China’s rise as a world power has been comprehensive to say the least. Alongside its growing powerhouse of an economy comes its political ambitions to assert dominance. Nothing new, one would assume. However Xi Jinping’s soft power initiatives in Africa, Latin America and most importantly, in his own backyard, Asia, show a shift in the extent of aggression with which political influence is hoped to be achieved. China has attempted to lead by example, proving to some world leaders the suitability of the Chinese Model. Concerns over the undemocratic and illiberal nature of this model continue to surround debate. But on this front, Asian developing countries have arguably little to lose.

The Chinese Dream

Xi’s announcements at the Chinese Communist Party’s highly anticipated congress in mid-October of 2017 drew the curtain on China’s hopes. Along with revealing the new Politburo committee, Xi spelled out his own vision for China- The Chinese Dream. The Chinese Dream can be characterized by a stronger push to improve Chinese soft power and the narrative China presents to the rest of the world. With Xi’s acknowledgment of their miraculous pace of economic growth and development, he saw an opportunity to transform China’s political standing. The Chinese Dream is a move to establish China as a leader in the developing world.

For years, political scientists have shown caution on the topic of China’s rise. Western Liberalism has by far enjoyed the most economic and political legitimacy on the international stage. However, China’s resistance to the liberal, capitalist world order threatens this. China has established its own route to a seat at the table as an alternative for developing states.

The Chinese Model

The million-dollar-question would appear to be: what does this route entail? China’s growth model, or the Beijing Consensus, calls for an increase in economic trade and relations while keeping a tight grip on domestic affairs. It keeps the government in strict control of all aspects of social, cultural and political life while providing some leeway for the economy to function liberally. China’s high economic growth has been viewed as causal of, but also contingent on, the strength of its centralized government. If we look at the facts, China’s authoritarian tendencies have led to efficiency and cooperation in judicial and political aspects of economic activity.

As all things do, China’s method of development has its pros and cons. The loss of democracy and infringement on human rights are often cited as major disadvantages to the model. Civil rights groups and politicians across Asia have remained vigilant of Chinese influences for these reasons.

Human Rights

“There’s no river there,” he says. The soil’s no good, either, he says: “You can’t grow anything, so how will I survive? How will my family survive?”

– ‘’I Will Lose My Identity’: Cambodian Villagers Face Displacement By Mekong Dam’ by Michael Sullivan

Since 1994, China has invested 14.7 billion USD in Cambodian infrastructure, agriculture, and industry. China has been heavily involved in solving Cambodia’s electricity deficit, yet with very ‘Chinese characteristics’. A Chinese company owns 51% of a hydroelectric dam project in North Eastern Cambodia. The construction of the Lower Sesan II Dam would help increase electricity availability for the benefit of the Cambodian people and economy, but with notable costs. The project has disrupted the lives of 5,000 families who are to be forcefully evicted. As well as 40,000 locals who are dependent on fishing for sustenance.

Yet, this is an explicit example of the Chinese way. Strong pushes by the government to develop infrastructure and economic capacity, accompanied by disregard towards the individual rights of people. This incident is far from isolated. It exists as a model for growth that is continuously being exported by China in exchange for influence.

Democracy

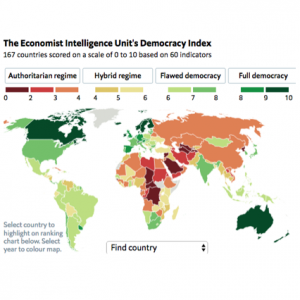

The theory of modernisation posits that developing countries will move towards democratisation once they achieve a certain level of economic growth. China is nowhere near democracy despite its sustained 9% growth rate. In fact, a move towards democratisation could hurt the economy. And the Chinese government’s legitimacy would mirror the plummeting growth figures it relies so heavily upon. Democracy in China is a risk not worth taking. Furthermore, one can question the role of inertia in informing the widespread belief in this Western narrative of development.

While it may not be ideal, it is important to consider the contexts of developing democracies. Poor infrastructure, corruption, long legislative procedures act as disincentives and bureaucratic nuisances to investors and subsequent growth. Take India for example. India staggers significantly behind China, despite being in similar positions a decade ago. New Delhi’s decentralized power, corruption, and vulnerability to opposing interest groups have made infrastructure development a nightmare. India doesn’t possess the autocratic privilege of concerting the economy in the face of ever-growing opportunity costs. In contemplation, Indian democracy can be seen as a burden rather than an aid to development and poverty alleviation.

However, these timeless debates on the value of democracy fail to address an underlying assumption- how much democracy exists in the first place for it to be defended? Democracy requires an informed populace to exercise their suffrage to influence economic, social, political and legislative outcomes. India, like many other democracies in Asia, faces an increasingly apolitical population. While many point to literacy and awareness as causes of this, research has shown that even the educated, middle to upper socioeconomic groups in India have poor political participation.

However, these timeless debates on the value of democracy fail to address an underlying assumption- how much democracy exists in the first place for it to be defended? Democracy requires an informed populace to exercise their suffrage to influence economic, social, political and legislative outcomes. India, like many other democracies in Asia, faces an increasingly apolitical population. While many point to literacy and awareness as causes of this, research has shown that even the educated, middle to upper socioeconomic groups in India have poor political participation.

Image Source: https://infographics.economist.com/2017/DemocracyIndex/

I would like to make it clear, however, that I am not arguing along lines of essentialism. I do not agree with the idea that Asians are naturally more prone to authoritarian regimes or that they are not made for democracy. Democracy is difficult to build, and thus, attain. Many developing countries in Asia have extreme levels of poverty, illiteracy and weak institutions that inhibit democracy from flourishing. With this in mind, deprioritizing an already ailing democracy and pushing for economic growth through strong government initiatives, can be very appealing.

The once ‘Sick Man of Asia’ has established itself as a postmodern role model. While this article only touches upon Cambodia and India, China’s soft power reaches are far and ever expanding. Their ‘message’ to the developing world includes their not-so-secret ingredients of illiberalism and centralisation. China’s significant investment has been accompanied by an increased manipulation of local politics and a diminished value for human rights. Yet, this doesn’t deter quasi-dictatorships like Cambodia or growth-hungry democracies like India. That said, the Chinese Model is here to stay and Asia is set to follow.

Featured Image Source: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1143954/just-what-xi-jinpings-chinese-dream-and-chinese-renaissance

Be First to Comment