“Bright” is the word that might best describe the United States’ economic powerhouse: Silicon Valley. Yet while San Jose and Palo Alto sparkle in the political spotlight, Midwestern towns of Detroit and Dayton have been left in the dark.

For the last two decades, while manufacturing towns in the Rust Belt have declined, Silicon Valley has become the American economic darling. Just last month there was the announcement of the iPhone X, which is predicted to propel Apple to a net worth of $1 trillion. Simultaneously, the approval of the Amazon-Whole Foods merger brought major discounts to customers of the major retailer. Yet despite the growth of Silicon Valley, the tech industry has been ineffective at dispersing this wealth equally among the American people. The Big Four (Facebook, Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon) all struggle to help transfer their success to the rest of the American people because of the lack of investment in different regions, lower labour demands, and possibly by unfair competition.

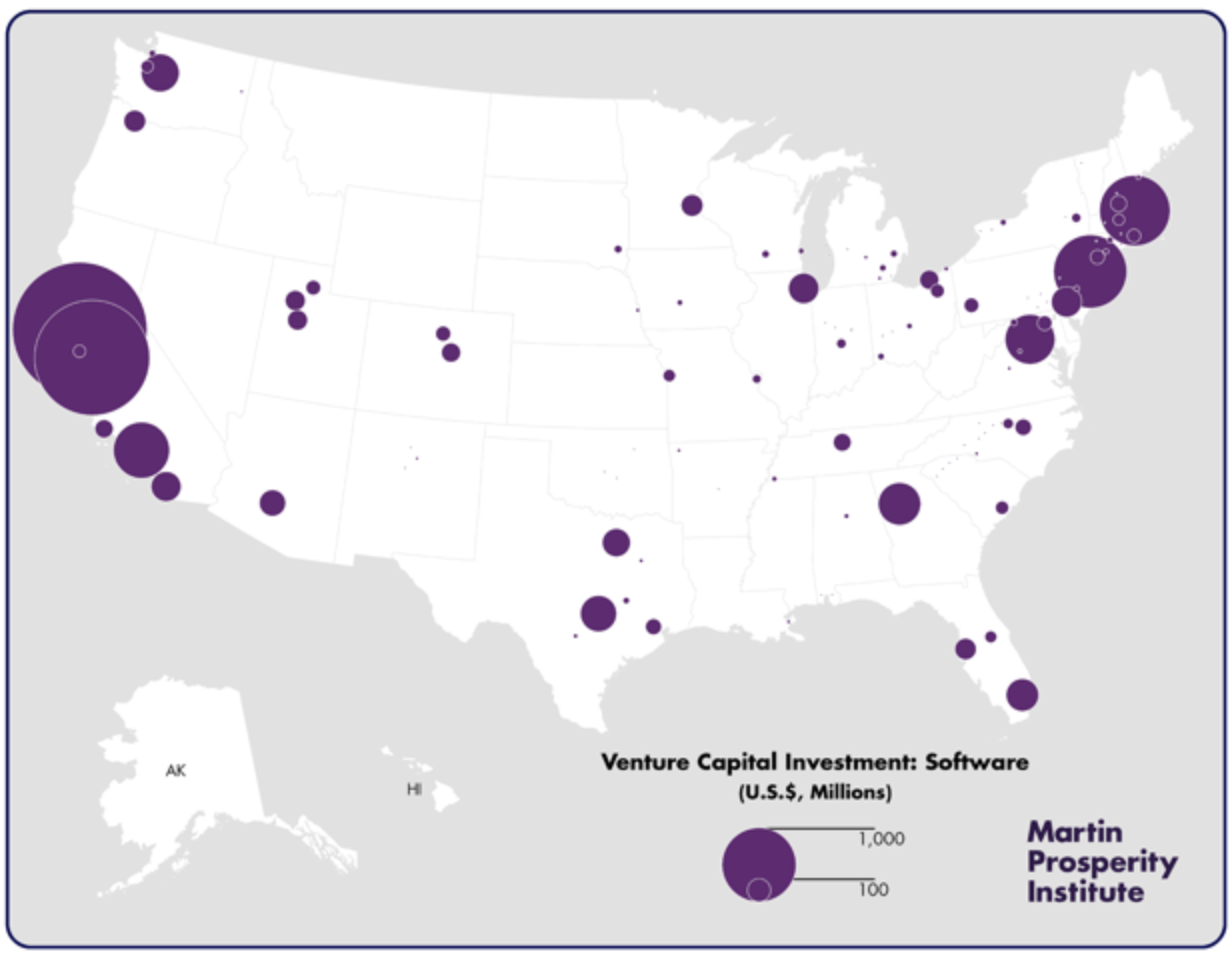

With the rise of automation in the 21st century, a massive hole has been left where manufacturing jobs once were. While California has experienced unprecedented growth, regions like the Rust Belt which have long needed the presence of new industries, are the least likely to attract tech companies. Tech companies are unevenly distributed across the country. For example, the city San Jose has five times the number of software developers than the average American city.

Ultimately, this regional issue is a problem that tech companies can’t manage on their own. Tech companies center around cities with universities that have large supplies of college graduates. For instance, College Station, Texas, is a perfect model of a small college town that has become a center for the telecommunications industry and software development. The Rust Belt on the other hand has historically received less research funding than Silicon Valley. In 2005, the Midwestern U.S. received only 7.3% of the federal government’s R&D spending while having 22% of the U.S. population. Noah Smith, a tech writer for Bloomberg described the issue of Midwest institutions in a simple example, “Massachusetts Institute of Technology-in-Flint already exists — it’s called the University of Michigan-Flint. It’s just not as good of a research institution as MIT.”

To address the geographical issue, the U.S. government has a couple of different options that would attract tech firms to the Rust Belt. First of all, tech companies which mainly have contracts with the US military like Raytheon, Boeing and Lockheed Martin are incentivized to maximize their impact across several states. These companies remain competitive by offering contracts that distribute employees across state lines. When negotiating contracts with Silicon Valley companies, the U.S. government could give priority to firms who are willing to employ people in areas like the Rust Belt. At the same time local governments in “suffering” regions could use tax credits to incentivize the growth of tech in their region, like Georgia incentivized the film industry to establish a presence within its state. The U.S. government could also reverse its history of underfunding research institutions in the Midwest in order to attract larger tech companies.

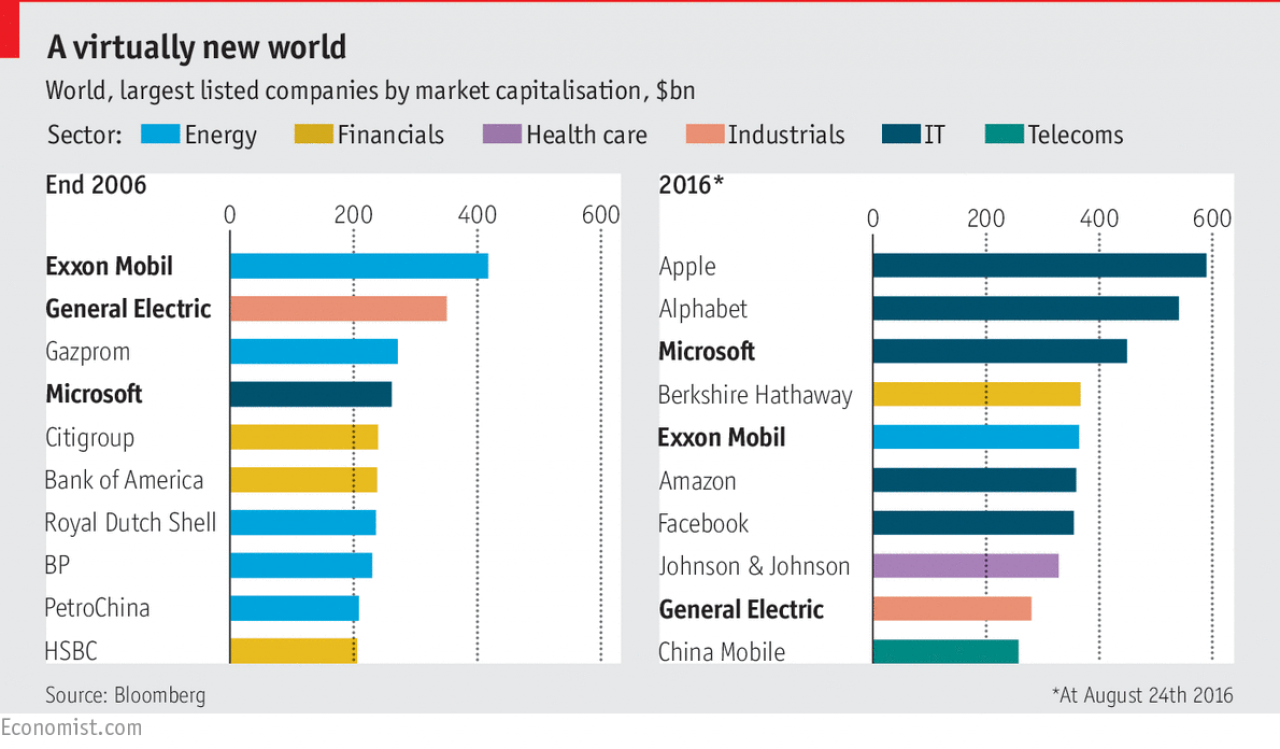

Furthermore, Big Tech also struggles with filling the void of the pre-automation manufacturing boom. For instance, General Electric a titan in US manufacturing, has 333,000 employees, while Apple employs only 116,000. But when it comes to total worth, Apple is valued at $815 billion while GE only has a total worth of $223 billion. Tech companies may have larger profits than manufacturing firms but they fail to hire as many employees as their predecessors.

It is wishful thinking to believe that the economic growth of Big Tech translates to the same kind of job growth that manufacturing firms provided to 1960s America. However, tech leaders have been some of the first to provide possible solutions to this employment gap. Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk have become some the most vocal supporters of Universal Basic Income (UBI). On one stop of his cross-country journey, Mark Zuckerberg posted about how, “Alaska’s social safety net programs are in a way that provides some good lessons for the rest of our country.” Elon Musk has talked about how UBI could help supplement the income of those laid off in the manufacturing industry as automation continues to replace traditional labour.

Moreover, the Big Four have recently come under scrutiny because of their unprecedented market power. For instance, Barry Lynn a fellow at a Google-linked think tank, was fired for his criticism of the tech giant. Google’s executive chairman and Eric Schmidt, was the prominent force pushing for the firing of Barry Lynn, a leading voice for stronger antitrust laws in the tech industry. Barry Lynn wrote that “Google’s market power is one of the most critical challenges for competition policymakers in the world today.” Lynn and his colleagues saw the leanings of the Obama administration as the reason for the Big Four remaining exempt from antitrust enforcement while the European Union fined companies like Google for unfair market practices. This radical perspective which calls for stronger antitrust regulations and enforcement, would be a dramatic departure from current FTC policy. However, proponents of this theory predict that implementing stronger antitrust regulations against tech companies would free up markets and increase growth.

Despite some signs that suggest that Apple and Google are turning into hegemonic monopolies, this comparison fails to take into account a couple of important details. First of all the tech industry is much more competitive than the manufacturing sector, meaning that even with monopolies, large tech giants remain threatened by new competitors. For instance, in 2004, Microsoft made up 95% of the consumer computer market, but by 2012, they only owned 20% of the market. Microsoft serves as an example, that no company, no matter how large, is safe in Silicon Valley.

Second, tech companies remain free from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) enforcement of antitrust laws as long as they don’t exploit the consumer. And for the time being the Big Four have not been exploitative of consumers. Google and Facebook are able to make profits while remaining “free” to all consumers. Amazon’s recent merger with Whole Foods allowed it to cut Whole Foods prices by 30% for Prime customers. If any of the Big Four decided to exploit their power by unfairly raising prices on consumers, they would risk feeling the wrath of antitrust enforcement by the FTC.

It is wishful thinking, to believe that the tech industry alone can meet the needs of the American people as we transition to a high-tech, increasingly automated economy. The U.S.government needs to be assertive as the economic growth from Big Tech fails to reach certain corners of the U.S. At the same time, the U.S.government can’t crack down on the tech industry because it would diminish the benefits that come from these companies. By blocking all mergers between the Big Four and small startups, consumers could lose out on lower prices as evidenced by the recent Amazon-Whole Foods merger. Overall, we need to stop treating Silicon Valley as a golden boy, and start recognizing how even the best industry in the U.S. economy has its limits.

Featured Image Source: Flickr

Be First to Comment