“The only way to solve the problem is to admit we have a problem,” said Montgomery County Executive, Ike Leggett, at the town hall. So what is the problem?

On July 19, 2016, Montgomery County organized a town-hall discussion at the Silver Spring Civic Center to allow residents to express their concerns about local police, The event was a response to the increase in incidents of police brutality against the Black community in recent years. Fatal shooting of Gregory Gunn, a 58-year-old African American grocer, in West Montgomery on February 25, by a white cop was the nail in the coffin for relationships between the police and community. Gunn’s case illustrates how the criminal justice system carries on a legacy of racism that has resulted in the latest string of tragic shootings. Institutional racism can be understood by analyzing different factors inside a community. Race issues in Montgomery can be divided into four parts: poverty, crime, policing, and the community. My goal is to address each of these parts as the root causes of all tensions within Montgomery’s criminal justice system, and beyond.

Incidents of police brutality are not one-off events where ‘bad’ cops abuse their power against black people. Instead, these instances should be understood as a manifestion of systemic racism in places like Montgomery which requires us to take a historical perspective to understand why incidents like the fatal shooting of Gregory Gunn are so commonplace in modern America. Montgomery’s history goes a long way in explaining why black people there live under a police state.

Residential segregation in one of the root causes of poverty among African Americans in Montgomery. “White flight” is a term used to describe the movement of white people to new suburban areas. Federal policies enacted during the 1930s ensured that African-American neighborhoods in Montgomery suffered rapid economic decline after whites fled the region. The Federal Housing Administration was created in 1937 with the purpose of giving low-interest loans to families. Discriminatory practices within the FHA favored white applicants and ensured loans went to borrowers in white communities. In addition, restricted covenants prevented white homeowners from selling their homes to black families. According to some theories, race was considered a factor in neighborhood decline, which can be avoided through segregation.

Furthermore, access to Montgomery was severely restricted when President Eisenhower started the Interstate Highways Project in 1956. Coupled with the aforementioned housing discrimination, African Americans faced a dire situation which displaced more than a thousand families. Routes I-65 and I-85, spearheaded by a highway director who was also a high level member of the Ku Klux Klan, divided affluent African American neighborhoods and bisected neighborhoods housing black activists. An alternate route through vacant land was rejected. This created an increase in demand for housing which gave developers another chance at marginalizing blacks in certain neighborhoods.

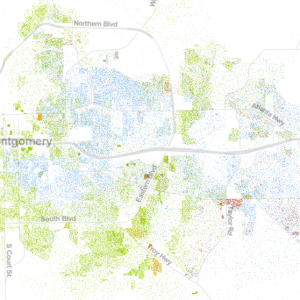

As the map shows, Montgomery is still severely segregated despite increasing awareness and reforms. Green areas are black neighborhoods and blue areas are white neighborhoods. Red areas are Asian neighborhoods.

White flight was on display again when a district judge in Alabama approved what was then called the “nearest school plan,” which segregated black and white school districts. White homeowners sold their houses in a state of panic, often underselling and incurring large losses. Steering people towards particular neighborhoods based on race was also one of the root causes of economic decline. In U.S. v. Pelzer Realty Company, Inc, Pelzer Realty refused to sell houses to two black employees in an all-white neighborhood, instead offering to build them houses in one of the other black neighborhoods in Montgomery. These policies were responsible for concentrating poverty in minority neighborhoods while white neighborhoods flourished. As the map shows, Montgomery is still severely segregated despite increasing awareness and reforms. Green areas are black neighborhoods and blue areas are white neighborhoods. Red areas are Asian neighborhoods.

“Poverty,” wrote Aristotle, “is the parent of crime.”

Research done in Sweden revealed that teenagers who grew up in households whose earnings were among the bottom fifth were seven times more likely to be convicted of violent crimes and twice as likely to be convicted of drug offences. Perhaps this research does not surprise anyone, but it provides a framework from which to look at Montgomery. According to the FBI’s uniform crime report for the year 2015, total crime rate in Montgomery is 65% higher than the national average, Montgomery is safer than only 16% of the cities in the United States and murder rate is almost 3.5 times the national average.

Median household income for the entire city is $42,927 compared to $53,889, which is the national average. At the same time, African Americans are the most common race living below the poverty line. About four times more blacks as whites are poor in Montgomery. These figures not only show a direct correlation between crime and poverty, but also show that African Americans still live considerably poorer lives than other residents.

With a high crime rate, Montgomery can be expected to have a higher number of police force to implement law enforcement throughout the city. But what happens when the police commissioned to a certain area is not acclimatized to the culture of a community? The answer to that question is greater resentment and fear. Police members who cannot reflect the community they serve cannot be expected to handle cases in an unbiased way.

Earnest Blackshear, a professor at Alabama State University and a clinical psychologist thinks “poverty leads to a lack of education and lack of access to mental health care.” Kids growing up on the streets of Montgomery live by a street code, which is a kind of value system learned in prison. Some of them even own guns. They learn to “retaliate immediately” and live in constant fear. According to Blackshear, 10 per cent of the black community communicates through “gangster rap” that preaches violence. Whether all or part of this is true, a person unfamiliar with Montgomery’s culture cannot possibly be expected to handle situations in the most appropriate manner. He or she will probably perceive a greater risk than actually exists and react more violently to relatively mild affairs. The right solution does not necessarily involve black cops in black neighborhoods. However, cops educated about the place they are being commissioned to can go a long way into making lives more peaceful for black communities in Montgomery.

I have addressed the first three parts to my argument: poverty, crime and policing. To address the last part, community, I would like to present a very glaring statistic.

The 3 year recidivism rate in Montgomery is 37.7%. Which means that for every 100 people released from prison, roughly 38 of them commit another crime. Also, 31.7% of ex-offenders are involved in a new crime which takes them back to prison. African Americans lead the 3-year recidivism rate for rearrests, reincarnations, and overall recidivism. A higher recidivism rates means higher crime rates and lesser public safety. The statistic highlights the lack of employment, educational, emotional and substance abuse support once an offender is released from prison. Mass incarceration disintegrates the community structure and pushes families and neighborhoods further into poverty when breadwinners are regularly locked up. Furthermore, the lack of services provided during prison time because of overcrowding affects an offender’s ability to integrate back into the community after release. It also shows unfair follow-ups with the police who exercise great authority by stretching the legal basis for stop and search and holding themselves accountable after a complaint. Parents live in fear as they teach their children proper engagement.

There a number of ways these issues in Montgomery can be addressed. Hiring more representative juries, considering drug abuse as a health issue instead of criminalizing addiction, listening to the needs of the community, and removing the stigma associated with convicted criminals, are other examples. While some might consider these changes progressive, lack of action in these areas will simply continue the downward spiral of crime and poverty prevalent in places like Montgomery.

With reforms in these areas, it is possible that Gregory Gunn would not have died for simply carrying a ‘retractable painter’s stick,’ and he would be amongst us, alive and well. His story shows that widespread reforms in Montgomery, and other black cities facing similar troubles, are needed to allow everyone to pursue liberty and prosperity, two values that are at the heart of the American dream.

There was a moment during the town hall that highlighted the magnitude of change needed to improve black lives.

A teenage girl attending the attending the town hall said, “I used to want to be a police officer… then my dreams were crushed in several different ways.”

Featured Image Source: BBC News

Be First to Comment