In 2017, the brinkmanship between Kim Jong-Un and President Trump and the looming prospect of conflict drew a great deal of attention to the Korean Peninsula. Meanwhile, a less dramatic but nonetheless defining geopolitical struggle has been unfolding further south in the East Asia region, in the South China Sea. At the heart of these tensions is the hard-edged power politics being practiced by China in pursuit of its national interest.

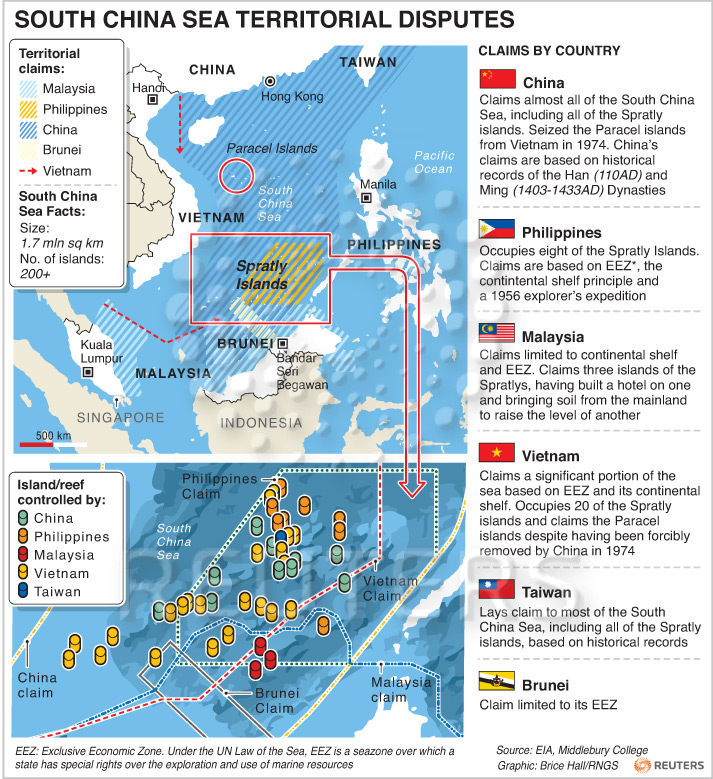

In addition to fishing grounds, the South China Sea contains an abundance of energy resources, with oil reserves of at least 7 billion barrels and natural gas reserves of 900 trillion cubic feet. This area also includes a narrow strip of water between the Malay Peninsula and the island of Sumatra, the Malacca Strait, which connects the Indian and Pacific Ocean. As the primary route to and from an economically booming Asia, it has become one of the world’s premier shipping lanes, with an estimated one-third of global shipping passes through the Malacca Strait. These factors combined give a strategic importance to the South China Sea that has led to numerous states — Brunei, the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam — each pressing their own claims to the region.

While such disputes have long existed, the increasingly strident attitude taken by China to its territorial claims has brought about an escalation of these tensions. Other states in the region generally base such claims on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) — an important legal charter mandating freedom of navigation and granting ‘economic exclusion zones’ to states within areas a certain distance from their shores — that the US has upheld since the Second World War. China, however, lays claim to an area far greater than the waters and islands close to its shores, leading an international tribune to find no legal basis for China’s claims. What China calls the ‘Nine-Dash Line’ forms the basis of its claims; the area within this “line” includes most of the South China Sea, bringing China into conflict with neighboring countries like Vietnam and the Philippines. The ‘Nine-Dash Line’ is also vague and imprecise, leading some to view its claims as strategic ambiguity, which Marina Tsirbas of the Australian National University argues is useful for buying time if you have not quite figured out what you want to do and how you want to lay claim to certain features (and enforce that claim).”

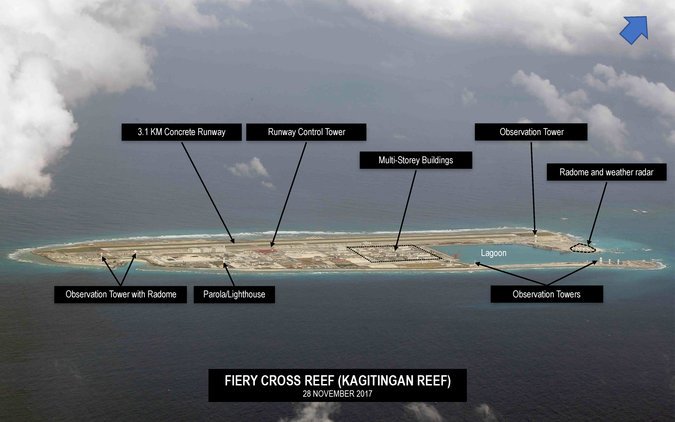

Despite a ruling by an international tribunal in The Hague in favor of the Philippines in its dispute with China, the latter issued a defiant statement saying that it had little intention of backing down. Recent photos obtained by a newspaper in the Philippines indicate that reality matches this rhetoric. The photos of the disputed region show military outposts built on artificial islands, complete with hangars, helipads, and bunkers, some of which are allegedly four times the size of Buckingham Palace. The speed with which China has proceeded with what is in effect a de-facto annexation of this area indicates that it no longer feels the need to comply with liberal, rules-based international norms when it comes to its territorial disputes.

This boldness — or belligerence, depending on one’s perspective — in China’s foreign policy partly reflects nervousness on China’s part about its particular strategic vulnerability when it comes to maritime trade. Maritime trade, including the energy supplies that the Chinese economy depends heavily upon, must pass through shipping lanes close to the shores of other states when going to and from China’s ports. Thus China is highly vulnerable to naval blockade in the event of a conflict, as its then-President Hu Jintao warned in 2003 when he explicitly referred to the “Malacca Dilemma.” The Chinese Communist Party relies on strong economic growth to maintain its popular legitimacy, so such a blockade would be incredibly dangerous for the regime. For this reason, the Chinese government sees gaining greater control over the Malacca Strait as a vital interest.

That China has claimed that the ‘Nine-Dash Line’ is based on the ‘historical rights’ of China as a ‘great nation’ is also telling. While China has long had to contend with the “Malacca Dilemma”, it now feels able to assertively press these claims as a result of its rise as the world’s second-largest economy, and its consequent ability to modernize militarily. China’s economic rise has come hand in hand with a resurgence of nationalist sentiment in the country. This nationalism has been encouraged by the Communist Party, which has sought to bolster their legitimacy with public rhetoric and initiatives that emphasize China’s right to reassert itself after the “100 years of humiliation” brought about by colonialism. Public opinion and influential Chinese newspapers, with the latter, no doubt heavily influencing the former, are strongly in favor of a vigorous approach to China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea. The angry backlash in China’s state media against Britain’s decision to send a warship through contested waters is a case in point. Thus even in those instances where it may be wise take a step back, the Chinese government may feel compelled to act otherwise due to pressure from the nationalist public sentiment that they have helped to bring about.

Increasingly, China’s neighbors are not strongly disputing its assertive actions. This can be seen in how China-Philippines relations have improved since President Duterte took power. That China’s assertive geopolitical maneuvers are not eliciting an exclusively hostile response from other powers like the Philippines is emblematic of the way that the balance of power in the region has shifted, as a result of the decline of US power and the rise of China as a major military and economic power. Historically, the US has played a hegemonic role in the region, upholding freedom of the seas and international law. This policing role played by the US over the past few decades has enabled regional cooperation, such as the creation of ASEAN, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. However, many of China’s neighbors correctly perceive that America’s enormous budget deficits and involvement in military quagmires in the Middle East will reduce its ability to actively involve itself in East Asia going into the future.

This long-term trend of declining US power in the region has been compounded by Trump’s undiplomatic exhortations for America to make its allies pay to defend themselves, as well as his generally erratic behavior. Trump’s weaker commitment to security alliances makes it rational for Southeast Asian states to calculate that the US may not come to their rescue in the event of a conflict with China, and rational for China to continue to consolidate its military control of the South China Sea without fear of the US. Thus US withdrawal from its policing role in East Asia is enabling China to fill the vacuum with its own brand of realpolitik, a way of doing politics based around the national interest and competition among nations for power rather than legalistic principles or liberal ideals.

Countries like the Philippines are therefore increasingly forced to accommodate themselves to Chinese power by playing a more subservient role. A similar dynamic can be observed with Singapore. Traditionally one of the strongest Western allies in the region, it recently agreed to carry out joint military exercises with China. That Singapore should feel the need to do so indicates a similar desire to hedge its bets; if the foreign policy strategy of the US can no longer be predicted with the same certainty, then it is better to not alienate China, or so the thinking goes. Moreover, playing such a role also brings benefits beyond avoiding a war that cannot be won. As a result of Duterte putting the Philippines’ territorial claims on the backburner, China has increased its aid to the country. This contrasts with its previous approach in stopping purchases of bananas from the Philippines, when the latter was still strongly contesting China’s claim to the Scarborough Shoal.

China has thus gradually increased its control over large areas of the South China Sea through a ‘carrot and stick’ strategy. China uses military and economic coercion, the stick, alongside inducements to rival states to gain greater economic ties, the carrot, in order to advance its claims. This fits into what Henry Kissinger identifies in On China as China’s ancient strategic tradition of incrementally pursuing strategic encirclement of an opponent; he argues that “Rarely did Chinese statesmen risk the outcome of a conflict on a single all-or-nothing clash; elaborate multiyear maneuvers were closer to their style… the Chinese ideal stressed subtlety, indirection and the patient accumulation of relative advantage.” China avoids the kind of overt, brute force used by Russia in its expansionist efforts, preferring a more refined — but nonetheless coercive — approach to increasing its military reach.

Seen more broadly, China’s increasingly successful efforts to carve out a sphere of influence in the South China Sea exemplify the disintegration of the rules-based, liberal international order that the US has largely, albeit not flawlessly, upheld since the end of World War 2. In its place, a multipolar order is emerging where states like China can pursue power in a hard-edged way with little fear of negative repercussions. The famous observation of the ancient Greek historian Thucydides that “the strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must” seems ever more fitting in the case of the South China Sea.

Featured Image Source: http://www.chiangraitimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/kennan2.jpg

Be First to Comment