Following President Trump’s visit to China in his 2017 Asia-Pacific tour, both Xinhua News, the official press agency of the People’s Republic of China, and Trump himself touted his rapport with President Xi Jinping. Yet no sooner had Xi and Trump waxed their platitudes than they were advocating opposing stances on regional trade and leadership in the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation CEO summit (APEC) in Da Nang, Vietnam, on November 10th. In his speech, Trump first reiterated his opposition to predatory trade practices, along with his protectionist “America-first” policy. Markedly shifting away from the traditional terminology, he referred to the Asia-Pacific region as the Indo-Pacific Region. He then promoted ‘rules-based trade policies, freedom of navigation and overflight, including open shipping lanes,’ an underhanded jab at China’s much-contested territorial claims to the small island chains and oil-rich waters of the South China Sea. Trump wagged a cautionary finger at nations seeking stronger ties with China influence by concluding his speech with an allusion to Vietnam’s history as a Chinese vassal state.

On the other hand, Xi defended globalization as an inevitable trend towards a brighter future and encouraged Asia-Pacific nations to resolve territorial disputes amongst themselves. He invited all countries of the Asia-Pacific to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which aims to establish trade and build transport infrastructure from Asia to Africa and Europe, to facilitate mutual economic development.

The conflicting visions of both leaders indicate the persistence of bilateral contention over the leadership of the Asia-Pacific. With his stance on the South China Sea and references to Chinese trade policies and expansionism, Trump’s assertion of containing a troublemaking China was characteristic of his presidential campaign platform and Obama’s Pivot to Asia strategy. Presumably, he meant to affirm that his administration will preserve the spirit of Pivot to Asia. Its ability to do so, however, will be impeded by the geopolitical ramifications of withdrawing the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), compounded by China’s burgeoning economic dominance in the world.

The TPP was a trade pact integral to the implementation of Pivot to Asia. It initially included the United States and its allies Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam. It was engineered by the Obama administration to lower barriers to trade to curb the rise of Chinese market power by reducing reliance on Chinese trade. Under Trump, who was averse to its globalist aspects (e.g. outsourcing manufacturing bases), the U.S. left the pact in January – leaving the remaining eleven constituent nations to redistribute its provisions amongst themselves.

With a GDP that accounted for over 60% of TPP GDP pool, the United States has the highest economic weight as the leader of the TPP. Its withdrawal has led to difficulties for the other countries in balancing interests and responsibilities and maintaining TPP’s standards.

As of early November, TPP agreements have been suspended, as Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, now the leader of the TPP, and Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau failed to reach a consensus on the pact’s provisions on intellectual property. Just by exitting TPP, the U.S. lost the landmark pillar of the Pivot to Asia strategy.

However unpalatable Trump found the TPP, its loss seems significant enough to leave him scrambling for a replacement. In Japan during the Asia-Pacific tour, he and Abe launched the Strategic Energy Partnership for infrastructure development in Asia, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa – regions where China has been constructing infrastructure projects, such as bullet trains, as part of its own Belt and Road Initiative. According to the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, the partnership will provide alternative sources of funding and construction that would provide high-quality, affordable infrastructure projects for countries in these regions. The implication was that the partnership and expertise of two developed countries would yield better growth opportunities for and multilateral ties with developing countries than China, a developing country itself.

The Partnership will likely not be as effective as TPP could have been. Whereas TPP would have mobilized a unified international bloc seeking to reduce economic dependence on China, the Partnership lacks comparable geopolitical leverage and range. The success of projects it initiates in the future greatly depends on the receptiveness of target countries outside of the partnership, not just the collaboration of member nations. This weakness alone will dent Trump’s efforts to uphold Pivot the Asia strategy. Many target countries, such as the Philippines, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Mozambique, and Kenya, experienced Western colonization and exploitation. They are disillusioned with the lackluster political and macroeconomic reforms under Western guidance in the 1980s. They gravitate towards China because they see their relationship with Chinese investment as potentially more egalitarian than with the West’s. The U.S., unlike China, has sufficient historical baggage that may dissuade these countries from allowing substantial aid in the field – thus eroding American influence as China continues to project its global ambitions.

Native Africans find China’s no-strings-attached Belt and Road Initiative a promising engine of mutual growth for all countries involved. A recent study conducted by the Afrobarometer, a pan-African, non-partisan political research network, showed that 63% of citizens from 36 African nations surveyed favored Chinese investment. The Belt and Road Initiative’s investment and infrastructure projects in Africa provide tangible economic benefits to the continent without requiring domestic governments to make large-scale reforms.

For African governments, Beijing’s non-interference policy is refreshing. They had been locked into unproductive business deals with former European colonial powers and the U.S.., who provided billions of dollars of aid in exchange for bureaucratic and social reforms in the legal, private, and public sectors.

Though well-intentioned, these donors prescribed poorly-timed market-based reforms, known as the Washington Consensus, that resulted in skyrocketing food prices, urban poverty, and social unrest. Beijing’s emphasis on economic over bureaucratic and social development gives the impression that it was ready to do business, not to moralize on human rights and democracy while failing to deliver tangible results. As of now, Sino-African ties have increased. Beijing’s 52 diplomatic missions to African capital exceeds Washington’s 49.

Moreover, the globalist theme of China’s Belt and Road Initiative has been appealing to European political elites, particularly Germany and post-Brexit UK, who have been keen on cultivating trade and political relations with China after Trump’s inauguration. As they redirect their faith away from the U.S. in favor of globalization with China, they may view Pivot to Asia as an obstructive force against their nations’ access to the massive Chinese market. Thus, their support for containing China will wane, limiting the range of international alliances the United States can construct in implementing Pivot to Asia.

Though we have another three years to see how the Trump administration will continue to pursue Pivot to Asia, it is apparent that doing so will not be easy. Trump’s fixation on protectionism and his withdrawing the U.S. from TPP has undermined, if not downright sabotaged, the Pivot to Asia Strategy the Obama administration had formulated. As Chinese investment and goods becoming increasingly attractive to its historic allies, one thing is for certain – the United States will need to consider winning over new players to help implement Pivot to Asia.

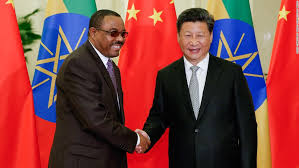

Featured Image Source: scmp.com

Be First to Comment