On September 20th, the people of Nambia were thrilled to hear the president of the United States, Donald Tump, recognize our nation for the inroads we have made against the scourge of infectious diseases. While I am pleasantly surprised President Tump demonstrated awareness of the affairs of smaller states like our own, as President of Nambia, I know that the work small states do often goes unrecognized, unheard, unappreciated. States like ours cannot project power and consequently are more vulnerable to the winds of political change.

Given recent worries about the prospect of multilateral diplomacy and absence of global leadership, the time has come for smaller states to think about ways to shape the international order to be conducive to mutual prosperity, respect, and peace. How can less powerful states exert pressure to become rule “makers” instead of rule “takers?”

The people of Nambia are lucky to have received the recognition we did from president Tump; other smaller nations have to endure humiliating slights that betray powerful countries’ arrogance. At the G20 summit over the summer, the White House mistook Singapore’s president for Indonesia’s. When Prince Phillip made a visit to Australia in 2002, he asked a prominent aboriginal business leader if they “still threw spears at each other,” and in the process brought back painful memories of cultural genocide by white settlers against natives. Faux pas do not necessitate damaged relations — despite the fact that the White House referred to Japan’s Prime Minister as “President” during his official visit, the meeting was largely hailed in Japan as a success. Missteps are often met graciously as the price of engaging in dialogue across cultures. However, a history of arrogance towards a country can lay the groundwork for relatively minor diplomatic incidents to cause major flare-ups that worsen relations.

A 2014 incident in Ghana created one such disruption in relations. The Ghanaian President John Mahama tweeted “As a people, we have had to make sacrifices. I wish to assure you that the results of these sacrifices would begin to show very soon.” The US embassy in Ghana replied on twitter “and what sacrifices are you making? Don’t tell me that pay cut.”

Needless to say, the incident sparked outrage in Ghanaian media during a sensitive debate over austerity measures for an IMF loan. Although the US embassy offered a swift apology, the incident renewed Ghanaian anxieties over perceived attempts by America to meddle in the country’s internal politics. The US embassy’s defense was that the staffer who sent the tweet thought they were using a private handle — an unsatisfactory response for Ghanaians who didn’t want foreigners telling their president what to do in the first place. As a result, the President felt compelled to offer a stern rebuke and many in the Ghanaian media speculated that the “mistake” was no accident — that the US had intended to send that message. Heightened anxiety about American interventionism limited the president’s ability to cooperate with the IMF or America on development goals in the future. This incident would not have been likely to raise many eyebrows had a vocal part of Ghanaian society not already been suspicious of American intentions towards their country. States are understandably suspicious of an ulterior motive in countries that have a history of using their strength to put pressure on countries: high-handedness, or worse: indifference makes such slights more likely to happen and to damage relations when they do.

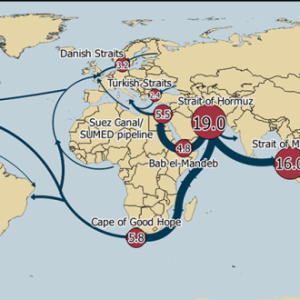

However, the rise of regional powers like China and Russia presents an opportunity for small states to extract better deals from potential patrons. Here, Sri Lanka is instructive. This impoverished, tropical island off India’s coast is strategically located along major supply routes between the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

For years, China built its relationship with the country and poured money into developing its deepwater ports and infrastructure. In return, Sri Lanka offered the Chinese fleet basing rights which it could use to defend the supply routes. However, in 2015, Sri Lankans voted into office Ranil Wickremesinghe, one of the most pro-Western and free market Prime Ministers in Sri Lankan political history. Mr. Wickremesinghe has used this position to increase his leverage with Beijing, threatening to block docking rights for Chinese submarines. This seemed to succeed in extracting concessions — at China’s Belt and Road forum, Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang appeared to offer unilateral aid to develop Sri Lanka’s port. According to Kadira Pethiyagoda, a scholar of southeast Asia, “The larger lesson of Colombo’s [Sri Lanka’s capital] shift to the West is that strategic small states like Sri Lanka now have more options and can easily switch sponsors.” Traditional, Western-backed donors have also found it difficult to attach conditions to aid — and thus take advantage of leverage — thanks to the rise of China. According to Diego Hernandez, an economist, World Bank loans come with 15% fewer conditions for every 1% in extra aid China delivers to an African country. Countries with savvy leaders can navigate between larger states’ interests, and a multipolar world increases the likelihood that any particular state would find itself with multiple potential sponsors. Panama, Kazakhstan, Iraq, Pakistan, Bhutan, the Philippines, and Turkey are some countries that seem to be pursuing this strategy.

Yet playing great powers off of each other leaves small states somewhat vulnerable to forces beyond their control: their bargaining power depends upon having options, but are largely unable to impact how many options they have. If China’s economy tanks, there’s not much Sri Lanka can do to help out and China would no longer be able to provide a counterweight to America or India. China would “refocus” away from a certain set of states to deal with its internal problems. Indeed, China’s long term goals limit Sri Lanka’s importance. China’s One Belt One Road portends a shift in China’s trade away from the shipping routes that pass by Sri Lanka as does the long-term goal of weaning itself off of oil.

Even so, multipolarity spreads the risk of a strategic refocus across multiple potential partners. If China no longer considers Sri Lanka a strategic ally, regional development banks, the World Bank, the US and India would still offer credible alternatives to each other in most sectors. Although their bargaining power would increase after China’s refocus, Sri Lanka’s autonomy to decide for itself which partners give it the most value is never in doubt. This is a radically new global dynamic: During the colonial era, Britain was in Egypt, France was in Senegal, and local residents had no say in the matter. After 1945, the US and USSR were often the only options, and both frequently treated their Third World counterparts as pawns rather than partners. America currently remains the sole global hegemon, and the power dynamic for many states reflects this, but true competitors to US influence are emerging in India, China, Iran, and Russia. The fact that Sri Lanka — one of the world’s poorest states — feels comfortable making demands of its regional hegemon, China, signals a global decentralization of power.

Strong international partnerships help the people of Nambia prioritize their limited resources, and we have appreciated our relationship with the United States. But when a US embassy tweets condescending remarks towards the Ghanaian president or when the American President seems unaware of the existence of a country whose president received a US education, junior partners understandably get jumpy about US commitments and their options in the future.

Featured Image Source: Pixabay commons

Be First to Comment