California is the second-biggest state by landmass and the first largest in terms of population; with almost 40 million residents, the Golden State is home to more than 12 percent of the United States’ population. This has made the state a liberal powerhouse on the national stage and has allowed its state legislature to be dominated in recent years by a strong Democratic majority. However, some residents of the state would rather sacrifice that federal influence for a further streamlined and more manageable group of smaller states. At its core, this stems from a desire to have states remain more faithful to their respective constituencies than the Great Golden State is able to be at present.

For almost as long as California has existed, there have been movements to partition it into smaller pieces, with the boundaries of the new states as varied as the justifications for doing so. The Pico Act of 1859 was the first to try, occurring a short 9 years after California attained statehood, in order to escape what was at the time perceived as unfair taxation and land use legislation. Since then, there have been over 200 attempts, not without cause. The state’s growth has been unprecedented, and the geographic concentration of rural and urban populations facilitate a representation that can leave something to be desired. This rings true for many of the state’s conservative populace, who take issue with the domineering manner this legislatively liberal agenda is pushed.

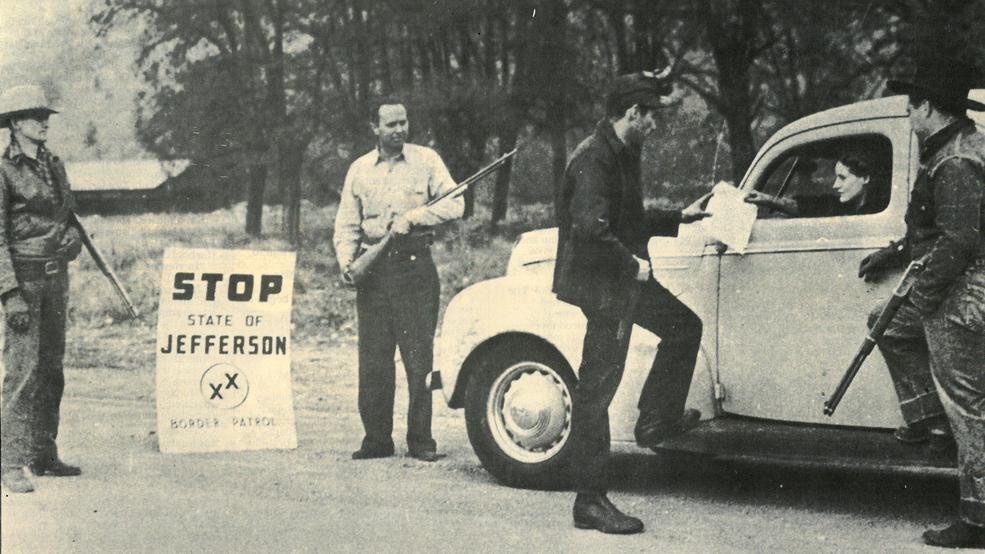

The state of Jefferson has perhaps been the most notorious and enduring of the state-secessionist movements, speaking to this sentiment of discontent. First proposed in the early 1940s and characterized by highway protests, this hopeful 51st addition to our Union would see northern California split off into its own state. While borders have varied over time, and in the past have included swathes of southern Oregon, the boundaries espoused by organizers in present day have largely concentrated their efforts to dismantling the Golden State. Modern boundaries start at the top of our current state and extend down to Tuolumne county at its south-most point, carefully carving around more liberal areas like Sonoma and Sacramento. Even discounting their Oregonian counterparts, the counties counted among those who formally submitted their intention to leave California have a population significant enough to render them the 39th largest state, if successful.

This most recent iteration emphasizes the political and economic stifling of its residents as the primary reason for pushing the new state, with some notable examples being a desire for “liberty,” “property rights,” and greater representation. While California on the whole is often described both by supporters and critics as something of a liberal haven, the populace of this proposed state leans sharply to the right. Republicans outnumber Democrats by almost 90,000 registered voters, and party loyalty is no joke in these parts, with residents supporting Trump over Clinton in the 2016 election 53 percent to 39 percent. Of the 24 counties that voted to elect President Trump over his opponent, 19 of them were located within Jefferson’s proposed borders. This stark bastion of red situated along a coastline of blue is tired of having its voice drowned out by a sea of strong liberal sentiments, and its desire to be heard is the driving force behind the movement. The large X’s featured on their proposed flag, and seen in the images above, speak to this driving force; they represent the times the region was “double crossed” by California and Oregon, respectively.

However, while its fight for meaningful representation is understandable, many of its justifications outside of this ideological realm lack much depth or nuance. The movement’s leaders and website offer a slew of reasons, under such broad categories as “regulations” and “restoration,” which vary wildly in validity. One notable instance is their claim that California’s “property taxes are 10th highest in the nation,” despite the state’s property tax rate being ranked as only the 34th highest at 0.81 percent in 2015. Other issues they claim to fight to resolve are vague, such as “revamping Social Services” and advocating for “constitutionally based laws,” and lack much further explanation.

In spite of many of its central tenets relying on misinformation, the movement resonates enough with the people of this northern California region to grant it more success than previous iterations. Trump’s fiscally conservative promises were not the only thing that resonated with Jefferson’s residents and movement organizers.

While Californians living south of Sacramento might be unfamiliar with the proposal, residents of the area are well acquainted with the idea. Although this movement is decades old, it has recently regained traction, with modern secessionist statehood groups successfully lobbying many of the counties included in the proposal into passing declarations of intent to exit the state; despite being a relatively modern revival, juris coordinator Mark Baird considers 21 counties supportive of the separation, either through local governing bodies or county votes. It is pertinent to note that 2 of these county declarations were later rescinded, and 3 of the counties counted on the movement’s website as being in favor had the measure explicitly shot down by their county government. Despite being a movement largely built upon pillars of fair representation, it is an interesting quirk that its founder and website fail to reflect these dissenting changes.

All circumstances considered, it seems unrealistic that this 51st addition to our nation will come to fruition at present. Californians overwhelmingly disapprove of the measure, with 59 percent of voters opposing, 25 percent in favor, and 16 percent holding no opinion. With those numbers, even if organizers took on the mammoth task to convince the neutral voting population, they would still be outnumbered by those opposed. Tellingly, the idea fares significantly better among California’s Republican voters, who on the whole favored the creation of this new state at a rate almost twice as high as their Democratic counterparts. Support was understandably highest in the Northern region of California where the movement grew out of, which saw 41 percent of voters in favor.

While the Jefferson movement may be controversial among residents, this secessionist desire is not unique to the state’s conservative population alone. There are those who consider themselves staunch liberals that have pushed for a reconsideration of the state’s composition. One such individual is Timothy Draper, a billionaire venture capitalist from Silicon Valley, who has pushed multiple split-state initiatives over the past few years. The first was the Six Californias proposal, a measure which sought to create a more governable grouping of states. Although much funding was invested in the initiative, it failed to meet the signature threshold to qualify for the ballot in 2014. Not one to be discouraged, Draper recently resurfaced with a similar proposal entitled the California Three States Initiative in 2018, more commonly referred to as CAL 3. This movement instead advocated for dividing the greater Los Angeles region from that of Southern California, and from separating both from a Northern California which begins at the Bay Area.

California voters almost had the product of Draper’s labors grace them last November in the form of Proposition 9, which was initially placed on the ballot after receiving over 600,000 verified signatures. Despite the not-insignificant media attention Draper has managed to attain, it is doubtful either of his measures would receive nearly as much attention without the influence awarded to him as a wealthy venture capitalist. Because of the signature threshold necessary to put a measure on the state’s ballot, initiatives that don’t already have widespread support from the voting populace and a mobilized base organizing around them have little chance of being considered come November — that is, unless they have enough funding to compensate for a lack of enthusiasm.

If an issue is not inherently pressing enough to the population to galvanize residents to organize around it, then more often than not it ends up on the ballot because those who are most invested have enough money to push their agenda on the rest of the populace. Fortunately for the CAL 3 movement, Draper is one such individual; he is not the first of his name to find success within venture capitalism and investment banking, following in the footsteps of both his father and grandfather.

In spite of garnering more support than its predecessor, the CAL 3 initiative was ultimately blocked by California’s Supreme Court from partitioning California this November for precisely the reasons it could be considered a politically strategic initiative. Under the current deeply partisan Congress, the body politic would largely balk at the thought of tripling California’s representation; particularly given how the one reliably conservative constituency of the North, given its own voice in Draper’s previous proposal and the Jefferson movement, would be lumped in with the significantly more populous Bay Area.

In fairness, he does raise some valid reasons to consider a split state. Although California has significant power in the House, it stands at a significant disadvantage within the Senate, where it is granted as many members as states with just a fraction of its population. However, it is clear from his past rhetoric that his proposal uses regional patriotism to fuel the desire for secession among frustrated constituents without actually considering the best interests of all Californians. He previously criticized a 3-state solution, believing it too similar to the current iteration of the state wherein “(Californians would) end up with the same kind of environment, where you’d end up with two monopolies or three monopolies.” He seems to have since changed positions on this matter in the brief 4-year period between proposals, given the fact that CAL 3 almost found itself on the ballot this past election cycle.

Additionally, much of California’s political power comes not from its representation in Congress, but from the soft power and standing it holds as the state with the highest population and GDP. Splitting California up into pieces would threaten these factors that facilitate its influence. Draper and many who share his sentiments largely set up their argument on the grounds that California, for all its massive industry and population that has lead to its importance domestically and abroad, has rendered it “ungovernable.” What many organizers mean when they say this is not that our state officials, elected or otherwise, have descended into unorganized chaos; rather, policymakers are pushing agendas that do not reflect the personal interests of these outspoken dissenters. For while both of Draper’s proposals speak to this discontent, lurking behind his rhetoric about more authentic representation is a desire to separate the wealthier urban areas of the state from their rural counterparts.

Their efforts would be better directed toward organizing around the specific issues they see in the current state and trying to improve conditions for all residents. Trying to shape a new state in a manner that satisfies the political inclinations of a niche group of the population is disingenuous to the ideology that American democracy was founded upon.

The people of California deserve representatives that fight for their best interests, whether that be on the local, state or federal level; holding these elected officials accountable to the needs of their constituencies can help ease some of the tension wrought from living in such a massive state. Expanding the number of seats in California’s legislature, which has not increased since 1861, would similarly address the heart of this issue.

For all the complications that California’s diversity of industry, values, population, and resources create, they are ultimately what make it such a culturally and historically rich place to live. Dividing it for petty, selfish, or uninformed ideological differences, particularly those that could be addressed by more effective local and state representation, would be an unjustifiable sacrifice.

Featured Image Source: Siskiyou County History Society

Be First to Comment