In June 1949, a few months before emerging as the victor in a trailing civil war, Mao Zedong articulated the two pillars that would embody the new system of governance: a “domestic united front under the leadership of the working class” that would lay a foundation for “people’s democratic dictatorship” and an international alliance with other “revolutionary” governments in Eastern Europe, namely the Soviet Union, that would bring an ultimate triumph to proletarians.

Having celebrated its 70th birthday in October 1st, the Chinese Community Party finds itself leading a strikingly different country than the one its founders first envisioned. Contrary to Mao’s vision, entrepreneurs and capitalists have been the ones to sustain the nation in the past three decades while farmers and laborers have found themselves increasingly marginalized.

The contrast is even more remarkable given the historical backdrop. Mao’s ambition to build a competitive collective state upon the two pillars soon stuttered: his major domestic agenda suffered a series of debacles — namely the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution that upended China’s economy and society. His camaraderie with the USSR soon dissipated as well; Mao and his successors came to deplore the Soviet Union as “revisionist,” claiming that China was the only country in the world in which Marxist ideology was left untarnished.

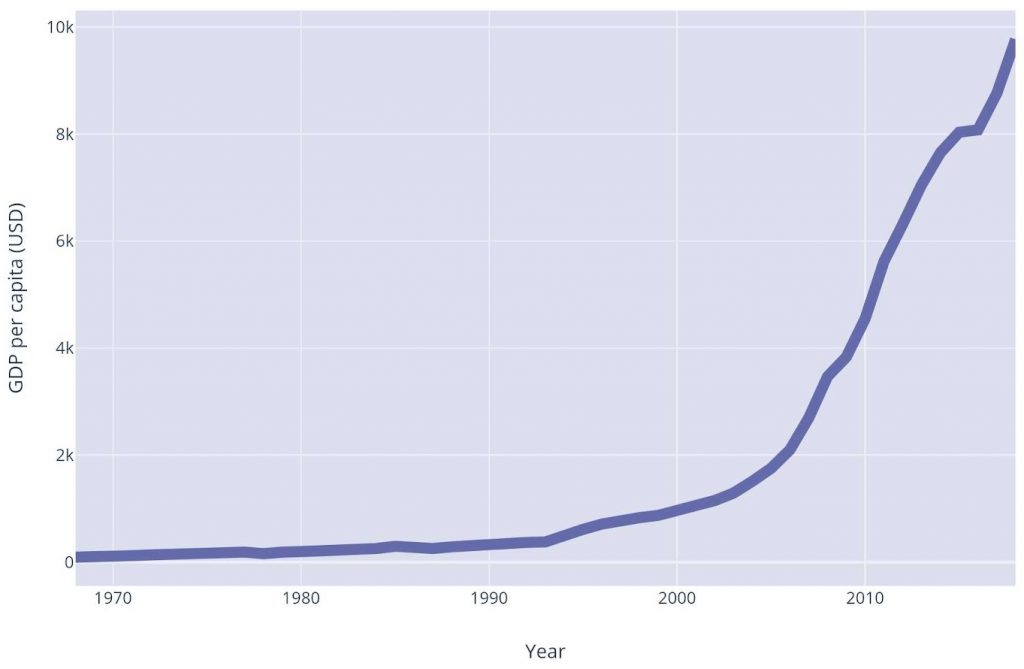

Hence the great irony: when the Eastern Bloc deceased in the late 1980s, China emerged as the only economically robust nation by ‘revising’ the most and discarding its purist pride. Following the death of Mao in 1976, Deng Xiaoping sought to recover his devastated country by adopting gaige kaifang (“reform and opening”), which involved a rapid loosening of controls on industries, proactive pooling of foreign investments and granting of decentralization in policymaking. Inflammatory radical rhetorics that engulfed the country were soon replaced by calls for practicality, dubbed as socialism with “Chinese characteristics”. This volte-face nonetheless allowed China to ascend to global superpower in just three decades (see graph below). Today, China has the second largest economy, is the largest export destination for 33 nations and the largest import destination for 65; it attracts the second largest foreign direct investment (FDI) and has surpassed America in GDP (based on PPP) as a share of the global total in 2012.

China‘s GDP per capita, 1968-2018

At the same time, this very dramatic rise and transformation have begotten fundamental questions stemming from the widening disparity between the nation’s political facade and economic directionality. As China’s economy continues to grow at an eye-watering speed (in relation to its gigantic size), so does its dissonance with the global economic order spearheaded by the U.S. Pressure is mounting within the domestic economy as well. Seung-Youn Oh, an assistant professor of political science at Bryn Mawr College, claimed that the current dilemma the Chinese economy is facing is between the firms’ needs for further reforms to globally compete in a more propitious environment and the political leadership’s desire to strengthen its presence. Acutely aware of these tensions, Deng often used to emphasize perseverance to his colleagues by citing tao guang yang hui, an ancient idiom which means “concealing strength and biding time to hide one’s light”. The coincidence of the current premier Xi Jinping’s foray into openly expanding his country’s influence and reclaiming its role as a major global power, in parallel with Donald Trump’s reactionary protectionism, has only intensified the tension.

As a result, Xi is currently beleaguered by layers of conflicts that his predecessors had never encountered. China’s attempt to dominate 5G network through Huawei was forestalled by the American government on the grounds that its technology may function as the “backdoor” to transmitting sensitive information to the Chinese government. The Belt and Road Initiative is a $1.2-1.3 trillion transcontinental project to rebuild the Silk Road by connecting major infrastructures and is funded through China’s public and private loan across Asia, Europe, and Africa. It has received criticism that it not only seeks to expand its sway over countries by increasing their economic dependence on China (often called “debt trap diplomacy”) but also heightens regional financial instability by handing out loans to already debt-ridden countries. BRI may also affect China’s fiscal stability. Professor Gerard Roland of UC Berkeley’s Political Science and Economics departments argued that China’s “de facto subsidizing” of developing countries may backfire when the recipients commit to strategic default (the debtor intentionally defaulting in spite of solvency), transferring the onus on the Chinese firms and local governments.

China’s all-out hegemonic struggle with America has put an enormous strain on sources from which the Chinese economy has prospered. Although the Trump administration’s tentative tariff measures only account for 4 percent of China’s GDP at most, the protracted uncertainty has deterred investment and made foreign entrepreneurs in China take pause. A recent poll by the American Chamber of Commerce showed that about 40 percent of respondents said they are “considering or have relocated manufacturing facilities outside China.” This is even more painful on the Chinese part when labor costs have continued to rise over the past decade; Southeast Asian countries are enthusiastically bracing to establish themselves as the new center of ‘Factory Asia’. Most recently the standoff entered a new phase when China let RMB weaken past 7 against the dollar (widely known as the psychologically acceptable threshold), causing sell-offs in financial markets across the world. Considering the two countries’ economic heft, dispute between them is now tightly knit to the global economy.

Territorial issues only exacerbate China’s foreign tensions. The recent demonstrations in Hong Kong caused several western countries to urge China to guarantee liberty and abide by the “one country, two systems” arrangement. The event is also affecting Taiwan across the strait. Tsai Ing-wen, the incumbent president from Democratic Progressive Party that opposes close ties with China, is gaining popular support in response to the developments in Hong Kong. China has been criticized for unethical treatment of Uighurs in its so-called “re-education camps” in the Xinjiang region, where the question of independence has been long raised. Additionally, the South China Sea continues to be a source of military standoff, especially given the fact that defending the region is an integral part of China’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

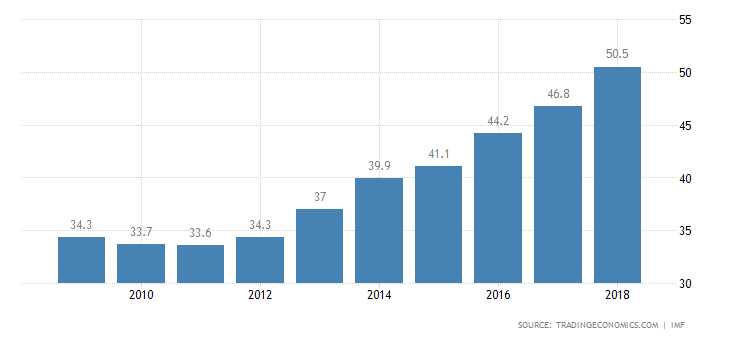

Momentum has to come from within. The Chinese government was able to cope well with the global financial crisis by using a number of enormous expansionary policies, allowing it to consolidate its economic power while other advanced countries stuttered. However, it also accelerated debt piling that has remained at dangerous levels in recent years. According to the Institute of International Finance, China’s total debt rose to 303 percent of its GDP in the first quarter of this year, a six percent year-on-year increase. At the same time, Professor Roland pointed out that because the Chinese debt’s dependence on foreign capital is low, the crux of the problem is “soft budget constraint” marked by the lack of financial discipline among local governments and state-owned enterprises (see graph below). Mounting debts nevertheless put the Chinese authority in an especially precarious position. In response to soaring debt levels, the Chinese government has pursued deleveraging by streamlining bad loans, overhauling capital flow tracking measures and urging local governments to retrench. Stimulus measures are in great need to rev up domestic firms’ growth against uncertainties abroad, yet they also run against deleveraging which is integral to stabilizing the economy. The monetary policymakers also face a similar dilemma: let the yuan weaken at risk of capital flight or defend it at the risk of strangulating the exporters.

China’s Public Debt as % of GDP, 2009-2018

(Source: Trading Economics)

While rupturing sounds abound, the CCP’s task of maintaining both political and economic stability simultaneously is becoming more challenging than ever. The inherent conflict manifested itself in fierce protests that have recently occurred in Hong Kong: although it was an extradition bill that kickstarted the demonstrations, the changing demands of the citizens show that the stakes are far more profound and deep-rooted.

For the past four decades, wholescale compromises to its ideological commitment have been accepted thus far under a thriving economy. Graham Allison, a professor of political science at Harvard University, argued in his book Destined for War that “performance justifies one-party rule”. The bold reforms indeed reversed the path China was destined to walk if it were to firmly hold on to Maoist policies. At the same time, they also have eroded the government’s hold on different aspects of society. This is even more irreversible in an era of internet and technology. About four months ago, the government took great pains to ‘smoothly’ pass the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Protests, in which youth gathered to call for an end to corruption and the restoration of democratic freedom but were brutally suppressed. Similarly, the situation in Hong Kong accelerated when a teenager was shot on the National Day. With all eyes fixated on the city, it looks preposterous for the CCP to replicate the way they responded thirty years ago.

Against all these odds, China’s government may successfully cope with these challenges in the coming years. Its growth rate in the second quarter was 6.2 percent, the lowest since 1992, but incredibly impressive for an economy with 1.4 billion people. Having lifted 800 million people from poverty, the party still has a strong appeal to its people. However, in a time in which China is redefining its position in the global order, the country now has to answer questions that seemed tangential in the past. In a recent meeting for CPPCC, a consultative body, Xi emphasized the need to delineate “the relationship between uniformity and plurality,” calling for the former in political foundation while the latter in benefits and ideas. Whether his fellow Chinese and foreigners interpret the CCP’s future trajectory in the same way will be crucial for his party in the upcoming years.

Featured Image Source: Berkeley Political Review Design Team

Be First to Comment