Democracies are built on the backs of ideals. As democracies get stronger, so do the institutions and ideals they are built upon. However, the international community has recently seen even the most resilient democracies fracture under the weight of anti-democratic forces. Take India and Turkey as examples, where strong-arm leaders have gained control, and have made their countries increasingly authoritarian. Even the United States, a self-proclaimed beacon of democracy, has borne the effects of a self-aggrandizing leader constantly engaged in spats with federal and state institutions. This development shows how quickly hard-earned progress can be lost, and what happens when democracy is taken for granted.

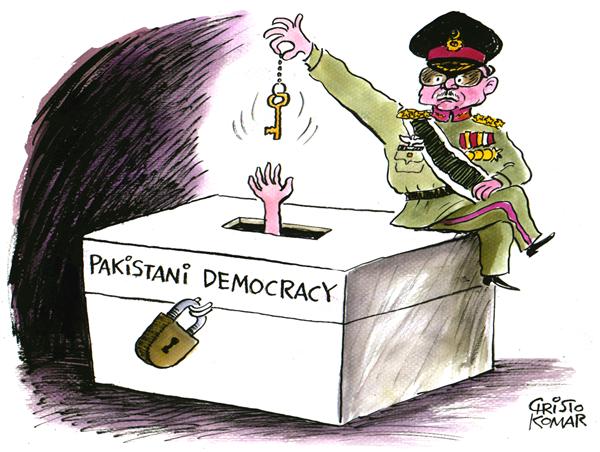

Pakistan, a relatively young democratic country with merely seventy years of existence, has seen nothing but instability in its political climate. The military sector has constantly meddled in its national politics, justices have been accused of political bias and extremist religious factions have influenced public opinion and policy-making for way too long. In light of this, is it fair to say that the upcoming general elections are going to be representative of the will of the people, i.e. truly democratic? In appearance yes, because majority votes will elect representatives to Parliament. But in reality, not really. Major political parties are embroiled in their own existential struggles while the judicial and military sectors are under constant fire from people unhappy about their outsized role in politics. With a void of ideas and an assault on institutions, democracy in Pakistan is under threat, which will bring in question the legitimacy of the upcoming general elections of 2018.

Usually, it is a sign of a healthy democracy to have multiple parties in the political mainstream. With an abundance of parties, tackling issues from various angles and presenting the public with options, comes an abundance of ideas. This is what the New York Times columnist David Brooks refers to as the “abundance mindset.”

“Democratic capitalism provides the bounty. Prejudice gradually fades away. Growth and dynamism are our friends…the abundance mindset is confident in the future, welcoming toward others. It sees win-win situations everywhere.”

In Pakistan however, there is a clash of personalities instead of a clash of ideas. When there is no meaningful policy to win support, politicians play with people’s emotions and rally them to their grandiose causes by evoking fear and hatred against the ‘other’. Consequently, leaders create a divisive atmosphere leading to mistrust among fellow citizens. No one in Pakistan plays this game better than the religious factions.

Just recently, the religious group Tehreek-i-Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah (TLYRA) gained national prominence by staging a major sit-in in Faizabad, where they protested the softening of anti-blasphemy laws and demanded the resignation of Pakistan’s Law Minister Zahid Hamid. The protest turned violent and resulted in the killing of one police officer. TLYRA’s leader, Khadim Hussain Rizvi, rose to prominence back in 2011 after he threw his support behind Mumtaz Qadri, a security guard who killed Salmaan Taseer, the Governor of the Punjab province. The stance cost Rizvi his job in the Punjab government. There was a great outcry from the public, but Rizvi justified his support for Qadri saying Taseer had labeled the blasphemy laws “black law”. His vehement support for this cause has earned him the nickname “blasphemy activist” in religious circles.

On October 26, 2017, TLYRA contested local elections in the city of Peshawar and managed to come within a 2.5 percent vote margin of the Pakistan Peoples Party. PPP was once considered the harbinger of strong democratic values in Pakistan and even though it does not stand at the same pedestal in public conscience as it once did, it still represents a progressive brand of politics. The very same dynastic PPP is now standing neck and neck with religious parties like TLYRA in certain parts of the country. Whether this result becomes a nationwide phenomenon is yet to be seen, but TLYRA has etched itself in public political discourse by religious exploitation.

In his article, Brooks mentions a scarcity-mindset where religious factions turn from faith to “siege-mentality interest groups.” This is increasingly true in Pakistan, where religious leaders have opted out of their role as scholars and interpreters to become leaders who bank on people’s religious views to garner votes. Apart from undermining democracy by suppressing diverse views that might fall outside the confines of religion — as these parties interpret it — this can create dangerous situations, a snapshot of which was already seen in the Faizabad sit-in.

The current ruling party (the Pakistan Muslim League-N), which is poised to win this year’s general elections, has spent the last year undermining the integrity of the Supreme Court after it disqualified the party’s leader — Mian Muhammad Nawaz Sharif — from his post as Prime Minister based on allegations of money laundering. Party representatives, including Sharif himself, have come out in staunch opposition to the Supreme Court, alleging the military influenced the court, which shaped the disqualification decision. Sharif characterizes the court as having “dual standards”, and being determined to punish him at all costs, thereby predetermining the decision against him. In one particularly shocking case, a PML-N senator even threatened the court outright.

“You are on duty today. Remember, you will be retiring tomorrow. We will make your life and [those of] your family members miserable in Pakistan,” senator Nehal Hashmi says targeting judiciary members probing Sharif families’ ties to offshore companies.

It is one thing to question the reasoning of a case (which by all means the reasoning behind the Panama case decision was very questionable), it is an entirely different thing to rile up an entire nation against the premier justice provider based on unsubstantiated claims. Sowing mistrust in institutions only serves to undermine civil discourse by creating a divisive atmosphere

The military has also played a central role in undermining democracy in Pakistan over the years. Election manipulations have been periodically exposed, as demonstrated by the Mehrangate scandal that took place during the 1990 elections. The scandal revealed vast sums of money being disbursed to political parties at the behest of then Army Chief Mirza Aslam Beg. Nawaz Sharif, who won those elections and became Prime Minister. He is alleged to have accepted 3.5 million rupees ($35,000) from the sum amount. The military has also staged multiple coups, ousting democratically elected leaders and setting the country back each time. To date, Pakistan has spent nearly half of its existence under military rule, with the first takeover happening a mere eleven years after the country came into being. Military antics have been a disaster for Pakistan, where democracy has not even been given a chance to flourish. Although the military has accepted a more subdued role in the current administration, their relationship with the civilian government is still choppy at best. This time, however, the trouble is coming from the civilian end more than the military, as Nawaz Sharif has taken it upon himself to blame the military — which has helped him get elected in the past — for having an overreaching influence on the judiciary. The hypocrisy is pretty obvious.

To establish faith in democracy, it is absolutely essential for the public to know that their civil rights and liberties will be protected by judicial institutions, against societal harm. In Pakistan, however, the image of the Supreme Court has been adversely affected because of its highly dominant role in some of the most politically charged periods in the nation’s history. The court legitimized all three military coups in 1958, 1977 and 1999 under the “doctrine of necessity.” Such actions give political parties an excuse to attack the court’s integrity by highlighting double standards where civilians are given harsher punishments than the military. More recently, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Saqib Nisar visited Mayo Hospital in Lahore to review the quality of healthcare provided to patients. After discovering a lack of clean drinking water provided to patients, he ordered relevant authorities to install a filtration plant. His actions drew immense criticism from media which attacked him for confusing his role with that of an elected representative of Parliament.

Salman Masood, Pakistan Correspondent at New York Times wrote on Twitter: “Curious to know under which constitutional provision Chief Justice is required to visit hospitals or any other public buildings, and issue orders.”

Obviously, it does not help when hardly any elected representatives visit hospitals to perform the job Justice Nisar took upon himself. Moreover, there is a huge backlog of cases within the judiciary. Justice Nisar blames the Parliament for not enacting proper legislation, causing judges to perform their job ineffectively. Being critical of other branches of government and overstepping its bounds has left the Supreme Court in a precarious situation where the public is stuck between having to rely on the courts, but unable to fully trust them to provide justice. An article in Pakistan’s daily newspaper reported: “In most civil and revenue matters, the litigants have to wait decades — sometimes the third generation of the petitioners get the final verdict in their cases.”

I mentioned earlier that political parties, instead of presenting actual reforms to the public, have instead embroiled themselves in a clash of personalities. Blame games are rampant and finger-pointing is the rallying call. The aftermath of the Panama case, the exploits of the judiciary and the immaturity of the opposition all stand as mounting examples of this. In the current heated climate of “he did, she did”, it is difficult to judge who holds the key to our economic and social progress. It is true that the Pakistan Muslim League (N), which has been in power for five years now, has upscaled infrastructure and improved the economy. One of its defining achievements has been the investment and development brought about by the China Pakistan Economic Corridor. But ever since their leader was disqualified by the Supreme Court in the Panama case, they have relied on criticizing every person, party, and institution that crosses their path. In the current climate of agitation politics, the ruling party has demonstrated irresponsibility in uniting the country in tumultuous times. Driving a rift between different branches of government has damaged the public trust in democratic institutions and created an environment where opposition groups are growing increasingly intolerant of each other.

Fareed Zakaria, a columnist for the Washington Post, describes the problem facing the world today as “illiberal democracy” — elected governments that systematically abuse their power and restrict freedoms. In his recent column in the Post, Zakaria said institutions are collections of rules and norms agreed upon by human beings. The character of democracy will weaken if these leaders attack and denigrate these rules. An established democracy like the US was rated a “flawed democracy” for the second consecutive year on the Economic Intelligence Unit Index. So it should not come as a surprise if Pakistan, where anti-democratic forces are constantly tugging and pulling at the state of affairs, is rated a “hybrid regime” on the same index, falling between a democracy and an authoritarian regime.

Featured Image Source: Vivify

Be First to Comment