Praying for my friends and family.

Can’t communicate with my family.

I don’t know anything about them, this is desperate. But I trust in God that they’ll be okay.

My sister-in-law follows each Facebook post with a video of the storm. A Miami transplant, she’s luckily away from her hometown in Puerto Rico. But much of her family is not. The wind is blowing. Murky water rises and swishes away houses piece by piece. The camera shakes as a boat takes off. This image, unfortunately, is not unfamiliar. Hurricanes, right before Maria, ravaged Houston, Texas and Miami, Florida. Puerto Rico, though, is different. Puerto Rico is both within the jurisdiction of the United States and without the funding of it, lying in a legal grey area. Now, in the wake of Hurricane Maria, that status — its benefits, its detriments, its durability — matters more than ever.

Puerto Rico is, as a territory, part of the U.S. According to U.S. code the U.S. is defined as “several States, the District of Columbia, and the territories and possessions of the United States including the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.” Because of this, all Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens. However, Puerto Ricans are unable to vote in presidential elections and has a sole congressional representative who is not able to vote.

The U.S. government also has a considerable amount of control over the island. For instance, Puerto Rico is not able to ask the U.N. for disaster relief — even if that U.S. government is failing to provide speedy and efficient relief — since their foreign relations are handled fully by the federal government. The federal government gained even more control starting in 2016 when Congress passed PROMESA (Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act), which established an oversight board for Puerto Rico’s economy to “correct” their massive debt.

The U.S. primarily controls the Puerto Rican economy via taxes. Most people in Puerto Rico do not pay federal income tax. Many would argue that since they do not pay federal income taxes they are not entitled to the assistance of the federal government, including hurricane recovery aid. However, some Puerto Ricans do, particularly the ones who receive their income from organizations based in the states like the federal government. Moreover, the ones who don’t pay federal income taxes pay the federal government via social security taxes, export/import taxes, and commodity taxes. It’s truly taxation without representation.

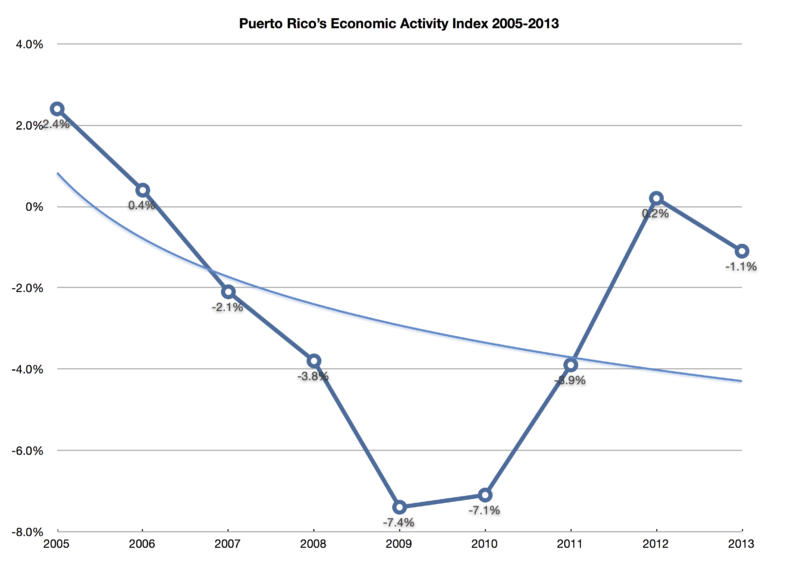

Puerto Ricans also paid greatly when President Bill Clinton nullified a tax break on U.S. mainland companies in Puerto Rico. The tax break had, since the 1950s, brought U.S. manufacturing jobs to the island. Then President Clinton signed a law to phase these tax breaks out over ten years — roughly ten years later in 2006, not only was the Puerto Rican economy crashing, the worldwide economy was about to crash. This sent Puerto Rico’s economy into a tailspin from which it has not recovered. Puerto Ricans did not elect Bill Clinton or the voting Congress Members under him, yet have suffered great consequences at the expense of these public officials.

Additionally, as an island, Puerto Rico is heavily impacted by the Jones Act, “a maritime law requiring shipments of goods between two U.S. ports to be made with American-flagged vessels, manned by American crews.” Puerto Rico, being an island, receives most of its shipments via ports. The Jones Act makes shipments into ports twice as expensive — a huge economic burden to put on an area in an economic crisis that has also been hit by a natural disaster. While the Jones Act was quickly waived in the case of Harvey and Miami, it took massive public and political pressure for President Donald J. Trump to waive the act. Even then he only waived it for ten days.

Due to these discriminatory policies, Puerto Rico’s territory status has stirred up debate on the island and the mainland for decades. There have been five referenda on maintaining territory status, applying for statehood, or declaring independence, since 1967. In the two most recent referenda (2012 and 2017) Puerto Ricans have voted for statehood. It’s worth noting, however, that while 97 percent voted for statehood in 2017, only 23 percent of Puerto Ricans voted. Many protested the vote, saying that it had been rigged by the party in power. Additionally, the support for statehood has been connected to Puerto Ricans’ desire not to become a state but, rather, to shake off the detrimental aspects of being a territory, especially in their current economic position.

But even if every Puerto Rican wanted statehood, would Puerto Rico become the 51st state?

No, because Congress doesn’t want it to be.

As mentioned before, Puerto Rico has a large debt. If they became a state the federal government would have to include that debt in the U.S. GDP. Integrating Puerto Rico as a state would also mean that Congress would lose the incredible control it has over Puerto Rico as Puerto Ricans would get a representative in Congress that could vote in their favor.

Additionally, Puerto Rico wasn’t created to eventually become a state. The 37 states added after the original 13 colonies were given a path to statehood under the Northwest Ordinance. However, Puerto Rico and the other four territories were not added to the U.S. with the understanding that they’d one day become states — they were added to be colonies.

This also goes beyond a political and legal issues — it’s an issue of culture, it’s an issue of race. As Representative Luis V. Gutierrez from Illinois shared in a statement: “The supporters of statehood are selling a fantasy that a Latino, Caribbean nation will be admitted as a state during the era of Donald Trump; that states, many of which supported Trump, will accept a Spanish-speaking state that will receive just as many Senators and maybe even more House seats than they currently have.” Nearly half of all Americans don’t even know that Puerto Ricans are Americans. This can be largely attributed to what Gutierrez points out: Puerto Rico is an island of Spanish-speaking Latinx people, not what you would typically think of when thinking of America. So if Americans hardly know that Puerto Rico is part of the U.S. now, will they accept it as a new state? Probably not.

Puerto Ricans were suffering long before Hurricane Maria hit via the Great Recession and the federal government’s manipulation. This is because they were never meant to be more than a colony, a faraway place meant to benefit the motherland. Hurricane relief has been criticized as severely mismanaged, many singling out President Trump, claiming that he has a bias against Puerto Rico.

In fact, President Trump threatened to rescind emergency responders in a series of tweets. The President even went so far as to blame Puerto Rico’s financial struggles wholly on them even though, as I noted earlier, many of their financial woes were caused by the federal government and Puerto Rico’s limbo status as a territory. Why has he done this? Because Puerto Rico a colony, because the states only want a relationship with it when it benefits us, because it’s an island filled with hispanic people.

As for my family’s Puerto Rican story, my brother was able to get some of his wife’s relatives out of the island and onto dry land. But he was not able to get everyone. He was not able to help the other three million Puerto Ricans, many of whom are living in flooded houses without access to electricity or clean drinking water. Puerto Rico needs to see change of political status within the federal government if it’s going to survive and thrive in the long-term.

Featured Image Source: The United States Department of Defense

Be First to Comment