over 18 months.

Furthermore, local fiscal decisions play a huge role when municipalities decide what to build. In general, commercial development, such as shops, restaurants, and hotels, produce the highest revenue for an area due to taxes. Contrarily, housing development often leads to increased costs for the city because local costs (public services, infrastructure expansion) outweigh the fiscal benefit. Consequently, cities tend to disproportionately develop commercial areas rather than dense housing units.

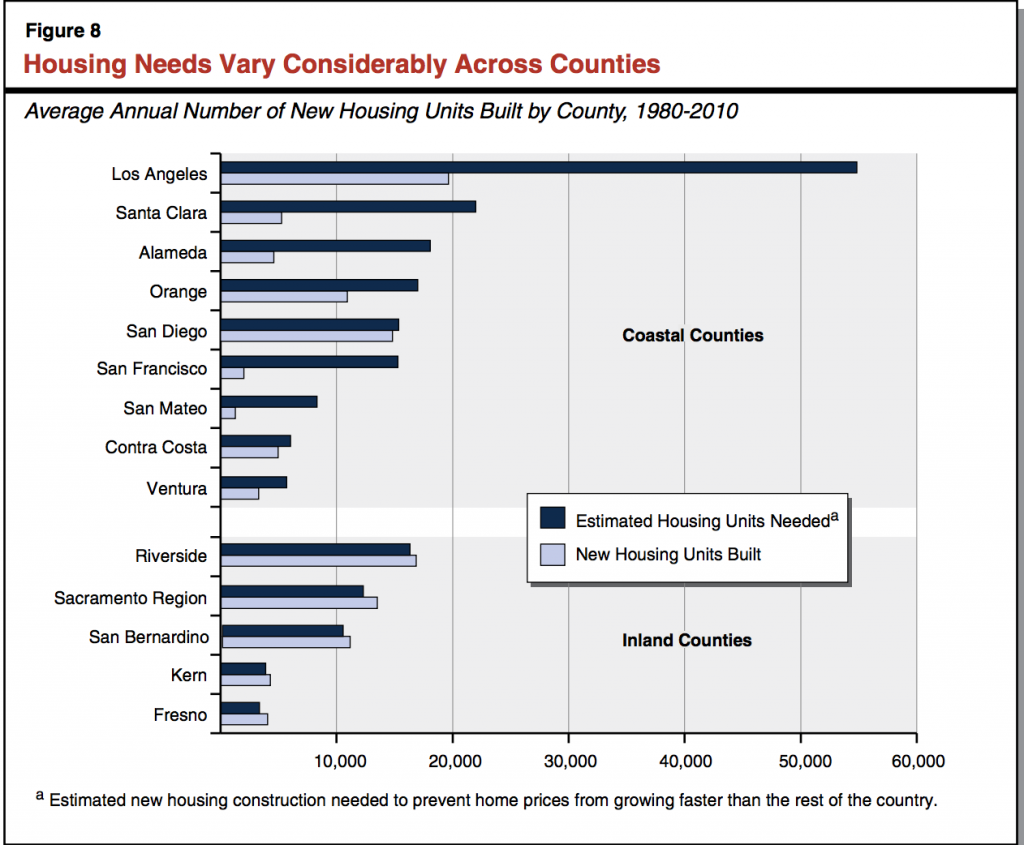

The solutions laid out by the LAO report sound simple in theory, but there is quite a disparity between the answers and the current progress that is being made. California must build around 210,000 new housing units per year; on average between 1980–2010, California built only 120,000 new units. Additionally, more units must be built in both coastal cities and adjacent areas that border coastal cities, as the demand to live in coastal cities is now spilling over into nearby places. As shown below, cities like Los Angeles must build nearly three times as many units than is currently being built. Lastly, housing must be built much more densely than it currently is; new housing must be up to two-thirds denser (population per square feet) than it is right now.

Implementation of policy that would alleviate the housing crisis has stumped lawmakers thus far. In fact, some communities are still fighting challenges that would worsen housing shortages. Recent proposals like Measure S in Los Angeles were disguised as housing reforms that would have benefited the community but, in reality, would have further exacerbated the housing shortage. If passed, zoning changes would have been more difficult and funding would have been blocked for low-income housing and supportive units for the homeless. Fortunately, Los Angeles rejected Measure S, but the mere legitimacy of the proposal shows the uphill battle affordable housing advocates face.

One possible solution that has been brought up is to restrict CEQA. As previously mentioned, CEQA can be used to heavily delay and even halt development projects through its rigorous and time-consuming reviews. However, any attempt to weaken CEQA has met intense opposition from environmental groups and labor groups. Part of the reason why Gov. Jerry Brown’s proposal last May to solve the housing crisis was rejected was because it would have allowed certain projects to skip additional reviews under CEQA. Environmental groups contended that there could be serious damage to the environment if CEQA was reduced, and labor unions opposed the proposal because CEQA protected workers’ health and the proposal could have lowered wages for union workers. There are many other possible reforms, from reducing the ability to sue using CEQA, to prohibiting anonymous lawsuits, to requiring proof of environmental harm before stopping a project. However, none of these solutions are widely agreed upon, so gutting CEQA does not seem to be a likely perspective at this point.

Another solution that has been in works are small lots: densely packed townhomes built in “infill” development, or repurposed vacant land. Small lots are starting to pop up around the state. Although some are sold for astronomical prices in high-end neighborhoods like Venice, many of them are sold at reasonable prices for families in communities like Anaheim and Gardena. This concept has also helped stimulate ideas for housing the homeless. Micropads are a derivation of small lots, but are smaller and a better use of space. These units come pre-built, reducing construction costs, and can be stacked on top of each other, making the most out of the little space available. While the idea is still novel, it is gaining traction, with Sacramento recently starting to debate the use of micropads.

However, in order to truly solve California’s housing crisis, a swift and decisive culture change is needed. Local zoning laws have made rapid development nearly impossible. By limiting the height, size, and number of units allowed, local ordinances that limit growth only exacerbate the problem. Even small lots are now being targeted by zoning laws, which could hamper a potential solution to the housing epidemic. Another source of contention is the fact that many residents support restrictive zoning laws, as they hold a “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) attitude towards additional housing. Part of this is a valid concern. Why allow the possibility of change in your community when there are already no problems? This thought process is dangerous, however, and will only intensify problems for everyone: the homeless, the young, and even the rich (a recent analysis by Radpad showed that engineers at tech companies can expect to spend between 42–54% of their income just to live near their work). A low supply of housing coupled with high demand will continue to drive prices to extraordinary levels. Communities must come together to tear down these anti-growth measures before they start to tear down the communities.

Featured Image Source: Shutterstock

One Comment