It seems odd to juxtapose “environment” with “refugee”. The environment is a set of conditions that cultivate the life of beings. By definition, it is suited to the livelihoods of certain humans, just as humans are suited to their environments. Both participate in a symbiotic relationship, so the term “environmental refugee” indicates a very unnatural association. But that is what Shuahi Linxiang – one of the 1.3 million people forcefully moved in the development of the Three Gorges Dam, is – an environmental refugee.

An environmental refugee is a person “forced to leave their traditional habitat temporarily or permanently because of an environmental disruption.” While this can be due to natural occurrences, since the 90’s there has been a rapid growth of development-induced displacement. Development can refer to the “process of converting land for a new purpose” , or structural development. Many times, this is to counter the harms previously caused by people, such as the development of the Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary in India. Thus, it is not that structural development itself is innately harmful. Rather, development-induced migration is due to structural development superseding political development. The inaction by the international community has also largely exacerbated the issue.

Three Gorges Dam

Shuahi Linxiang, a 57-year old woman, was one of the 20,000 people relocated from Huangtupo during the 1998 wave of forced migrations. “If the government says you have to move, you move,” she says. “We can’t oppose them.” From 1998-2012, around 1.3 million Chinese people were relocated to make space for the construction of the Three Gorges Dam which would help to supply more energy to meet the large demand. The dam started to function in 2012. Analyzing the effects of this construction can show the negative impact that development can have, which is important in recognizing as we move towards more development in the future.

While the dam provides around 3% of China’s energy, it has caused irreparable damage to the lives of individuals who were forced to move. Many displaced individuals were stuck in tents, and their homes destroyed during construction or in the wake of a landslide. The loss of property rendered many people with little to no assets. The government promised some amount of compensation, which may have offset some of the damages caused (it is not known what this amount is.) Yet, the government’s promise remains largely unfilled. More than 20 years after construction began, people are still protesting to receive their amount in compensation. Wu, one of the 500 people relocated to the megacity Chongquing, said, “we made complaints, and the police told us to go home…when we got home, nothing was done, even though the Three Gorges Committee knows about our situation.”

With more than 180,000 protests a year in China, McLaughlin argues that “demolition and forced relocation are the biggest flashpoints for social unrest in China.” Ultimately, these “flashpoints” are indicators of structural violence. The state is committing structural violence, a form of invisible violence which is embedded in the politics, practices, and institutions. Structural violence is also normalized and not questioned by the people. It is seen in Shuahi’s statement of the forced migrations: very few people questioned the position they were in, and those who did protested after they were forcibly moved. It seems that the Chinese state does not feel an obligation to fulfill their promises to their people. Many representatives and local bureaucrats simply don’t care and aren’t held accountable.

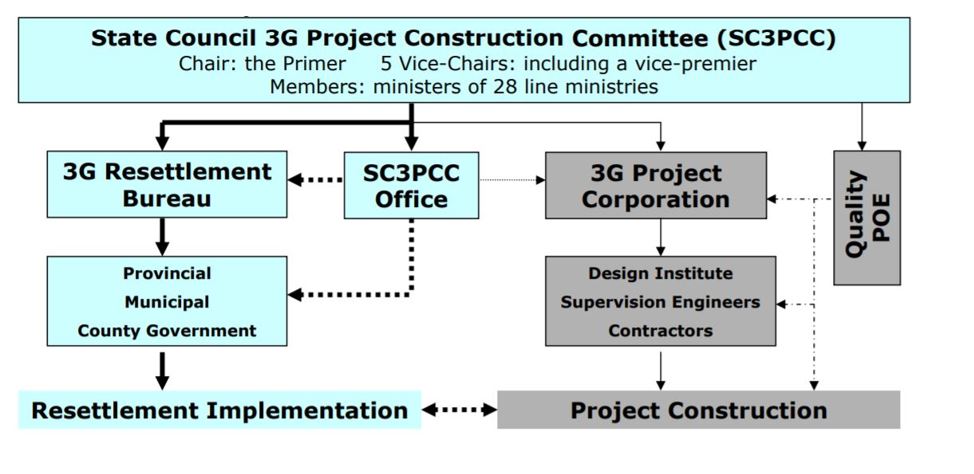

This form of “structural violence” is partly rooted in undemocratic political institutions. A strong political institution is characterized by full accountability and responsiveness to the people. This is not to say that democracies have no structural violence, but democratic institutions tend to allow for more accountability from the government. China has an authoritarian government which makes it likely that weak institutions will follow. This might be because of the indirect and complicated relationship between local officials and the larger Three Gorges Committee, which is part of the state council. For the cries of the people to be heard by powerful officials, it needs to go through multiple levels of government. Even if these concerns were heard, there is no guarantee that change will occur.

The institutions are ill-equipped to respond to the concerns of the people. For instance, the United States’ constitution has an “eminent domain” clause which outlines the fundamental rules when the government needs to take private property: most importantly that the government must provide “just compensation.” There are many accountability issues with the legal system in the US, but if a person is not satisfied by the provisions offered by the government, it is possible to file a lawsuit and bring the case to the courts. There is little form of recourse for the displaced people in China and no guarantee for a “just compensation.” When such institutional and economic development moves forward without much political development, it creates a larger discrepancy between urban and rural people and increases socioeconomic inequality- so, the cycle of structural violence continues.

Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary

Wildlife Sanctuaries have been India’s primary method of conservation. The efforts at conservation are commendable and highly needed. However, they are not without cost. The lion reintroduction program has resulted in the relocation of 24 villages and over 5000 people. Similar the to the Chinese government’s promise made during the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, the Indian government promised these villagers compensation. They promised funding of plots, as well as the provision of irrigation facilities. While the government was able to fund plots, there was not any surplus for the latter. As economist Asmita Kabra states, “This leaves the government in a situation where it has promised irrigation facilities to the displaced community as part of the relocation package but is unable to finance it from the budget allocated to it for relocation.”

The situation in India varies from that in China because the government is attempting to improve their programs regarding conservation. Arpan Sharma mentions that there “seems to have been a significant improvement over previously recorded instances of such exercises.” India has been attempting to develop its political institutions for the past 50 years. Political development and strengthening of institutions are correlated with the incrementally improving accountability on behalf of the government.

International Response: Failings and Obligations

Finally, it is the international community’s responsibility to establish mechanisms to handle refugees and pressure countries to mitigate this problem. The term environmental refugee first appeared in the 1970’s, and so this is a relatively recent phenomenon the international community has had trouble grappling with. The current definition of refugee excludes those who have been hurt by the environment.The UNHCR traditional definition of a refugee is “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a certain group, or political opinion.” Thus, it is difficult for individuals displaced due to industrialization and deteriorating environmental conditions to get help. As stated by Amber Jamil in the American Interest, “climate-induced, cross-border migrations trigger few if any protections or assistance mechanisms.” Put simply, international law has failed in protecting environmental refugees. This is best seen in the case of Ioane Teitiota. Teitiota was born in one of the islands in the Republic of Kiribati. His island was sinking and becoming almost uninhabitable. The ocean had knocked down the seawall and had flooded the family compound twice. Yet, he lost his appeal for asylum in New Zealand because, by definition, he was not a refugee. While his case wasn’t directly caused by development, it still demonstrates how ill-equipped the system is to handle those forcibly moved by their environment. The lack of action from the international community exacerbates the issue of development-induced migration because it legitimizes, or at the very least accepts, such actions by the government.

Industrialization and structural development will continue as countries are further integrated into the global economy. To meet the demands of citizens, the economy, and maybe even to correct past wrongs, such development is inevitable. This is why it is imperative that the international community works with governments in establishing proper methods of accountability and recourse.

Featured Image Source: http://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1016301/environmental-refugees-rise