The December midnight was drenched in silence. A large crowd stared on from the harbor as the Sons of Liberty crept along the docks in Mohawk Native American costumes. They swept through the streets of Boston with one pursuit in mind: dump the coercive British tea. With the quiet punctuated only by the sound of tea crates slapping the water, a rebellious patriotism that has come to define American politics was born.

The American Revolution was catalyzed on the notion that minority voices should not be drowned out by those with a monopoly on power and representation. The call for “No Taxation without Representation” rang out through the streets of New England. In his famous contributions to the Federalist Papers, James Madison declared the need for a strong government that could proscribe “the mischief of factions,” wherein certain political parties or interest groups could wholly dominate and silence minoritarian voices. As a result, the Constitution aimed not only to prevent dictatorship, but also impede the tyranny of the majority. How is it, then, that within contemporary American politics, the two major American parties have left so many feeling unheard?

The modern Tea Party movement began in 2009, when conservatives decried the excessive taxation and government intervention they felt had occurred under the Obama administration. They called for an end to such policies and demanded stronger limitations on immigration. Tea Party advocates came to be defined by relative extremism and an anti-establishment mantle, not only against the Democrats in power, but also against fellow conservative Republicans, who boasted a more centrist agenda. Beginning as a small, fringe disapproval of entrenched politics and big government, the Tea Party movement swelled into an unencumbered political outcry, with big-name supporters like the Koch Brothers behind its goals. Building on its momentum, the once-fringe movement was able to successfully destabilize majoritarianism in the Republican party. Tea Party Republicans kicked up such a storm that John Boehner, then Speaker of the House, stepped down from his prestigious position. Tea Party-ism capitalized on disillusionment with the inefficiencies of an interventionist big government and claimed, to much applause, that the Republicans and Democrats alike were failing to adequately represent their constituents’ interests.

Many Democrats laughed off the movement, perhaps enjoying the internal turmoil of their Republican rivals. In a segment called Tempest in a Tea Party, comedian Jon Stewart commented that the movement was, “like the Boston Tea Party for people that decided, let’s say two-and-a-half months ago, that they didn’t want to pay taxes anymore.” Yet the peripheral movement became less amusing when it played a large part in shutting down the government for two weeks in 2013. An annoying, fringe movement no longer, the minority anti-establishment coalition claimed a strong voice and made themselves heard. Now, it is the Democrats’ turn to join the mad Tea Party phenomenon.

In April of 2016, President Obama warned law students against Tea Party-ism, condemning the attitude that, “We are just going to get our way, and if we don’t then we’ll cannibalize our own, kick them out, and try again.” It seems he feared a party split, similar to that which the Republicans experienced, that would cleave the country and shatter his legacy. Much of this is thanks to the surprising success of Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders, a self-proclaimed socialist democrat, who championed an almost revolutionary progressive platform, touting free public college and a higher minimum wage as key components of his candidacy.

Despite his modest beginning as a relatively unknown candidate, Sanders swept up many voters who felt disenfranchised by the Democratic establishment. And although the Clinton brand name was familiar to most Democratic voters, Hillary Clinton’s campaign failed to inspire and capture the millions who ‘Felt the Bern.’ This was, at least in part, attributable to growing distaste for American political dynasties that felt a little too close to quasi-monarchy and outright nepotism. Bernie represented a break from an establishment that many disillusioned voters could rally behind. His ideas were entertaining, and his policies didn’t sound like a grocery list of traditional Democratic positions. For many voters, having been made to feel like minorities in their own party, it was only logical that they seek a candidate who claimed that he could give them a voice.

This cleavage has become especially prominent in California, a bastion of Democratic power. On Sunday, October 15th, California State Senate President Pro Tempore Kevin De León announced his run against incumbent U.S. Senator Dianne Feinstein. Senator Feinstein drew sharp criticism at a town hall in August of 2017 when she asked voters to be patient and suggested that Trump could be a good president if given enough time. De León quickly fired back that, “It is the responsibility of Congress to hold him accountable, especially Democrats, not to be complicit in his reckless behavior.” And so the Democratic cleavage exploded in California politics, with Feinstein representing reconciliation and tolerance and De León representing a refusal to compromise on progressive ethics.

The battle between the two powerhouses is not really about policy; it’s about the symbolism of the candidates. Feinstein is the oldest U.S. Senator and has served in the U.S. Senate for 25 years. De León is a younger, fresher face, seemingly able to bring much-needed new blood onto the Senate Floor. He entered the race knowing full-well that polls suggested an easy win for Feinstein, as they still do. Politico cited a Berkeley IGS poll showing that De León was polling at only 3% in April of 2017. Keenly aware of his pollster shortcomings, De León stated that the race, “will be David and Goliath…I’m under no illusion.

De León, it seems, is trying to ride the “Bernie Bros” wave, and transform himself into everyone’s new favorite underdog. Comparing himself to David is De León’s method of saying that only he can represent the unheard voters who have been neglected by Feinstein, California’s [implied] resident Goliath. However, De León is not an exemplary model of a Bernie Sanders underdog wave. In the 2016 election, De León endorsed Clinton, not Sanders. His self-identification with David may be more about capturing minoritarian voices than it is about actually representing them. But still, he has positioned himself as further to left than Feinstein, making firebrand remarks that disavow what he sees as a moral compromise. In calling out Feinstein on her request for “patience” with Trump, he made clear that many of voters are sick of being patient. His candidacy, while not a revolution in the way Sanders’ was, does represent a split in the previously unified Democratic party establishment.

The problem is not that Feinstein is doing a poor job of representing her constituents. Having more candidates in the field means that politicians have to be more attentive and responsive to their constituency — they are not allowed the luxury of a comfortable position. One of the central tenets of a functional democracy is competition. When incumbents are able to run unopposed for years and years on end, it may signal a breakdown of the anti-faction, anti-majoritarian nation which Madison imagined. And while De León may have slim-to-none odds of winning, his campaign very well may encourage Feinstein to reassess her politics.

California Democrats are now faced with a serious question about their party: reconciliation or refusal? It’s not just theoretical blathering or campaign politics. The elected candidate will be going off to Washington, where he or she will be faced with a Republican majority Senate hell-bent on reversing Obama-era projects, cutting expensive social welfare programs, and fighting for traditional viewpoints. Feinstein has a history of working across party lines. She has the political know-how to perhaps nudge her Republican colleagues a little more to left. California Democrats have to choose if they want to compromise on unfavorable Republican bills or push for hardline progressivism. The latter risks inspiring the kind of congressional gridlock that reared its ugly head under the auspices of Tea Party politics in the second half of Obama’s presidency.

But that outcome lies in the future. For now, the question remains: are Democrats engaging in a kind of “tyranny of the majority” within their party by trying silence and squash the progressive, Bernie-esque camp? Perhaps it’s time for Democrats to seriously interrogate the reasons for divide and seek improvement, instead of hoping that status quo politics will save them in the next election cycle. The Tea Party movement faded away, but Republicans are left with the bitter aftertaste of internal division, as Mitch McConnell and Paul Ryan duke it out with a populist president. Ultimately, this debate of division begs a basic question about the legitimacy and durability of American democracy. Can the two-party system genuinely benefit all American voices, or does it impose a majoritarian suppression of political minorities? If oppression is endemic, voters may have to join the Mad Tea Party to make their voices heard.

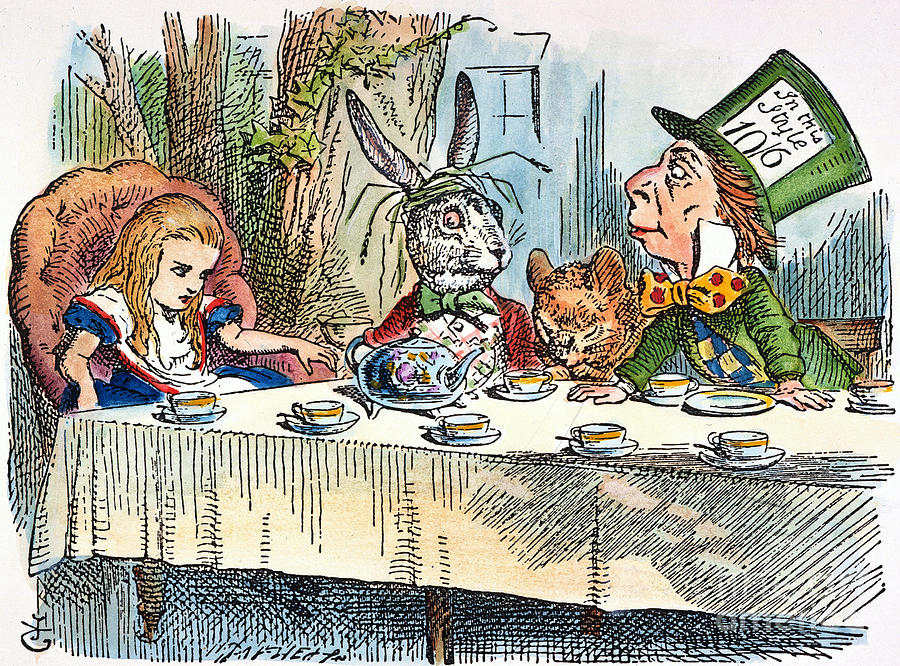

Featured Image Source: Fine Art America

Be First to Comment