“They take your young from you and you have so many taken, you are not whole,” says Helen Eason, an indigenous Australian woman. The Stolen Generations, only brought to a halt in the 1970s, remains a traumatic and salient black mark on Australia’s history. As part of the government’s Child Removal Policy, Helen Eason had her four children – including her 15-month-old son, taken from her for seven years by national authorities. Just as her children were effectively stolen from her, so too was their connection to their indigenous roots and their family. “Even when they come home, as much as they’re all there, all the pieces can never ever be put back together.”

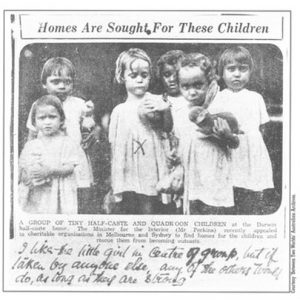

The longstanding practice of removing Aboriginal children from their homes was part of a wider national objective of assimilation. This practice confirmed colonial notions of white supremacy in Australia — forcing the rejection and denial of indigenous culture. Assimilation was founded on ideals of white supremacy, largely targeting Aboriginal children considered “half-caste” due to their lighter skin color, and hence perceived as more receptive to settlement amongst white communities. Hence, as a deeply racially-motivated and insidious practice, Australia’s national policy encouraged the “dying out” of its indigenous community. The Stolen Generations constitute the Aboriginal children affected by removal policies.

The effects of historical disenfranchisement, silencing and marginalization of the Aboriginal community continue to be seen today. National policies of assimilation were a conscious, calculated attempt to disrupt the Aboriginal community; such policies achieved their goals. The brokenness of the Aboriginal community has resulted in disproportionate, all-time highs of indigenous children in the foster care system. Further, the indigenous community remains excluded from accepted ideals of the “Australian identity,” lacking acknowledgment in national day celebrations, the national flag and national anthem.

In 2008, then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd offered the first formal apology to the Aboriginal community, accounting for previous government policies which saw over 100,000 indigenous children removed from their homes. Ten years after this apology, however, an extension of former policies is noticeable through the increased assignment of Aboriginal children into foster care. Today, more indigenous children are being removed from their families than ever in history, with numbers almost doubling a decade after Rudd’s apology.

Statistics show that indigenous children are 10 times more likely to be placed in out-of-home care than non-indigenous children — and once separated, 40 percent of Aboriginal children will be placed within the care of non-Aboriginal families. The idea of the extended “Stolen Generations” arises from this disproportionate approach to foster care, which continues the cycle of assimilation, as Aboriginal children are removed from, and deprived of their culture.

Today, the increased number of indigenous children in foster care can be attributed to historical and systematic divisions within the Aboriginal communities. The historical treatment of Aborigines has resulted in socio-economic disadvantages which atypically plague the indigenous community, such as restricted access to healthcare, public education and social services, high levels of drug use, domestic violence, and isolation of indigenous communities. Furthermore, the Aboriginal community remains divided on their approach to foster care. Whilst some argue that separation is the best way to accommodate indigenous children at risk, others argue that increased removal from their communities only deepens emotional trauma and disconnect. Furthermore, the separation solution ignores fundamental issues within the Aboriginal community that leads to at-risk home environments. Walter Shaw, the chief executive of the Tangentyere Council which provides services to indigenous people in Central Australia, argues instead that kinship is the solution. Shaw asserts that strengthening Aboriginal communities through social and economic security would not only reduce the number of at-risk cases for indigenous children, but also equip Aboriginal families to be effective caretakers within the foster care system. The disproportionate representation of non-indigenous caretakers only increases the prospect of assimilation, and the salience of cultural division.

The Stolen Generations represented an insidious attempt to eradicate indigenous communities. However, practices of silencing, marginalizing and disenfranchising Aboriginal peoples remains the backbone of Australia’s social and cultural fabric. To most Australians, January 26th marks a day of celebration, as families unite for “Australia Day” festivities around a traditional barbecue and beers. Yet, whilst Australia’s national day represents festivities to some, it is also a harsh reminder of the nation’s violent colonial past. January 26th, 1778, was anything but a day of celebration for Aboriginal communities – instead, it marks the arrival of Britain’s First Fleet and the colonizers who came with it. Robin Thorpe, an Australian-Aboriginal man, recalls “If it wasn’t for their [British colonizers] acts of terror and their policy of genocide, Australia wouldn’t exist.” To Thorpe, Australia Day is “Invasion Day.”

The lack of visibility of the Aboriginal community extends to other key manifestations Australian nationalism – particularly, the national flag and anthem. The flag is a testament to the country’s sustained colonial legacy, containing the British Union Jack in its left-hand corner. Despite the long-standing debate as to whether indigenous elements should be incorporated into the flag, the Union Jack remains unchanged. Australia remains one of the few countries to contain another nation’s flag within their own. Additionally, the largest star on the flag is symbolic of the Commonwealth, and is referred to as the “Commonwealth” or “Federation Star.” This too denotes Australia’s explicit and proud ties to the United Kingdom through a continued of colonization.

Likewise, the national anthem, “Advance Australia Fair”, continues the trend of ignoring Aboriginal communities. The opening lyrics, “Australians all let us rejoice for we are young and free”, undermines and diminishes the history of indigenous peoples, depicting Australia instead as a new, young nation – born out of British colonization. With no recognition, or even allusion to Aboriginal peoples in any of the anthem’s lyrics, Australia’s national anthem ignores the 65,000-plus years of indigenous civilization that so shaped Australia’s landscape.

From the Stolen Generations to today, Australia’s Aboriginal community represents a Stolen Peoples – separated from their communities, culture and contribution to Australia’s socio-cultural fabric. Today, this warrants the question of who gets to be acknowledged as an Australian. As long as the indigenous community remains excluded from manifestations of Australian nationalism, Australia’s Aboriginals are denied claims to a national identity. As long as Aboriginal children are continuously placed in foster care, instead of drawing attention to the systematic fragmentation of the Aboriginal community, Australia’s Aborigines become increasingly divided and dispersed.

Without acknowledging these nuanced efforts to marginalize indigenous peoples, the historical disadvantages to the Aboriginal community cannot be reversed. Can Australia afford to wait another century before acknowledging its past wrongdoings, in the same way it took up to 50 years for a national apology for a century of Stolen Generations? If this is the case, Australia’s first people will soon become Australia’s Stolen Peoples — and how ironic that would be.

Featured Image Source: CNN

Be First to Comment