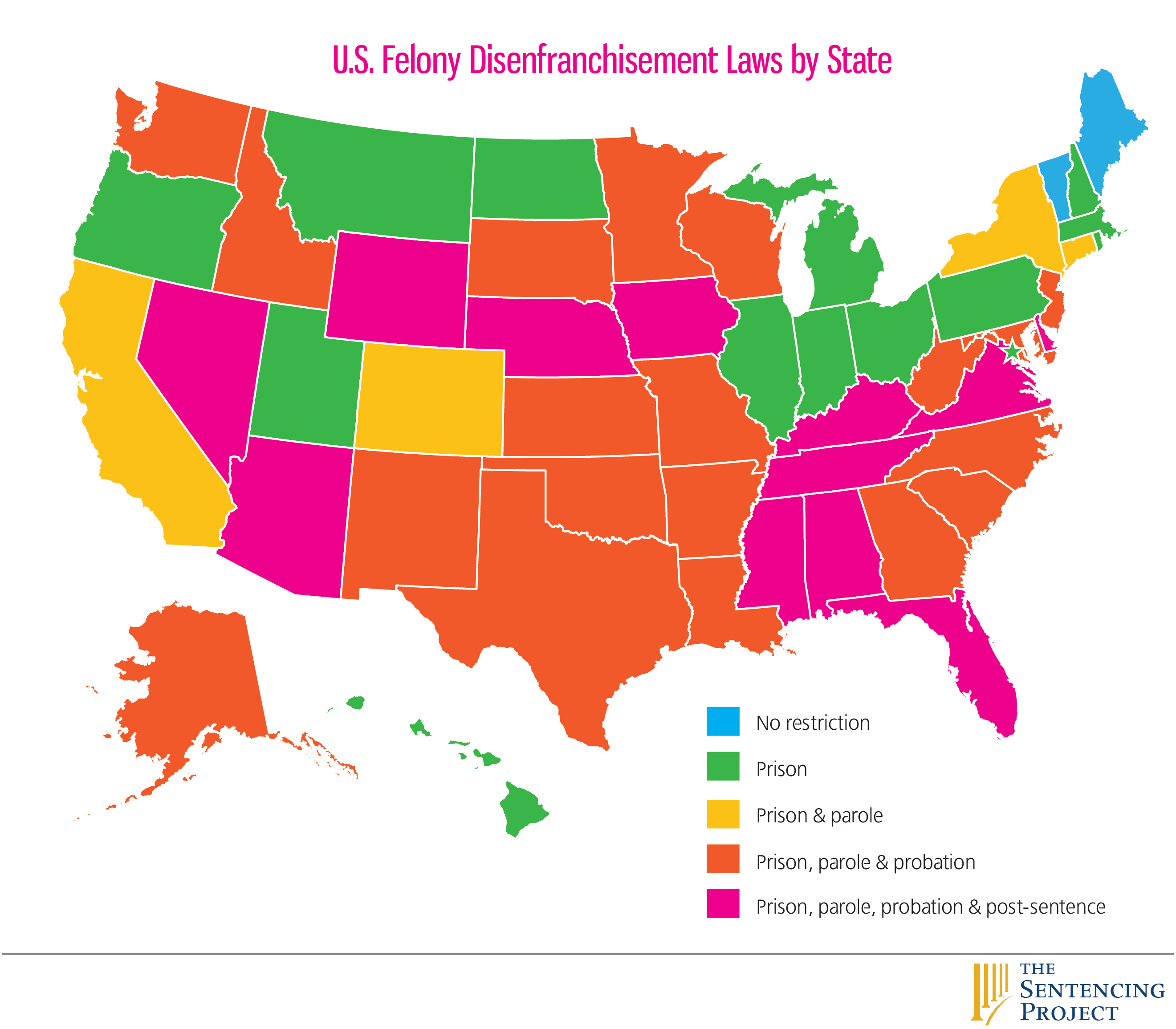

Six million American adults are legally ineligible to vote, members of a group whose ranks have roughly quintupled over the past 40 years. In Kentucky and Tennessee, this group now comprises more than a fifth of the African American population; in Florida, this group composes more than 10 percent of the adult population. But these states merely dramatize a larger phenomenon: nationwide, 48 states prevent certain citizens from voting. Why? They have felony convictions.

Lately, rulings and ballot measures — including Florida’s upcoming Amendment 4, which would constitutionally restore the franchise for life to hundreds of thousands of felons — reflect the growing consensus the states’ felon disenfranchisement laws have gone too far: according to the Prison Policy Initiative, “the U.S. justice system controls more than 7 million people,” most of whom are on probation. In states where the franchise can be restored by the governor’s personal pardon, the New York Times reports that “in the last few years, Terry McAuliffe, as Virginia’s governor, restored voting rights to more than 168,000 people, and the governors in Kentucky and Iowa granted roughly 9 in 10 of the restoration requests they received in the first half of the decade.” These executive actions reflect a growing movement to correct the overreach of our criminal justice system.

Felon disenfranchisement is old news in America — laws barring some felons from the polls have existed for 150 years. Historically, challenges to state felon disenfranchisement laws have foundered at the Supreme Court, but the legal basis for the fight is unusually ambiguous because the constitutional basis for felon disenfranchisement, Section II of 14th Amendment, performs an odd legal trick: for the purposes of Congressional representation, Section II says that anyone denied the right to vote based on “participation in rebellion, or other crime” shall be nonetheless counted. So the Constitution implicitly condones felon disenfranchisement without explicitly legislating anything. The “constitutional” defense of felon disenfranchisement laws is certainly clear given the technical, precedent-oriented nature of jurisprudence.

But even if such technicalities suffice in a legal sense, the real question is not about what the Constitution establishes, for the Constitution can be amended (indeed, felon disenfranchisement appears to be an afterthought in one such amendment). The real question is whether America should exclude any of its citizens from the democratic process; the quandary is moral, not technical.

And felon disenfranchisement laws have only gotten worse in recent years, with increasingly profound consequences for certain populations; indeed, some felons can vote, but those who cannot are disproportionately people of color and the poor. And that’s no accident. According to the Brennan Center for Justice, after the Civil War, “two interconnected trends combined to make disenfranchisement a major obstacle for newly enfranchised black voters. First, lawmakers — especially in the South — implemented a slew of criminal laws designed to target black citizens. And nearly simultaneously, many states enacted broad disenfranchisement laws that revoked voting rights from anyone convicted of any felony.” As the documentary, The 13th and efforts like The Sentencing Project observe, targeting felony convictions as a proxy for a race gives political cover to politicians seeking to disenfranchise Latinos or African Americans.

The racial implications of felon disenfranchisement have obvious political overtones: People of color lopsidedly favor Democrats, and many states who limit felons’ voting rights are in deep-red Appalachia and the Deep South. But the issue isn’t neatly partisan. Massachusetts voters (not famed for conservatism) amended the state constitution in 2000 to disenfranchise incarcerated felons, and in 1997, then-Texas Governor George W. Bush signed a law “eliminating the two-year waiting period after completion of sentence before individuals can regain their right to vote.”

But partisan or not, the issue is absolutely political — politicians across the country and on both sides of the aisle have for decades campaigned to appear “tough on crime,” although the issue has certainly waned as crime has plummeted from its peak in the mid-1990s. We are, however, witnessing a resurgence of anti-crime posturing, albeit with vintage language: the president campaigned during the 2016 cycle about restoring “law and order” — a perhaps unwitting use of rhetoric favored by Richard Nixon in the late 1960s — rather than regurgitating the Reagan/Clinton era lexicon. Much of the impetus for felon disenfranchisement policies has involved political calculations that being “tough on crime” had good optics, and disenfranchising felons offered politicians a way to appear grave and resolute about punishing criminals without escalating the already draconian mandatory minimums and exceptionally long sentences increasingly being enacted.

Irrespective of politics, however, states’ handling of felon voting rights is, from a legal perspective, exceptionally arbitrary and somewhat constitutionally dubious. Alabama, for instance, includes sodomy and possession of marijuana under its definition of “moral turpitude” for which felons are disenfranchised. But it also includes murder, manslaughter, and rape. Implicitly, Alabama law conflates the severity of minor drug convictions with first-degree murder, an absurd equivalency which highlights pervasive arbitrariness in such laws.

In contemporary debate, defenders of felon disenfranchisement laws will note that in some states (albeit mostly those with the smallest black populations), the felon population largely comprises older white men — a largely conservative demographic. They argue that if some states are disenfranchising likely Republican voters — and moreover, predominantly white voters – that the system cannot possibly be racist or biased against Democrats. By contrast, liberals respond that voters of color are nonetheless disproportionately incarcerated, even if they represent a minority of disenfranchised voters. And progressives also contend that in addition to being anti-Democratic, felon disenfranchisement is also deeply anti-democratic.

Perhaps some convicted of felonies — those guilty of extremely violent crimes, for instance — have truly gone beyond the pale. But most of those people will walk free again. They will hope to lead normal lives. They will hope to atone and be forgiven. And they will want to be part of a society that now appears to want no part of them. In short, they will be at the mercy of a merciless nation – one which favors punishment over restraint, where the “justice” system has reinvented injustice.

If America is to remain the land of the free — the birthplace of modern democracy — it behooves us to choose rehabilitation rather than retribution. If they have served their time, people deserve to participate. If they have not harmed others, former felons should regain the franchise. Certain crimes — murder, terrorism, treason — may trespass too severely on our morals. But most Americans who are locked up should not be locked out of democracy — especially not its most profound and precious civic duty.

Featured Image Source: The Sentencing Project

Be First to Comment