Crossroads Blues

In 1965, the city of Singapore was kicked out of Malaysia. It was poor and isolated, with an economy wholly subsidized by Britain’s Royal Navy. To the north, Malay extremists threatened to instigate a coup and regain the island. To the south, the Indonesian military toppled the pro-communist government, killing millions and threatening the entire region’s stability. At the head of this vulnerable city-state, responsible for the futures of almost 2 million Singaporeans was the British-educated Lee Kuan Yew. Lee saw before him a crossroads: poverty or prosperity, democracy or dictatorship.

Lee’s Deal

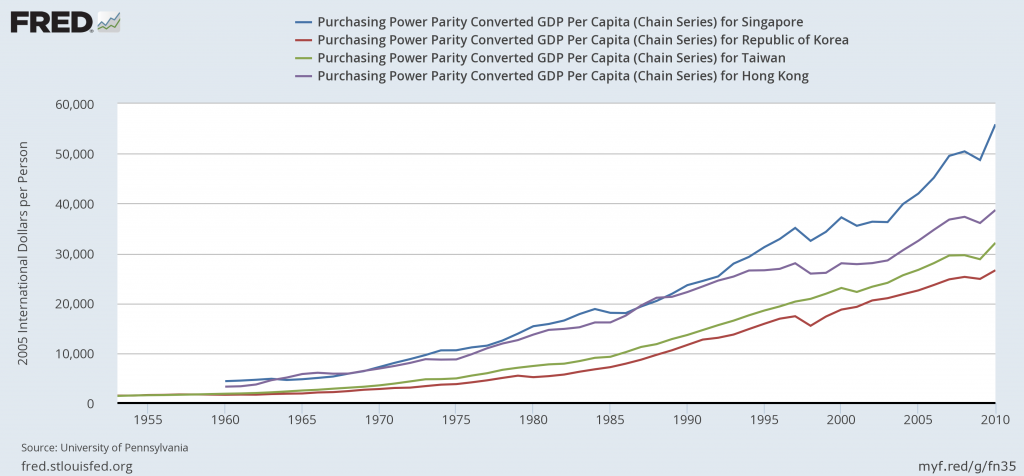

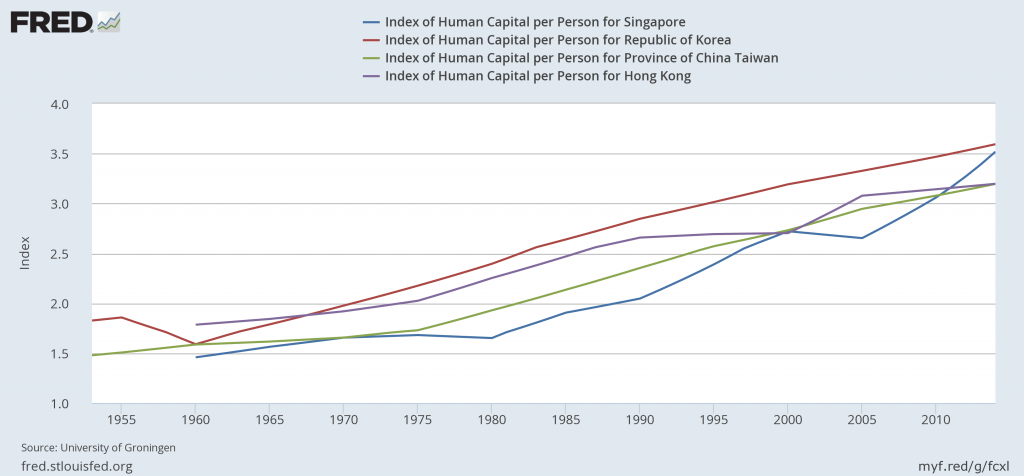

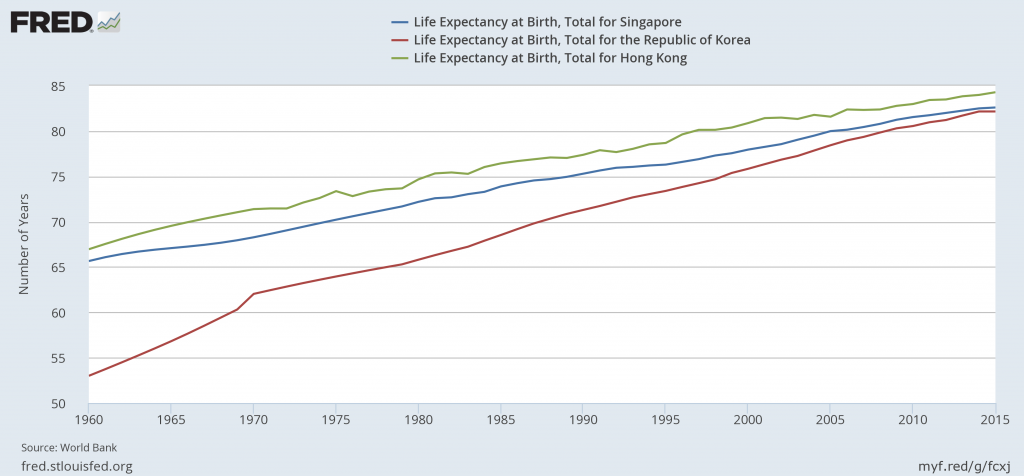

The Singapore of today looks nothing like the Singapore of 1965. Since 1960, GDP per capita rose by thirteen times, life expectancy increased by 17 years, and the human capital index more than doubled. The Port of Singapore, once dependent on Western naval bases, is now one of the busiest in the world, transferring over a billion tons of cargo annually. By any objective measure, Singapore has risen from squalor to splendor, matching and even exceeding developed countries like the United States on any number of metrics. Lee Kuan Yew made the right decisions for the economy. Nevertheless, his choice was very much a deal with the devil.

Coinciding with this rapid growth was a constant, undemocratic domination of Singapore politics and society by Lee and his People’s Action Party (PAP). For the first fifteen years after independence, no other party held a seat in the parliament. The party’s worst showing was in the 2011 general election, winning only 60.1% of the vote and 81 out of 87 seats in the parliament. Every single president has been tied to the party and all but one rose to the position without an election. In the 2017 presidential “election”, only one candidate was deemed eligible to run: Halimah Yacob, who, unsurprisingly, was the candidate backed by the PAP.

To call Singapore authoritarian, however, is difficult because it does not fit traditional notions of what is and is not authoritarian. Singapore does not purge; it does not kill. It is not ideological, genocidal, or warlike. The government is nominally democratic, it functions, and it scores well on indices of corruption. Singapore is a pioneer of what Guriev and Treisman from the London School of Economics call “soft autocracy”: Instead of controlling the people directly, the PAP uses information and manipulation to maintain their rule.

An Abusive Relationship

To see how Singapore’s government treats information in the country, one need not look farther than Reporters Without Borders. For 2017, they ranked Singapore 151 out of 180 countries on their Press Freedom Index, putting it below the oligarchy in Russia and the military regime in Thailand.

Much like their democracy, Singapore’s press is nominally free: Article 14 of the Constitution specifically protects freedom of speech and press. However, all radio and television broadcasting is controlled by the state-owned Mediacorp. All print media goes through Singapore Press Holdings, a private company with a list of former directors that reads like a roll call at the Prime Minister’s cabinet meeting. Finally, films, music, video games, performances, news media, and even the internet are subject to regulation and censorship by the Orwellian Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. The government does not even have to overtly exercise its regulatory power as its sheer influence causes widespread self-censorship among journalists. If critics or dissidents do manage to publish critical or opposing pieces, they are frequently prosecuted under strict defamation laws, sometimes being charged with “sedition” for a maximum of 21 years in prison. The result is a society in which you are free to vote, but not free to know.

The government provides a variety of justifications for this authoritarian hold on politics. In his book, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, Lee Kuan Yew constantly cites Singapore’s unique situation with a heterogeneous population and weak geopolitical position as requiring firm leadership. Prime Minister and son of Lee Kuan Yew, Lee Hsien Loong minimizes the government’s actions by labelling it as simply enforcement of the rule of law, a necessity to maintain Singapore’s economy amid all its challenges. Law Minister K. Shanmugam deflected criticism at the New York Bar Association by claiming Singapore cannot be looked at as a country; instead, Singapore should be seen as a city comparable to New York or Chicago which are also held by single parties.

All of these justifications stem from two key arguments. First, Singapore is different and thus requires different solutions, and second, only the PAP can lead Singapore. Lee’s choice at the crossroads — authoritarianism over democracy, prosperity over poverty — is inextricably linked to these arguments. In the historical canon espoused by the Singaporean government, Singapore’s position in 1965 was so terrible it needed a savior to drag the country from third world to first. This claim can and should be tested.

Comparing Progress

To be clear, Lee Kuan Yew and his party managed the Singaporean economy well; to say otherwise would be a blatant lie. However, when the government draws the conclusion that only Lee Kuan Yew and his party could have managed the economy well, they are also lieing. Refer back to the earlier statistics detailing Singapore’s prosperity: a 13x increase in GDP per capita, a 17-year increase in life expectancy, and a doubling of the human capital index. When compared to most developing countries, this growth seems amazing, but when compared to Singapore’s peers, these numbers are not particularly striking.

Accessed from: Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED)

Source: University of Pennsylvania

Accessed from: Federal Reserve Economic Databe

Source: University of Groningen

Accessed from: Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED)

Source: World Bank

In South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, all of these improvements were attained, and in some cases, beaten. All of this with greater geopolitical threats, greater political instability, and far poorer starting conditions. Most importantly, all three are today democratic. South Korea ditched a US-backed dictatorship in 1987, and now has a democracy hailed by some as the gold standard. Around the same time, Taiwan ended the one-party rule of the Kuomintang that had lasted since their exile from the mainland, and is now using their democracy as a point of judgement against their rivals in Beijing. All the while, Hong Kong has maintained a constant democratic tradition under first the British and now the Chinese. In none of these places did democracy ever serve to slow down the pace of growth and development, in fact, part of Hong Kong’s slowdown in the 1990s can be directly attributed to fears regarding its reintegration with the authoritarian China.

Moving beyond Asia and considering the rest of the world, the unnecessity of authoritarianism becomes increasingly clear. In fact, a 2014 article by academics Acemoglu and Robinson found that democracy itself has “a significant and robust positive effect on GDP.” For Singapore to continue claiming otherwise is to paint a dishonest picture of their history. Yes, Singapore was poor, isolated, and vulnerable; however, authoritarianism never did anything to help.

Once Again, a Crossroads

The justifications provided by Singapore are disrespectful to democratic reformers across the world in general and to those in Singapore in particular. These reformers fight long, hard battles to win people their freedoms and to slander the process as Singapore has is almost as shameful as the acts they wish to defend. For inspiration, Prime Minister Lee should look back to his father, who in 1955 said, “If you believe in democracy, you must believe in it unconditionally. If you believe that men should be free, then, they should have the right of free association, of free speech, of free publication.”

What is more, however, is that Singapore is not alone. Across the world, countries are grappling with the growth of authoritarianism and oppression and many in the third-world, who feel like the West’s prescriptions have failed, are looking to alternative models of development. Even the People’s Republic of China looked to the “Singapore Model” as an example for their own country when they abandoned Maoist economics in the 1980s. Singapore’s economic success is a siren song that continues to luring unwitting countries to dictatorship and, ultimately, despair. In this, Lee Kuan Yew has turned his country into the devil that first tempted him in 1965.

The road ahead of Singapore today is, once again, a crossroads. The leadership of Lee Hsien Loong is no different from that of his father. Presidents are still chosen, rather than elected; journalists are still silenced, instead of heard; and the people are still controlled, instead of freed. Worse, however, is that Singapore does not have to do any of this. Singapore’s prosperity derives entirely from its economic freedom, not its political oppression. To continue on this path of authoritarianism would be a disservice to all in Singapore. The call for democracy will continue to grow until it is answered.

Featured Image Credit: BPR Designer Anna K. Wysen