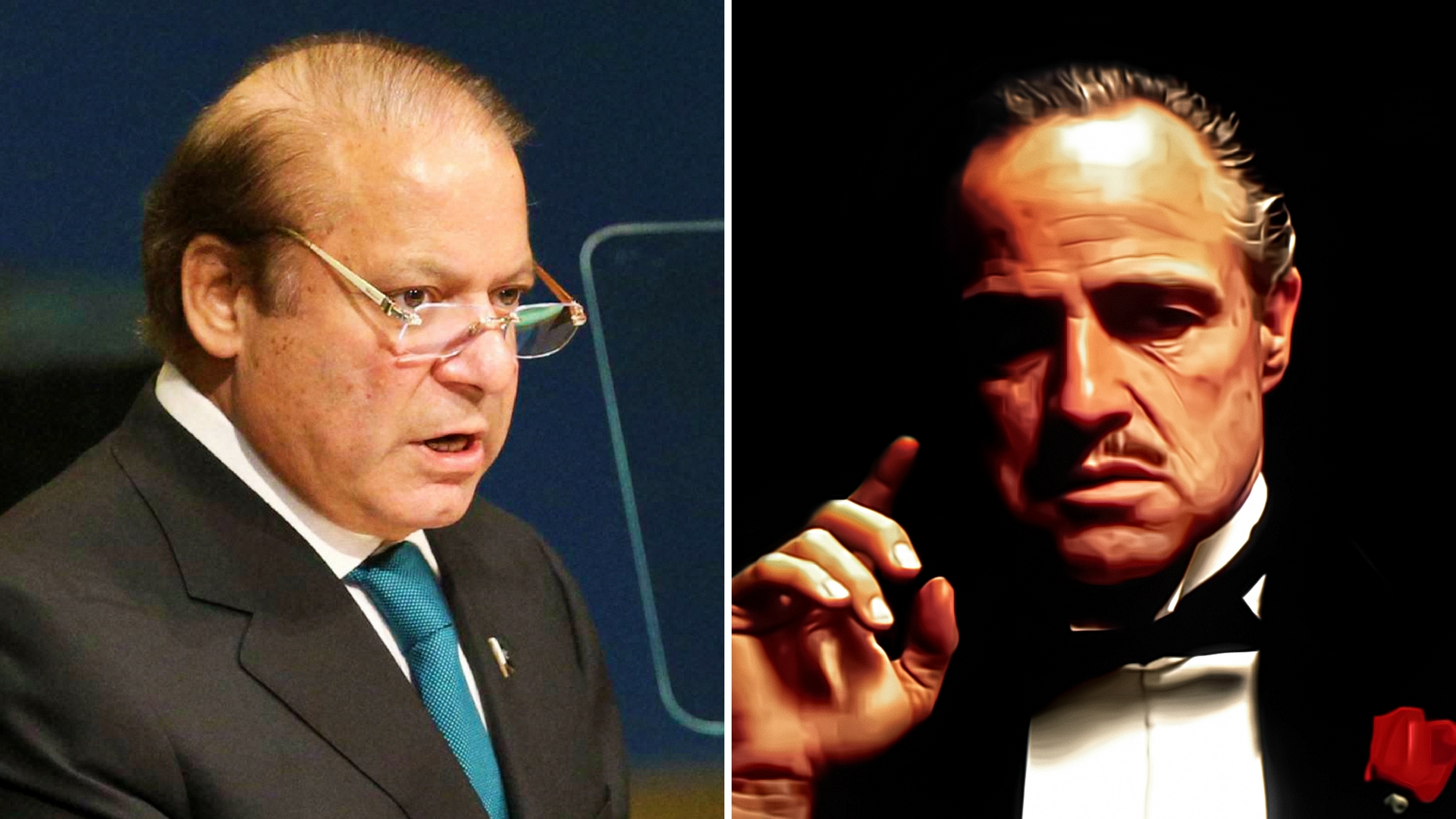

Pakistan’s former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted in July this year on allegations of corruption and money laundering. The Panama Papers leak linking Sharif and his family to several offshore companies sparked a Supreme Court inquiry into their financial dealings over the years. The case, however, quickly started to resemble a reality tv show more than an independent investigation.

In the very first sentence of the verdict, Supreme Court used the word “godfather” to reference Sharif family’s wealth and power amassed through allegedly illegal means.

This is how the infamous verdict started: “The popular 1969 novel ‘The Godfather’ by Mario Puzo recounted the violent tale of a Mafia family and the epigraph selected by the author was fascinating:

Behind every great fortune there is a crime – Balza,”

Referencing the best-selling crime novel is certainly a very interesting way to start a historic verdict, to say the least. The Godfather tells the story of a fictional mafia living in New York headed by a guy named Vito Corleone. Whether or not the Supreme Court meant to overlap the identities of Corleone and Sharif is a separate discussion, but news media and the public alike were struck by the apex court’s choice of language. By going down that road, the Supreme Court diverted the inquiry away from Sharif’s deeds and actions and into his moral character. Regardless of the strength of the evidence presented against Sharif, using this language was a huge error as it politicized the investigation and portrayed the judges as media savvy. It also sent a negative signal to other countries.

Furthermore, outdated laws, the evidence amassed through alleged extrajudicial means and questionable reasoning devise a final verdict marked with potholes. There are also allegations of military pressure exerted on the apex court to influence its decision, which has put the impartiality of the Supreme Court under the spotlight. So far, there have been more questions than answers; and while the nation is again steered through turbulent waters, people are heading to the deck to find out who commands them. Whether or not there is a silver lining in the midst of all the turmoil will depend on how the country chooses to interpret these facts and act accordingly.

The Supreme Court’s process to disqualify the prime minister was divided into two phases. On April 20, the first phase 3-2 verdict came out came out in favor of Sharif. The two dissenting judges referenced the prime minister’s dishonesty as reason enough to disqualify him. The majority, however, cited insufficient evidence and ordered further investigation with the help of a Joint Investigation Unit (JIT). The unit was authorized to engage relevant local and international authorities to investigate Sharif’s offshore assets.

The controversial language referenced in the first paragraph was part of the first phase. However, those strong remarks were not able to tip the scales in either direction and the case was extended for two more months as a result.

Moving on to the second and final July 28 verdict that led to Sharif’s eventual demise. Supreme Court’s judgment was based on a piece of evidence which elicited an undisclosed, unwithdrawn salary of 10,000 dirhams from Nawaz Sharif’s days as the Chairman of Capital FZE, a Dubai based textile company. Court argued that Sharif ought to have declared the salary in his 2013 election nomination papers because it was a receivable, and hence an asset. While not declaring assets does amount to a crime, it is important to question whether Sharif did actually break a law. Supreme Court invoked Article 62(1)(f) of Pakistan’s constitution on the basis that Sharif was not “honest” and “trustworthy” with the country. The problem with that argument is that for Sharif to be dishonest, he had to have had the intention of lying. For example in a homicide, the prosecution has to prove an intent to kill on part of the suspect for the incident to be considered a murder. Otherwise, it is just an accident of manslaughter which constitutes far lesser punishment. Similarly, in this case, the court had to establish whether the omission of that relevant detail was deliberate or just a mistake on Sharif’s part but, unfortunately, it was not taken into consideration. While no law is too great for an elected leader and no elected leader is too great for punishment, elected leaders still reserve the right to due process and proper interpretation of the law.

With so many unanswered questions and ill-addressed concerns, people of Pakistan are starting to consider whether Nawaz Sharif was punished for crossing the military. It is the same old question which has gripped the country at its roots for seventy years.

Unfortunately, Pakistan’s civil institutions have always remained in the shadow of military influence. Nawaz Sharif himself has been at times the most avid supporter of the military and at others its harshest critic. His approval depended on how the military was willing to support him in his endeavors. During the regime of military dictator Zia-ul-Haq, Nawaz Sharif served as Chief Minister for Punjab and remained loyal to him even after his death in a plane crash incident in 1988. However, when Sharif became prime minister for the first time in 1990, it was pressure from the military that led him to resign three years later. In 1996, Sharif became prime minister for the second time and made an ill-fated decision to promote General Pervez Musharraf to Army Chief, a man who eventually overthrew Sharif to end his second of three unfulfilled terms as prime minister.

From enjoying the most friendly to having the most fraught relations with the military, Nawaz Sharif had already etched himself between two hard places. So when the most recent saga unfolded, it was natural for Pakistanis to raise their eyebrows and speculate about backstage influences on the apex court. After all, the court has not given people enough reason to dispel this particular notion.

Supreme Court of Pakistan has demonstrated malleability in ethical standards when it comes to defending the country against authoritarian leaders while often taking harsher stances against civilian leaders. The court has legitimized all three successful military coups in 1958, 1977 and 1999 under the “doctrine of necessity.” The civil-military nexus is so vast and its arm-twisting so commonplace that people have accepted military intervention in civilian issues as the norm. For example, when Pakistan cricket team won the Champions Trophy beating archrivals India in the finals this year, Army Chief Qamar Javed Bajwa announced pilgrimage tickets for the entire team. Unquestionably, those were times of great jubilance for the country but it is inappropriate for the military to make such gestures, in light of more pressing matters of national defense.

Even though the Supreme Court’s decision was questionable in nature, it does not permit Sharif and his party to ignore years of dubious political and financial practices which are well documented and known to the public. Sharif has to keep in mind that even though the apex court made a mess of the formal indictment process, there are incidents in the past that could have been just as costly towards his political future.

For example, the Mehrangate scandal which unfolded during the 1990 general elections brought to light 400 million rupees ($4,000,000) disbursed to various politicians at the behest of then Army Chief Mirza Aslam Beg with help from the intelligence community. The money was used to rig the elections against the incumbent government of Pakistan People’s Party. Sharif, who won those elections and became prime minister, is alleged to have accepted 3.5 million rupees ($ 35,000) from the sum amount.

Shahzad Chaudhry, a defense analyst based in Pakistan, wrote a 2012 op-ed on the Mehrangate scandal in which he wrote that the “elected and electorate inhabit two different worlds” in Pakistan and that the real constituency of elected leaders is the “mass of people” who put them in a position of power.

“And, then the question why aren’t our politicians respected. Shall we respect thieves and extortionists and looters and plunderers,” Chaudhry wrote further. “That is the question that the people ask of their political masters. In the name of democracy, what more shall this hapless nation be subjected to?”

Despite all that, the former premier is using this opportunity to kick-start his party’s 2018 elections campaign. With a new prime minister in Shahid Khaqan Abbasi and a revamped cabinet to focus on intricate matters of state, Nawaz Sharif finds himself in perfect conditions to play the role of a political martyr. In August, he started a multi-day rally down the infamous Grand Trunk Road stopping at different points along the way to make resounding speeches in an effort to strengthen his base and align the public with his newfound cause of constitutional reform.

It was obvious, however, that while Sharif hopped from city to city berating the Supreme Court’s decision and making insinuations towards the military, he played the oldest trick in the political playbook. Sharif has chosen to play the victim and blaze a path forward, instead of admitting past mistakes. Article 62(1) introduced in the Constitution during the military regime of Zia-ul-Haq is an absurd law. With proper enforcement, this law has the potential to bring an end to the political careers of virtually every single elected leader in this country, as it did for Sharif. Sharif had one four-year term and two three-year terms in office, in addition to all those years as leader of the opposition in the National Assembly, and still he failed to inculcate meaningful change. Sharif should not get to play victim now that the snake has bitten him from the back when he had the option of cutting its head all along.

It is also worth noting that while Sharif condemned opposition leader Imran Khan for leading a rally towards Islamabad and hijacking the capital in 2014, costing large amounts in economic losses, his GT Road march was not much different. This attitude elicits the notion that the values of our leaders are present as long as they have skin in the game, and the principles they champion vanish as soon as political stakes are lessened. While the country has weathered duplicitous behavior from its leaders in the past, Sharif’s self-obsessed campaign could have potentially devastating effects for the country’s future.

Pakistan’s leaders must come to terms with the fact that reform is a gradual process which requires grit and persistence. Reform comes from a desire to change, not a desire to hold public office. While Sharif’s promises sound revolutionary; Pakistani citizens must realize that similar promises have been made in the past by vulnerable leaders desperate for support. Now more than ever, it is crucial to take what these leaders promise with a grain of salt.

As Abraham Lincoln said: “Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.” And Nawaz Sharif has seen a lot of power over the years.

There was no better opportunity for him to become a model leader and bring young and talented local politicians to the main scene. Instead, he decided to adopt the strategically safer route of nepotism to announce his wife, Kulsoom Nawaz, as his successor. While no one is questioning the ability of Kulsoom to make a good prime minister, people are, however, blaming the former prime minister of consolidating power within his family. It is widely known that if Sharif’s daughter Maryam Nawaz had not been referenced along with her father in the Supreme Court’s decision, she would be the natural successor.

Partly because of the interference of outside groups and partly because of the inactivity of its elected leaders, Pakistan is still a fragment of the country it set out to be. In order to ensure the country embodies the vision of its founding fathers, Pakistan ought to strive for institutions shielded from the forces of power groups, a proactive and functioning legislature that acts on the mandate that gets them elected, true oversight including equal checks and balances on leaders and the public, and a prioritization of public demands over lobbying groups, both local and international. This is a lot to ask from a country that has yet to see the light of true democracy but one can only hope.

Millions see the Panamagate decision as the beginning of a new era for accountability and various factions have taken it as fuel to propel them forward in this final stretch before the 2018 general elections. There is no doubt that such open-ended accountability of some of the most powerful people in the country is unprecedented in the nation’s history and commendable in its own right. But before the complacency sets back in, it is important to ask ourselves whether democracy in Pakistan will actually take a step forward or a step back. Only time will tell.

Featured Image Source: The Quint

3 Comments