Gun reform—suddenly the contention is palpable and explosive. The current hyperfocus is wholly attributable to the courageous and unyielding student survivors turned activists who survived the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School mass shooting. For those of us with a modicum of melanin in our skin, however, gun violence and the resultant fight to mitigate it has been front and center long before that dreadful February day in Parkland.

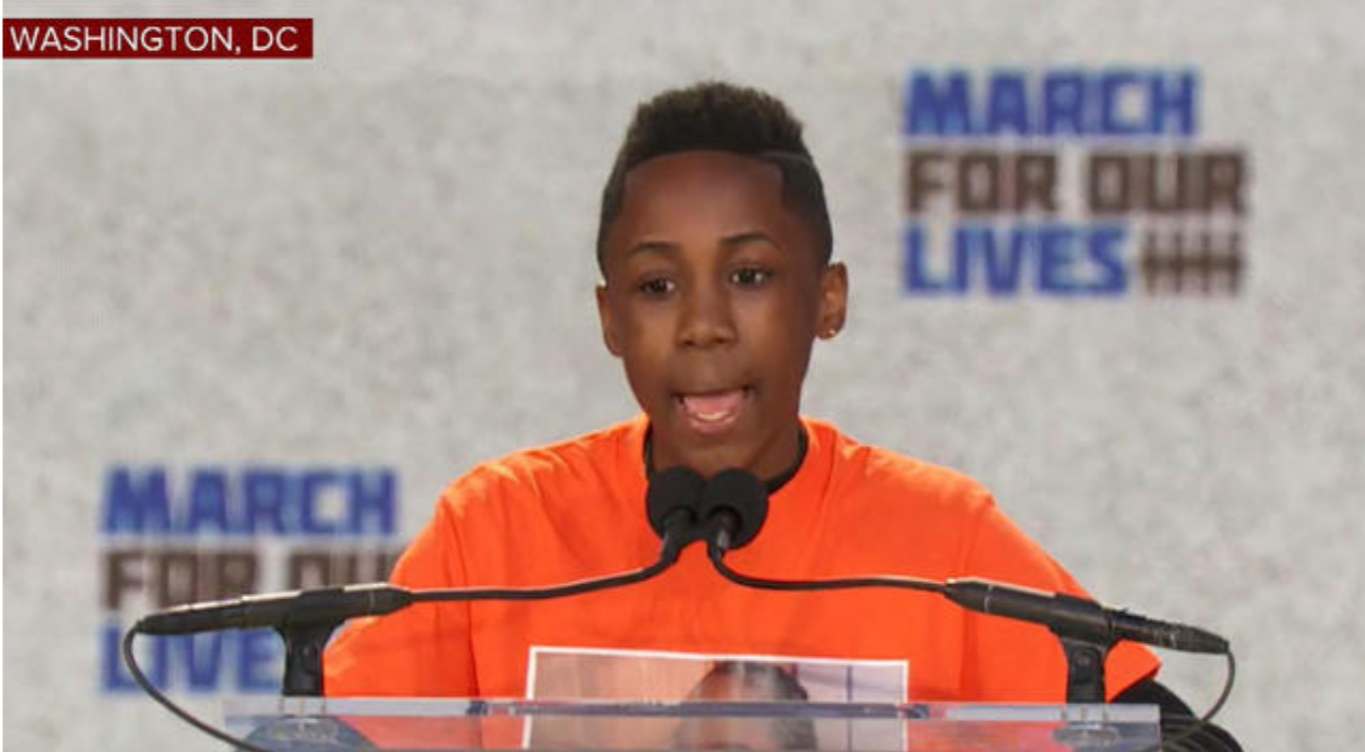

Edna Chavez, a 17-year old from South Los Angeles, told the crowd at the March for Our Lives protest last month, “I have learned to duck from bullets before I learned how to read.” Another speaker, Christopher Underwood, lamenting the death of his brother who died on his 15th birthday, professed: “Senseless gun violence took away my childhood.”

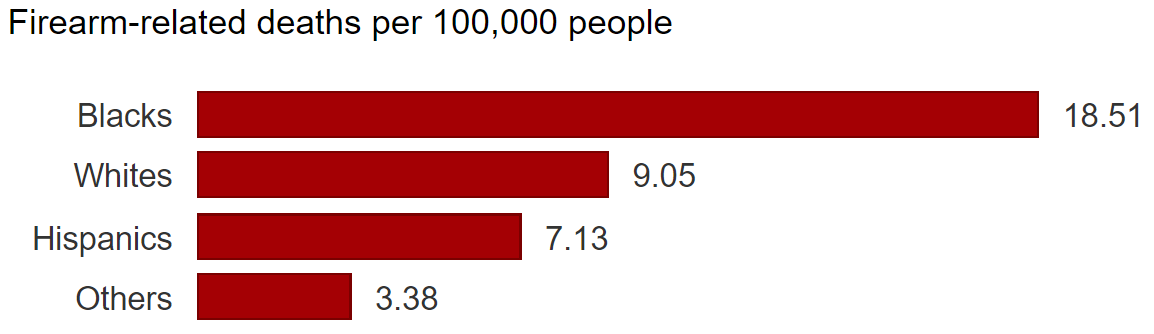

The speakers’ cases, while viscerally revolting, are run-of-the-mill in the USA. Black Americans make up just 6 percent of the population but 18 percent of all gun deaths. While all children are particularly vulnerable to gun violence, black children are ten times more likely to be killed than white and Asian-American children. While blacks are also the predominant victims in mass shootings, a bulk of the deaths are from the 99 percent of gun deaths that are not mass shootings. Another risk factor is law enforcement, as the police kill more unarmed black people than any other group.

There are, however, some like Nick Selby at the National Review who think blacks are more affected by gun violence because they have some proclivity for crime. He claims that race is not the cause for arrest-related deaths, but rather that ”an officer is not as likely to shoot the cashier selling him a cup of coffee as he is to shoot a citizen with an outstanding warrant he has just pulled over.” However, this ignores the dominant stereotype instilling black people with criminality. The statistics on marijuana convictions are one quick way to see how this materializes: despite equal usage rates, blacks are nearly four times more likely to be arrested than whites.

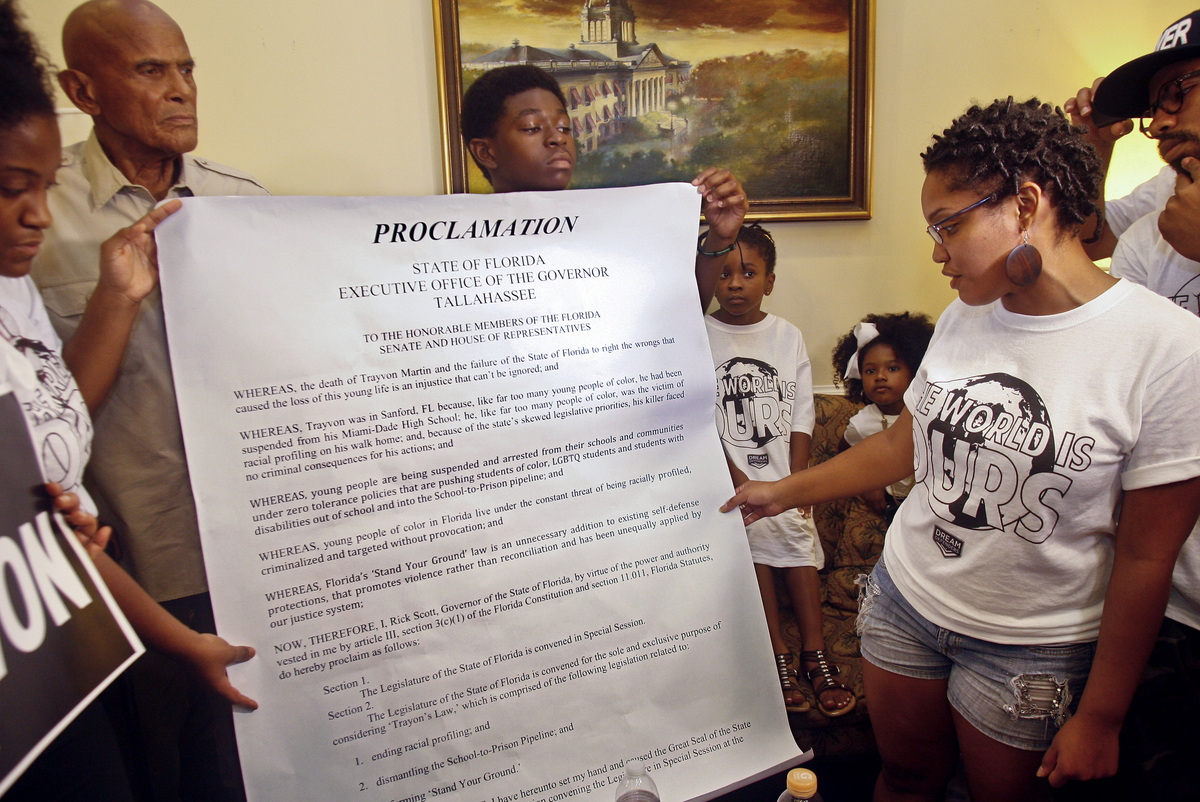

The Journal of Pediatrics, in a preeminent study on gun violence inflicted on American children, reported that 19 children are killed or injured by gun violence per day; there’s no logical explanation for this. Children are never permissible targets or culpable for execution, guns should not be their second leading cause of death. This is why black activists of all ages have been organizing on behalf of the preservation of black lives, struggling to end this cycle of violence. In 2013, the friends of Hadiya Pendleton, a high school honors student shot in the back in a Chicago park, started a movement against senseless gun violence. While “Project Orange Tree” saw support from the likes of Russell Simmons and even members of Congress, it did not enter the national spotlight in the same way that the Parkland survivors’ #NeverAgain campaign has. The Dream Defenders rallied for a repeal of the Florida “stand your ground” law largely responsible for absolving the recurring offender who murdered Trayvon Martin; they even worked with the NAACP and Florida Legal Services to bring their grievances to the United Nations. This group, led by young blacks and people of color, jolted into existence after Trayvon’s murder. Although Governor Rick Scott rebuffed their demands and recently expanded the stand your ground law, they continue to work in a plethora of areas that affect communities of color.

Besides just being ignored, black activists face demonization in the media, as seen in the response to peaceful protesters in the NFL, and place a target on themselves when they step into the public eye as many are hostile to their goals. When students at Eaton High in Fort Worth held a peaceful demonstration to honor the Parkland victims and discuss gun violence, the scene deteriorated into infighting precipitated by mostly white antagonists who brought confederate flags and shouted racial slurs at students of color.

The young Parkland survivor-protesters stepped up to bridge the gap by inviting fellow high school leaders against gun violence from Chicago to fly out to a meeting in Parkland — both one of the safest cities in America and the site of one of its deadliest mass school shootings. Used to being ostracized, the Chicago students were wary at first, but when the Parkland students expressed apology for the privilege they enjoyed one of the guests broke out in tears saying: “any barriers that could have divided us completely disintegrated in that moment.”

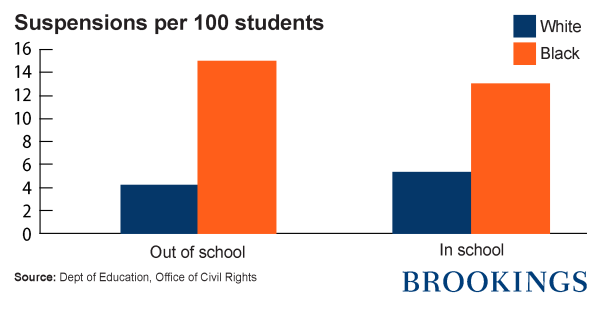

Gov. Rick Scott pushed out a plan to address gun violence in Florida which, astoundingly, became a $400 million dollar bipartisan bill that actuated a ban on the sale of accessories that turn rifles into fully automatic assault weapons, in addition to some other new gun restrictions. It is the fact that white voices took hold of their platform and utilized their social capital to solicit change that brought about this institutional response. The bill however, in its failure to listen to minority communities, will likely augment harm to students of color by amplifying the presence of guns on school campuses by allocating a $67 million dollar fund to train and arm school staff. This is one of the reasons that Kamia Brown, a State House Democrat, voted against the bill, telling NPR that it “was an inefficient attempt to do a quick fix to a large problem that we have.”

Time and again we see that school penal authorities and police target and discriminate against vulnerable students—the ACLU has won lawsuits on behalf of disabled, as well as black and brown, students who endured overtly aggressive treatment by school authorities. Video footage of an incident in Memphis on April 12th shows a teacher grabbing and dragging a 7-year old black child by his feet off of a school bus as he hangs upside down. Giving teachers weapons, then, is a frightening idea for parents of minority students. Nonetheless, the president continues to endorse the NRA and advocate that teachers should carry guns in the classroom.

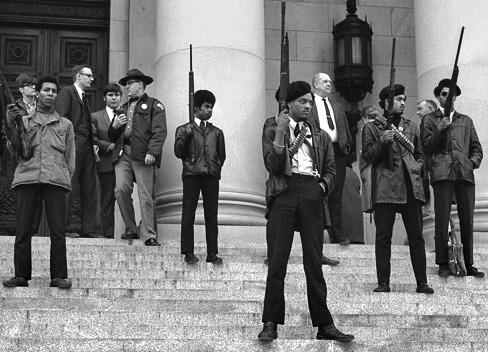

The racial chasm surrounding guns in America has discernible origins in governmental regulation of firearms. After emancipation, several southern states barred blacks from owning guns. When members of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense wanted to arm themselves, the newly created National Rifle Association and the federal government issued public polemics and prompted the 1968 passage of one of the most thorough federal gun laws. Shortly thereafter, the NRA transforms from an innocuous organization of hunters into, in the words of a former employee, a “cynical, mercenary political cult.” The propaganda machine they maintain to make guns a strong political and ideological symbol among white America banks on entrenched fears of black gun ownership. The history of obstructing blacks from owning guns and mongering racial anxiety is exhibited through the Ku Klux Klan, America’s “first gun control group.” The NRA is now attempting to speak to minority communities by utilizing a black person in their media campaigns, all the while knowing that images of black men with guns drive white men to buy guns. They know their audience. Studies show the profile of gun owners is specific and consistent: white, financially distressed, non-religious, uneducated, and beset by racial fears.

The racial dichotomy perpetuated and championed by the NRA in conjunction with the government obfuscates gun violence in communities of color from public concern and pardons white aggressors. The shrewd move to pander to racial minorities is remarkably egregious coming from the organization responsible for inhibiting the knowledge and understanding of gun violence so essential to redressing the plight of their communities. In 1993, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a study linking guns in the household with a higher probability of homicide in that home. The NRA, knowing information like this could affect public policies to its detriment, acted swiftly and in 1996 successfully incorporated a statutory ban on government funded gun violence research—known as the Dickey Amendment. In the wake of the Parkland shooting, the federal government issued a minor directive toward allowing the CDC more flexibility, but gun policy expert Daniel Webster told CNN: “Talk is cheap. What is their actions? Did they put money in the CDC budget for firearms research? Did they put money into (the National Institutes of Health) budget for research? Did they abolish the Dickey Amendment? No. No. No. No. No.”

The bedrock of racial inquietude that guns stand on has created a divisive and dangerous atmosphere where racial animus manifests into gun violence, gun sales proliferate based on a fear of the other, and whiteness averts culpability. Whites are less in favor of gun control and less fearful of gun violence, and know that they can assemble into armed militias to audaciously threaten the government and get off scot-free. White gun owners are likely to associate gun ownership with patriotism and civic heroism, but researchers have proven they are also more prone to racist views. The surge in hate crimes simmers under the radar as the media sanitizes and under-reports white murderers. While the FBI recently attempted to prosecute an activist who was part of a black armed self-defense groups as a “black identity extremist”—a new, untenable domestic terrorism classification—alt-right extremism continues to go unperturbed. In the same vein, brown and black people get demonized for existing but no one points out that white, middle-class males are carrying out mass shootings in record numbers. The heightened tensions are driving up gun sales among blacks, along with other marginalized groups like the LGBTQ+ community.

What the Parkland student activists are attempting is something unprecedented: an intersectional, pro-gun control unified force capable of challenging the powerful faction of those who brandish pro-gun ideologies. Because the key leaders, sans Emma Gonzalez who is Latinx, are all non-black and predominantly white, this will require them to include black students at the forefront. After the Chicago meeting cited earlier, Black Parkland students called a pressed conference to express their exclusion from the movement. One of these students, Mei-Ling Ho-Shing, told The Huffington Post: “David Hogg, we’re proud of him, but he mentioned he was going to use his white privilege to be the voice for black communities, and we’re kind of sitting there like, ‘You know there are Stoneman Douglas students who could be that voice.’”

Certainly, there are differing consciousnesses around guns in colored versus white communities, where ignorance and stereotypes can beget further discord as well as inaction towards mitigating urban gun violence. With the recent Florida legislation we can see how leaving out blacks from the gun reform conversation can exacerbate current problems and fail to help the group most affected by gun violence. Black activists’ efforts towards justice are consistently deemed illicit, but their distinctive cultural experience makes them more familiar with the anti-gun violence cause and steps should be taken to integrate them into leadership roles. We cannot erase history, but we can move forward with historical and cultural competence to tackle the racially fraught issue of gun violence in a way that uplifts all members of the republic.

Featured Image Source: Black Panthers armed protest at the Washington state Capitol in 1969. LA Times, photo by University of California Press.

Be First to Comment