For the future of Myanmar’s democracy, the military should be separated from politics in the interest of human rights and stability. Moreover, the United States, a self-styled guardian of democratic sentiments, must not be a bystander while a domestic crisis bordering on genocide unfolds in Myanmar.

Since 2011, Myanmar has been in the throes of a democratic transition from a military junta rule to a military backed civilian government state apparatus. Significant political and economic reforms have been introduced in order to re-integrate Myanmar into the international order and to end nearly half a century of isolation.

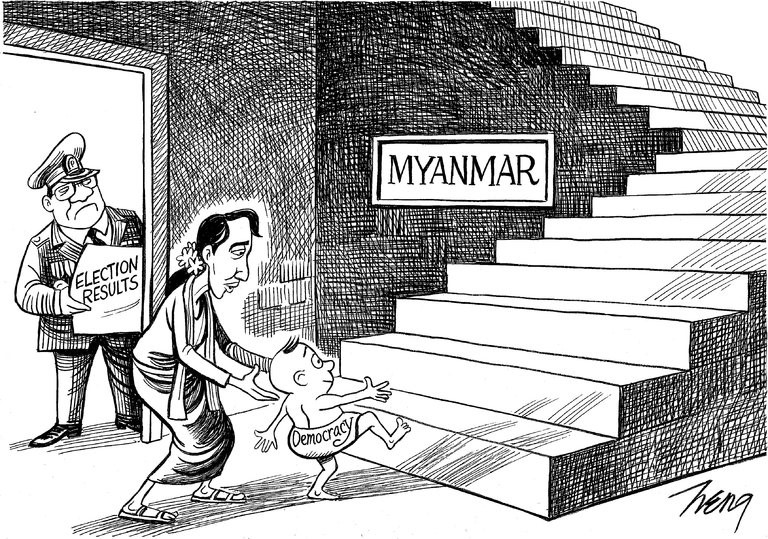

In the historic 2015 parliamentary elections, Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), won a landslide electoral victory that gave it the majority in both chambers of parliament. In response to the changes, world powers have lifted international sanctions, and the United States has resumed diplomatic relations with the country. However, concerns about the role of the military in domestic affairs (the military retained control over important ministerial positions post-2015), the government’s treatment of ethnic minorities, and the recent stagnation in the pace of constitutional reform continue to persist.

With respect to the future of democracy in Myanmar, the United States’ actions will have a powerful effect: the US must decide if concerns over the human rights violations on the part of the military will take precedence over the economic benefits of an alliance with the resource-rich country. The United States must present a tougher human-rights inclined stance towards the military and their emerging human rights violations in order to stem another global humanitarian crisis or genocide in Myanmar. A tough stance towards Myanmar will aid in restricting the influence of the military and in reviving democratic practices in the state. After giving you some essential background on the issue, I outline the necessary steps required to curtail military influence.

Stagnation in Constitutional Reforms

The period of the Thein Sein administration, which governed from 2011-2015, marked a time of fast-paced reform and saw the return of international engagement. His government spearheaded a series of reforms, including the amnesty for most political prisoners, relaxation of censorship, establishment of the National Human Rights Commission and efforts toward peace with ethnic rebel groups. President Thein Sein announced a second wave of economic reforms in mid-2012, vowing to reduce the government’s role in the economy in order to allow for resurgence of entrepreneurship and private initiative. A few months later, parliament passed a new foreign investment law that opened up overseas ownership of business ventures and offered tax breaks in a bid to improve economic conditions. As a result of the democratic transition, Myanmar’s net inflow of foreign direct investment (FDI) increased from $900 million in 2010 to $2.3 billion in 2013, according to the World Bank. Moreover, global powers began reestablishing ties with Myanmar. The United States, European Union, Australia, and Japan dropped some economic sanctions and multinational companies began showing interest in investment in the country.

However, with Suu Kyi’s government, reforms have experienced a drastic slowdown. The military has begun to assume dictatorial powers again in order to control student protests and ethnic-minority rebellions that are threatening to unravel the country. Suu Kyi must make fundamental changes during her time in office if she is to lay the groundwork for economic prosperity and re-integration into the global economy: the military needs be removed from central ministerial positions, the military’s veto over constitutional change must be limited and its autonomy over its own affairs must be replaced with a system of civilian oversight.[5]

The Rohingya Controversy

According to a United Nations report released in February 2017, members of Myanmar’s Army and the police have slaughtered hundreds of men, women and children, gang-raped women and girls, and forced as many as 90,000 Rohingya Muslims from their homes. The military has been engaged in a long-standing campaign to drive out the Rohingya, an ethnic Muslim minority, from the state. The report said the actions of members of the army and the police “very likely” were crimes against humanity. “The gravity and scale of these allegations begs the robust reaction of the international community,” said Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights, whose office released the 50-page report.

The violence serves as a reminder that democratic elections have not significantly changed the traditional power constellation within the state. The close intertwining of the military agenda and national politics will continue to haunt Myanmar, at least in the near future, as the military does not look eager to extract itself from the political arena. Moreover, this controversy has been largely ignored by the international community and emboldened the military in its campaign against the Rohingya in the absence of international scrutiny and pressure. This is because the resettlement of refugees from Middle Eastern countries, particularly Syria, has been the center of heated political debate. The critical take away here is that refugees from Myanmar have quietly outpaced Syrian arrivals in recent years in the United States, despite the intensification of the Syrian civil war, with an increasing number coming from the Rohingya community, according to State Department figures. With the international community turning a blind eye to the situation in Myanmar, the plight of the Rohingya has only been exacerbated.

Aung San Suu Kyi has remained largely silent on the Rohingya issue, sullying her image as an exemplar of democratic values and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. In her few comments about the attacks, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi has largely defended them. “Show me a country without human rights issues,” she said at a news conference. Therefore, the Rohingya seem cornered by inaction on both the domestic and international front.

US Policy towards Myanmar

The United States initially imposed sanctions on Myanmar due to the brutal military crackdown that began in 1988. Successive administrations intensified sanctions, including bans on investment and imports that deeply impacted deteriorating economic conditions. In 2009, President Obama ushered in a new approach to U.S. relations with the country: Washington maintained sanctions, but indicated a willingness to open a dialogue with the ruling State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).[10] This strategy was furthered by Sein’s reforms and led to a thaw in the relations of Myanmar and the United States.

Viewed from the United States’ perspective, the US interest in Myanmar’s affairs span three fronts: democratization, human rights and drugs. Human rights issues, more than strategic or economic concerns, dominated US thinking in dealing with Myanmar initially and led to the imposition of sanctions. But the change in the political dynamics can be viewed as a result of a combination of the following factors: Obama’s pivot to Asia and the need to deal with the rise of China, a desire to tap into Myanmar’s rich natural resources and to enhance defense ties with the country. Myanmar is rich in natural resources such as industrial minerals, oil, and offshore natural gas reserves estimated at 10 trillion cubic feet— commodities that could widely benefit the United States economic future if bilateral trade ties were strengthened.[12] Although China remains Myanmar’s largest investor, there is growing resistance within Myanmar to Chinese infrastructure investment which indiscriminately exploits the country’s natural resources and often interferes with the political process of the country. In light of this, America’s foreign policy changes towards Myanmar could not have found a better opportunity. Harnessing growing anti-Chinese sentiment can help the United States fortify its budding relationship with Myanmar.

During President Obama’s last month in office sanctions against Myanmar were lifted further. The former President declared that this was a goodwill gesture in light of the “substantial progress” that had been made in improving human rights even though the country’s army is in the midst of a brutal campaign to drive out the Rohingya. The human rights community rightfully responded with outrage and protest. It seems that human rights concerns are being relegated to second position and economic agendas are being prioritized.

America’s influence in the international system and its hegemonic role in global politics puts it in a unique position to shed light on the ongoing situation in Myanmar and to aid democratization. However, the current President, Donald J. Trump, has remained largely silent on his foreign policy stance towards this nascent democracy. Trump’s dismissal of human rights as a priority (as witnessed by his desire to cooperate with Russia and Philippines) and his desire to present a stronger stance toward China imply that he would be best served by continuing America’s budding relations with Myanmar. Unfortunately, this stance would require a non-confrontational approach towards the military affairs of the state. This does not bode well for constitutional reforms in Myanmar, the plight of the marginalized Rohingya community and the future of human rights practices.

Featured Image Source: The New York Times

Be First to Comment