UN Special Rapporteur Yanghee Lee, upon reporting about the Rohingya crisis last March, concluded, “Facebook has now turned into a beast.”

Indeed it has. In Myanmar, what was once intended as a harmless social networking platform has warped into a powerful vessel for the government to target its citizens with inflammatory rhetoric and propaganda. In the past five years, Facebook has evolved into a sinister arena in which hate speech circulates unchecked amongst its technologically-uninformed Burmese users, rousing people to violence against the Rohingya.

Social media platform fuels Rohingya crisis

The Rohingya are a Muslim minority within Myanmar that have been subject to persecution from the Burmese government for decades. The passage of a citizenship law in 1982 left this ethnic minority group stateless after years of acrimonious ethnic and religious tensions between them and the Buddhist majority Burmese. Stripped of their citizenship, the Rohingya have had no state to call upon for their protection of safety, or the upholding of their basic human rights. Even though the Rohingya have resided in Burma for centuries, they are accused of being illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and terrorists against their own homeland.

Citing the ARSA attacks as proof that the Rohingya constitute a threat to national security, the Burmese military launched a massive and brutal genocidal campaign in response. In just the past year, they have been responsible for a staggering number of extrajudicial killings, widespread rape, torture – but also of burning entire Rohingya villages to the ground. As of now, close to ninety percent of the entire Rohingya population have fled to Bangladesh’s refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, making it the world’s fastest-growing refugee crisis.

The dangerous narrative that the Rohingya must be exterminated is catching fire with marked speed and virulence, especially online. In fact, the Guardian published a graph that exhibits an extremely salient spike in vitriolic rhetoric on Facebook following the ARSA attacks that have fueled hatred against the Rohingya and led to increased violence against the minority. This brings us to an important point —never has a humanitarian crisis been so obviously and devastatingly impacted by what’s occurring in the realm of cyberspace.

Facebook as the only source of information

Just a decade ago, the mobile phone penetration in Myanmar was less than 5 percent. Cell phones were a luxury item available to few, with the price of some SIM cards upwards of a thousand dollars. But with the recent opening up of Myanmar’s airwaves to foreign investors, the sudden explosion of supply in SIM cards caused their prices to drop to nearly $1.50. In a single year, the number of internet users in the country skyrocketed to 97 percent.

The surge of mobile phone users correlates to Facebook’s rise as the social media platform of choice in the country. Not only is it one of the only portals that support Burmese text, but it also comes with the convenience of being pre-installed in every single smartphone. The app’s accessibility and universality of use led Facebook to essentially function as the de-facto Internet in Myanmar — and, by extension, the main source of news to the Burmese.

But the recent introduction of the app to Myanmar and low digital literacy of its users is a dangerous combination. Without adequate education to discern the accuracy of information online, Burmese citizens often uncritically accept the nationalistic propaganda and false information that inundates the site.

Anti-Rohingya cartoons, overtly pro-government propaganda, doctored photos, unverified accounts of violence by the Rohingya, and rants for their extermination can go viral in mere seconds. The invective of these posts dehumanizes this population further, which emboldens the Burmese to act upon calls of violence. For example, following an unsubstantiated rumor posted on Facebook that a Muslim man raped a Buddhist employee, a massive riot in Mandalay led to two deaths and fourteen injuries in 2014. In other words, the misinformation proliferated online this site is responsible for rising death tolls offline and has contributed to a climate of fear that translates to real acts of violence on the ground, even by everyday citizens.

Genocide or self-defense? Depends who you ask

This digital illiteracy has been exploited by powerful figures to push forward a dangerous narrative that the Rohingya threaten the security of the nation and must be dealt with accordingly. The state-backed media, The Global New Light of Myanmar, has popular posts from November 2016 that allude to the Rohingya as terrorists and “detestable human fleas” that subvert national unity. The op-ed states, “Those human fleas are destroying our world by killing people and harming others’ sovereignty. Likewise, our country is also facing the danger of the human fleas…We should not underestimate this enemy.” The fact that such inflammatory sentiments are officially upheld by legitimate governmental figures online justifies, in the eyes of many Burmese citizens, the genocide as a form of self-defense.

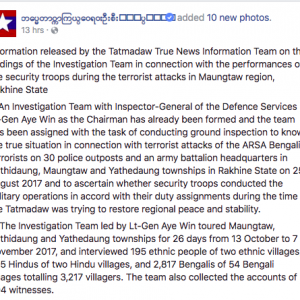

The Burmese military also uses Facebook as a megaphone to advance the ‘self-defense’ narrative and simultaneously excuse its complicity in mass slaughter, rape, torture, and egregious human rights abuses.

The military employs fear-mongering to justify violence against the ‘enemy’ by equating the Rohingya with outsiders that pose a threat to Burma’s security and stability. For example, in one official Facebook post in 2017, the Burmese military refer to the Rohingya to ‘Bengali terrorists’ over twenty times while advocating for its exoneration of any violence against the people. While ‘terrorist’ is highly charged for obvious reasons, the word ‘Bengali’ itself is also notably offensive, implying that the Rohingya are interlopers from Bangladesh and therefore do not belong in Myanmar. As of today, this post has been shared over 600 times.

Facebook, though warned multiple times of misuse of their platform in Myanmar, has been woefully inadequate in curbing hate speech on the site. A recent Reuters investigation this August showed evidence that Facebook has failed to take down over 1,000 derogatory posts, comments, and photos against the minority that flagrantly violate their Community Standards. Most of this stems from their faulty translating mechanism, a feature which Facebook has since removed, that cannot accurately detect hate speech in Burmese. In response to the report last month, Facebook admitted that they were “too slow to prevent misinformation and hate” in Myanmar and committed to improving their translating service and working with local groups on the ground in its operations.

Facebook’s Responsibility?

Considering what’s occurring in Myanmar, to what extent should Facebook be held accountable for the rising death tolls overseas, if at all? After all, companies often cite the fact that their role is different from that of the state, and thus don’t hold the same level of obligation to protect as governments do. However, it’s not a leap to say that tech giants rival even nation-states in the amount of information, resources, influence, and political power they possess. If that’s the case, should they not also share a similar burden of responsibility as governments in their role in world affairs – such as perpetuating genocide and crimes against humanity?

As long as Facebook evades culpability for what’s occurring in Myanmar, the implicit message is that tech companies are not responsible for the havoc ensued with the unmanaged use of their products. This situation sets an alarming precedent for how tech companies will see their responsibility, or lack thereof, in global crises to which they have directly contributed.

When Facebook was innocuously created within the confines of a small Harvard dorm room, no one anticipated that it would eventually harness such devastating influence – to the point of having blood on its hands. But, on the flip side, that same influence has equal potential to rebuild broken relationships, reconnect war-torn families, and recover its original intent of being a social network that makes “the world more open.” For that to happen, it must be regulated by accountability measures and guided by a clearly-set code of conduct – and only within these boundaries can we begin the restoring process, not only in Myanmar but in other impacted areas around the world.

Disclaimer: The author of this article is affiliated with the UC Berkeley Human Rights Center, which has previously contributed to reports of Facebook’s presence in Myanmar.

Be First to Comment