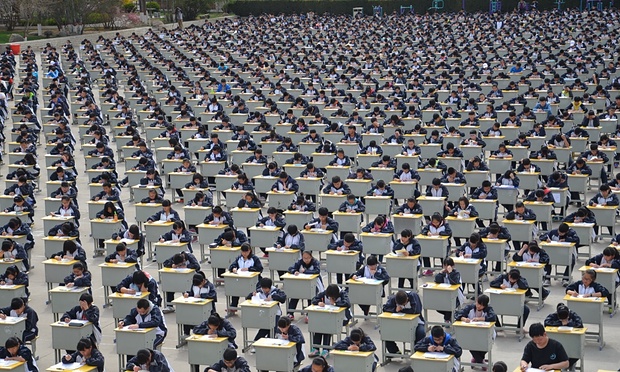

Every year, for two days in June, China comes to a standstill. Construction work is halted, traffic is diverted, and motorists are banned from honking, lest they disturb the nine and a half million teenagers taking a college entrance exam they believe will dictate their careers, wealth, and perhaps even marriage prospects. Drones are dispatched to monitor the rampant and sophisticated cheating, and anxious parents wait outside near the ambulances on hand to treat students — or parents — who collapse out of nerves.

Source: Time

Inside, students rush to answer prompts like, “The containers for milk are always square boxes; containers for mineral water are always round bottles; round wine bottles are usually placed in square boxes. Write a composition on the subtle philosophy of the round and square.”

The National Higher Education Entrance Examination, best known as the gaokao, is the sole determinant for admission to nearly all Chinese universities. In a society that can favor credentials over ability, a few points are considered the difference between a good or bad school, and a life of wealth or poverty. Futures are decided by students’ performance at a cramped desk and a three-digit score.

The not-so-secret truth is that even China’s top universities are comparatively easy —getting into them is the hard part. Schools may select just one in 500,000 applicants, and about 20 percent of students will not be accepted to any university at all. Only 1 percent make it into top universities every year. The final year of high school is devoted entirely to preparing for the gaokao’s difficult and esoteric questions on geography, math, Chinese, philosophy, and more. Most start preparing years in advance.

“Our final purpose, our whole life before 18, is for the gaokao. Every teacher says, ‘If you don’t pass the gaokao, and you don’t go to college, your life is ruined,’” said Amy Fu, a student at Beijing International Studies University taking classes at the University of California, Berkeley for the summer.

China recognizes the exam is imperfect; the test is widely criticized for putting overwhelming pressure on children and discouraging critical thinking. Varying regional testing standards give preference to the rich and have left those cheated by the “unfair” quota distribution furious. But ultimately, most put up with it. In a country so large and filled with corruption, a uniform anonymously-graded test is the great equalizer that rewards hard work. It gives the disadvantaged a chance at a successful life. Chinese call it a dumuqiao, or impartial “single log bridge” that all must cross. It’s meritocratic because it’s rough for everyone.

“I still think it’s the fairest examination in China. The score is there, you can’t fake it,” Fu said.

China’s tradition of the high-stakes exam originated in the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. to 220 C.E.). The imperial examinations, or keju, were a mandatory test for aspiring Chinese bureaucrats. The exams ensured that government officials were chosen for merit, rather than their money or lineage. In theory, any adult male could become a high-ranking government official by passing the exam. The reality, of course, is that only the elite could afford the lifestyle of studying and expensive tutors necessary to pass the rigorous exam, but notable low-born exceptions do exist. Regional quotas meant elites in disadvantaged peripheral provinces had the same opportunities as those in wealthy regions.

Candidates for the three-day test were locked in a cell, where they took their meals, slept and answered questions on geography, Confucian classics, their ability to write, civil law and more. Applicants were checked for hidden scrolls and writing notes in underwear was a favored form of cheating — until the government caught on. Nervous collapses were common. Only 5 percent of applicants passed.

Though not a direct descendant, many consider the gaokao a “distant relative” of the imperial examinations — flaws and all.

“The inequality in the Chinese college entrance examination is mainly the inequality between the social classes,” said Dong Meiying, associate professor of educational science at Nanjing Xiaozhuang University. “In colleges and universities, the college entrance exam has played a role in solidifying the social class.”

China’s wealthy often purchase intensive study programs and hire private tutors for their children. Of course, the same happens in America — SAT tutors certainly give rich kids an advantage the less privileged lack. But the SAT tests academic fundamentals and critical thinking; it’s conceivable that high-school graduates have a decent shot, regardless of preparation. The gaokao instead asks questions that favor those who commit massive amounts of time to rigorous drilling and rote memorization. “Arms races” develop between wealthy neighbors to ensure their child is the best prepared.

Though citizens get admissions preference into their local university, many of the top schools are located in Beijing and Shanghai. Students in these cities are beneficiaries of significant quotas for these elite universities, even though their gaokao scores are already high. China’s housing registration structure, the hukou system, makes internal migration near impossible, meaning rural poor can’t move to regions with better schools.

Questions on the exam also differ by region. Fu would skip the notoriously difficult practice tests from Shandong and Jiangsu provinces, knowing their Beijing exam would never be so hard. Regions with a poorer education system may be stuck with a harder exam, meaning only the extremely gifted few can escape their disadvantaged social class.

Parents frequently point out the intense pressure a monolithic, one-shot exam has on children. Nervous faints are common on exam day, and suicides are a regular hallmark of every exam season. A 2014 study claimed that gaokao stress was a contributing factor in 93 percent of high school suicide cases. A middle school in Hebei province added grates to its upper-floor dormitory balcony after two students leaped to their deaths in the months leading up to the gaokao.

The government recognizes a need for reform, but talk of change is frequently met with enraged backlash from parents and students. No parent wants their kid to be the “guinea pig” for a new exam format, given the significance exam scores can have on children’s future.

China’s Ministry of Education is in the process of building a new, more comprehensive exam that allows students to take sections of the exam multiple times over the course of their high school career. The change is designed to ease the tension inherent to a one-shot exam. Some argue that it fails to address the root of the problem — the exam-based education system of China remains, and futures are still based on test scores.

Elite Chinese universities are also experimenting with holistic admissions methods in an effort to accept well-rounded students over those just gifted in test-taking. Face-to-face interviews, letters of recommendation and other methods would assess students’ “soft skills.” Gaokao scores would no longer be the sole gatekeeper for higher education.

Many in China, however, are skeptical of a comprehensive admissions process. For all its flaws, gaokao scores are simple, objective, and anonymously graded, giving Chinese faith in its integrity. The same cannot be said for interviews and other holistic application procedures. Given China’s notorious corruption, many parents are understandably concerned that elites would use money and connections to ensure their child admission into a top university.

“It’s just another loophole,” Fu said.

Alex Guo, another student at Beijing International Studies University, said she knows a student who bought a space at Tsinghua University — China’s MIT. She claimed this is only a privilege of the extremely wealthy and connected.

Tackling education inequality has become a larger challenge. University admissions in China are a zero-sum game — allocating more space for the poor and marginalized means taking away space from another group. When the stakes are your child’s future, you can expect parents to get upset when that space is threatened.

Parents in Jiangsu province took to the streets in 2016 to protest Beijing’s announcement that their wealthy province would be allocating 38,000 spots in its top-tier universities to children from ten of China’s poorer inland regions. These spaces were previously given to Jiangsu residents themselves.

Source: Sixth Tone

They surrounded the provincial Ministry of Education to shout and wave signs reading “Fairness in education! Oppose the gaokao admissions reduction!” Local police were filmed arresting, beating and carrying off protestors. There was a report of self-immolation.

Jiangsu already feels at a disadvantage. In Beijing, the acceptance rate to first-tier universities is 24 percent. It’s only nine percent in Jiangsu, despite the fact that their average gaokao score is higher. The change felt unfair, especially considering Beijing and Shanghai were not given a similar large-scale quota reduction.

China’s provincial urban middle-class has been the bedrock of the Communist Party’s support, but conflicts over the gaokao are forming a more conscious and active middle-class. They feel trapped inside their education system — caught between the poorer regions they consider unfairly compensated and the rich districts that benefit from better resources and local admissions benefits. Social media chat rooms and organized protests give confidence to the middle-class.

In an effort to avoid the inherent inequalities of the gaokao, some families are opting out of the system entirely. International education was once a privilege of the ultra-wealthy but has become more common among the upper-middle and even middle-classes over the last decade. For some, avoiding the gaokao is reason enough to study abroad.

Studying abroad remains a privilege, however. Opting out of the gaokao makes you ineligible for Chinese universities, and “international track” programs that prepare students for standardized testing abroad are taken by just 3 percent of the population. Students planning on taking the gaokao are already intent on attending a national university and are less likely to consider international alternatives.

The University of New Hampshire is one of few American institutions to accept gaokao scores as a component of their admissions process. Students who scored too low for their desired university and never considered studying abroad no longer have to spend another year studying to retake the exam.

The University of New Hampshire received only a handful of applications for this fall’s semester, but expect to see more applications next year when they can better promote the program to Chinese students, said university spokesperson Erika Mantz.

There is still reluctance among many foreign institutions to accept gaokao scores, however. Foreign critics of the exam often critique the test’s emphasis on rote memorization and its serious disregard for critical thinking. Fu joked that her classmates may have received better exam scores than she, but they can hardly hold a conversation.

A study by Stanford University found that Chinese students excel at critical thinking skills — until they start college. Chinese freshmen in computer science and engineering programs were considered two or three years ahead of their American and Russian peers in critical thinking skills but showed virtually no improvement after two years. Non-Chinese classmates continued to develop these skills.

“By the time Chinese students reach university, they’re drained,” said Scott Rozelle, an expert in Chinese education and co-author of the study. “The gaokao is harder than anything they’ll do in college.”

Official statistics show that nearly all students graduate university within four years, and students know they will graduate even if they don’t study. The Stanford study’s findings are preliminary, but to Chinese students, the findings are obvious.

“I think that’s the sick part of the education system, you know. In China, it’s hard to get [into university] and easy to get out,” said Guo. “You can just play on computers all day and graduate.”

How China manages its education system matters. Changes to the gaokao have solidified the middle-class and pushed students to study abroad. American universities are making room for Chinese gaokao-takers who never considered attending a foreign university. Most importantly, a workforce that lacks developed critical thinking skills will do little to revitalize China’s slowing economy.

Featured Image Credit: Daily Mail

Be First to Comment