“If only those with opposing political views were able to engage in conversation, overall animosity would decrease.” While good-natured and opportunistic, evidence consistently proves this theory wrong. There is a growing body of research in America that seeks to understand political polarization. Unsurprisingly, digital forms of communication are unhelpful. Examples abound. My personal favorite is the chaos that ensued after an unknown social media staffer for Stephen Colbert tweeted an excerpt of a particularly risqué skit from “The Colbert Report” in 2014. Colbert, whose career is based on mocking conservatism, satirized the then-new Washington Redskins’ Original Americans Foundation (yes, that’s real) by equating it to the made-up “Ching-Chong Ding-Dong Foundation for Sensitivity to Orientals or Whatever.” Colbert was pointing out the blatant hypocrisy of Dan Snyder, the multi-billionaire who owns the Washington Redskins. In that moment, Colbert allied with Native American activists, who “have long condemned Snyder’s philanthropy as an attempt to buy support for the moniker, a dictionary-defined racial slur.”

It is important to discuss whether satire is an effective political strategy or if stunts like Colbert’s simply continue to normalize insensitive rhetoric. Asian-American activist, Suey Park, is a staunch advocate of the latter, which is why she advised her Twitter following to get #CancelColbert trending after viewing the poorly-crafted tweet. The digital discourse surrounding the topic was suddenly explosive. A multiplicity of actors engaged in the popular debate, including Colbert fans who were “outraged at the outrage” expressed by Park and her followers. Trolls quickly flooded the scene, and the spotlight shifted away from issues around Native cultural commodification.

Park told The New Yorker that it was not her intention to get Colbert’s show canceled –– in fact, she likes it. Park says the campaign’s goal was to “critique white liberals who use forms of racial humor to mock more blatant forms of racism.” Park’s point, however, was lost in the firestorm. This cataclysm emphasized the fact that #hashtag activism, when done without foresight, undermines anti-oppression efforts. The only helpful sectors of Twitter are the niche populations of socially aware cultural critics, like #BlackTwitter, but they are often ignored or harassed, usually by Twitter itself.

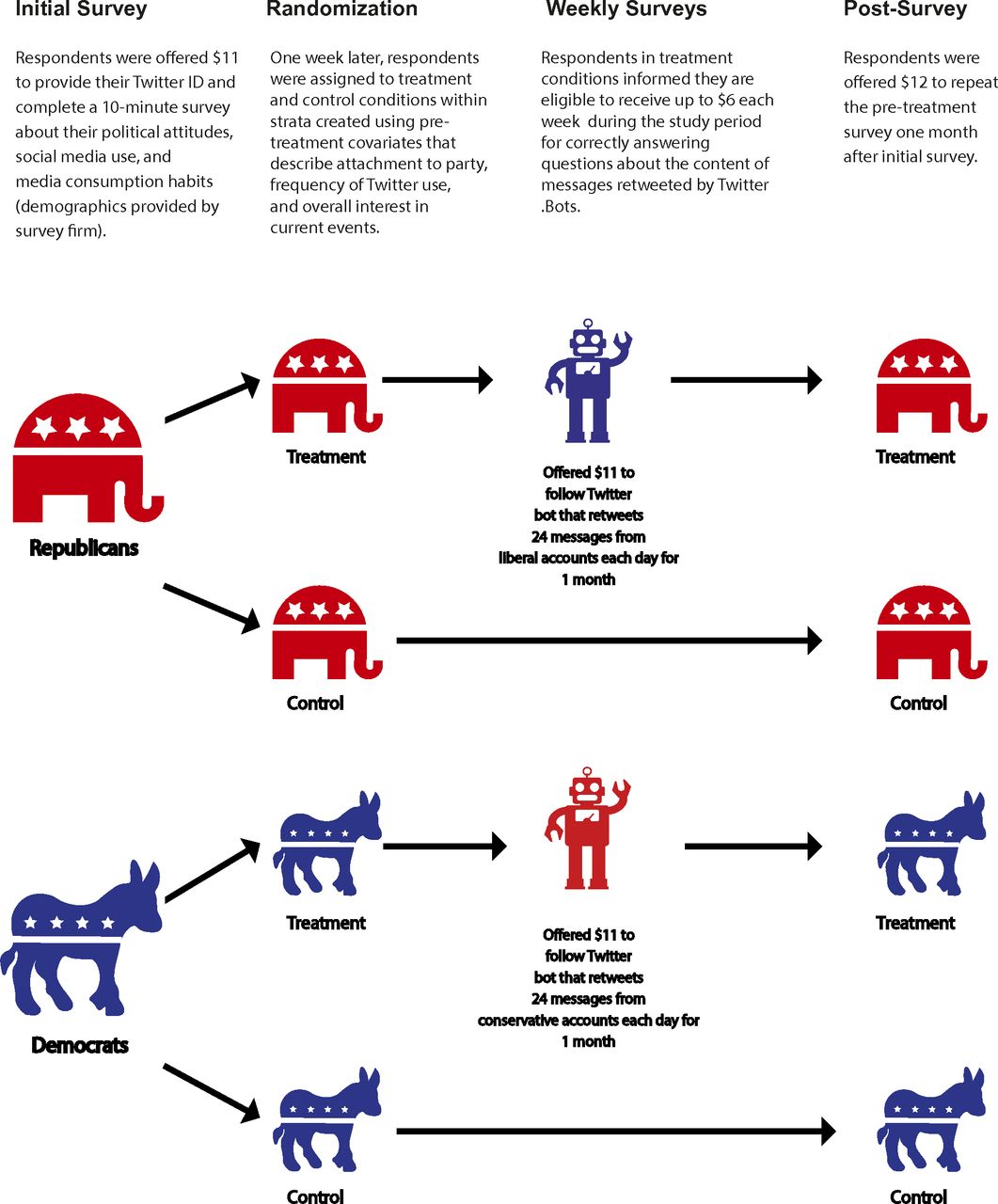

Elsewhere on the platform, partisan politics propagate tension. Sociologist Christopher Bail teamed up with a group of researchers to explore whether exposure to opposing political viewpoints on social media could reduce polarization. The researchers hired a professional survey firm to recruit more than 1,200 Republicans and Democrats to follow bots that retweeted messages from elite members of the user’s opposing party group.

The results support emergent literature that identifies a “backfire effect” which occurs when people come into contact with messages that conflict with their belief system. Bail found that Republican participants expressed viewpoints on social policies that were far more conservative than they were at the start of the study. The increase of liberal ideas among Democrats was not statistically significant.

Bail used this study to warn against a new practice being explored by Twitter’s chief executive, Jack Dorsey. The media firm is toying with the idea of using its algorithms to infer users’ political orientation and subsequently interject counter viewpoints into their timeline. This overly simplistic tactic would only fan partisan flames.

Dorsey vocalized the potential business adjustment during a testimony he gave to the House Energy and Commerce Committee. Congress requested the hearing to better understand Twitter’s elusive automated algorithms and content moderation processes. Conservatives and liberals are both concerned that they are being digitally silenced in this high-stakes political environment where our on and offline worlds have blurred together.

For many of us, social media’s role in society is shifting faster than we can follow. The launch of Facebook in 2004, along with the advent of smartphones, propelled social media into widespread renown. Social media networks are growing faster than ever, with Facebook standing at two billion users and Twitter at 328 million. Moreover, two-thirds of American adults say they get news from social media sites.

Nowadays, the general sentiment around the internet is vehemently negative. To say that hate and downright disrespect for other people has become grossly prevalent online is like saying that water is wet. A few years ago we celebrated social media for its capacity to bring people together and take down oppressive regimes worldwide. Both outtakes are flawed; social media is neither the panacea for world peace nor the downfall of humanity.

In 1964, prominent media scholar Michael McLuhan proposed that a techno-determinist worldview mistakenly disregards personal accountability by suggesting we are mere victims to the technology we build. Instead, technology is simply another tool we created. Like all tools, it is only an extension of ourselves, not some runaway autonomous monster.

In that case, it is fair to say that our social media landscape is representative of our social realities. The fiery resentment within America’s socio-political scene is palpable. The election of Donald Trump was undoubtedly a conservative backlash against the few policies President Obama was able to pass.

But this article isn’t another condemnation of Trump. While he capitalized on social media and civil unrest, it would be disingenuous to place the blame for America’s incivility entirely on him. Society was vulnerable at the start of Trump’s candidacy. Robert Putnam first sounded the alarm on America’s weakening social ties in his 2000 best-selling book “Bowling Alone.” Putnam presents data indicating that Americans are becoming increasingly disconnected from one another. He points to a decline in face-to-face social networks, such as neighborhood associations and bowling leagues, beginning in the 1960s.

Since the turn of the millennium, our offline relationships have been on a steady decline. Putnam reveals that every successive generation since the Baby Boomers has become less likely to volunteer in community organizations.

The internet has allowed for otherwise disparate individuals to connect, but it has also allowed people to favor digital interactions in place of face-to-face ones. While the Civil Rights Era deconstructed legal segregation, communities failed to interconnect in the following years. New identity-based support groups and social movements sprang up, but neighborhoods ceased to come together the way they did traditionally.

The timing begs the question: is diversity the culprit of socio-political discord? Ethnocentric conservatives and other white supremacists believe it is. Putnam’s latest work exposes the veracity in that belief—the most diverse communities experience the worst conditions of civic health. Putnam measures civic health by voting rates, levels of trust among neighbors, and involvement in communal projects.

The challenges of diversity are real: people are made uncomfortable by the different worldviews that emerge from heterogeneity. Even so, Putnam and others argue that if Americans can overcome the uneasiness caused by diversity, it can be extremely advantageous when it comes to creative innovation and productivity.

I agree with ethnocentric conservatives: increased diversity in all realms of society yielded the decline of unity in America. This is largely because far-right conservatism took hold as the dominant political ideology at the moment of racial integration. Upset with the rising popularity of counter-culture movements, moderate and liberal east coast Republicans were bulldozed by new southern Republicans.

Just when the most diverse range of individuals were able to freely contribute to politics, divisive ideologies pervaded the national psyche. Neo-conservatives submersed the country in exclusionary ideals rejecting racial equality, homosexuality, welfare, abortion, and sexual pleasure. The population has still yet to fully integrate and harbors conflicting ideas about American identity.

Bail’s research on political tribalism in the Twitter-sphere shows that attempts to tackle partisanship and reach unity must extend beyond Twitter. Twitter’s model is based on impulsiveness, desire for fame, and brevity. In order to make Twitter less hostile, some suggest modifications like higher character count limits. These alterations are useless if we do not alter the larger offline culture that normalizes vitriolic discourse.

Our technology currently exhibits the ugliest aspects of who we are. We have to do some honest introspection, to look in the mirror and critique our culture. Donald Trump isn’t an American anomaly. He’s as American as you or I. We have an unhealthy fixation on celebrity and a dangerous preoccupation with individualism. It is not doing ordinary folks any favors to promote value-less celebrity opulence.

George Packer argues that the allure of celebrities is greatest in times of entrenched inequality and distrust in institutions. He argues that the celebrity monuments we praise are “mindless diversions from a sluggish economy and chronic malaise.” We don’t get on Twitter to engage in insightful discussions, but to exalt celebrities and take a shot at becoming one ourselves.

We have a chance to make this contentious time the moment we chose to rebuke our worst tendencies and embrace collaborative community building. If we are willing to become more mindful media users and listen to alternative viewpoints, that is. Can we set down the tabloids and put making viral videos on the back-burner so that we can move this great nation out of the dark ages?

Feature Image Source: Mila Moldenhawer, UC Berkeley

2 Comments