In the span of three years, from 1986 to 1989, the Iraqi Military Force killed between 50,000 to 182,000 Kurds and destroyed 90 percent of all Kurdish villages in Northern Iraq. This dark episode in history is often referred to as the Anfal Genocide. As the persecutions against the Kurds continued in Iraq, many sought political asylum in Europe and the U.S. One of these political refugees is Bar Aziz, a full-time software engineer currently residing in Nashville, Tennessee.

Mr. Aziz migrated to the US during the last months of 1997 alongside 2000 other Kurdish individuals. He and his family were forced to flee Iraq because they supported the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan during the Kurdish Civil War (1994-1997). Once the war ended, even though a cease-fire was agreed upon and two regional Kurdish governments were created, they felt that their livelihoods were at risk under Saddam Hussein’s regime. Yet even after more than 2 decades in the United States, Mr. Aziz’s Kurdish roots remain a core aspect of his identity. Outside of his day job, Mr. Aziz is a board member of the Tennessee Kurdish Community Council, which helps preserve and promote Kurdish cultural heritage in the United States.

“A fully independent Kurdish State is the only possible way to stop the persecutions, to end the tragedy in the Middle East,” said Aziz. “It is the only possible way that the Kurdish people can ever feel safe.” He then adds, “ A free Kurdistan is every Kurd’s dream.”

A free Kurdistan is every Kurd’s dream

Yet in order to truly comprehend the meaning and the impact of Mr Aziz’s words, we must understand who the Kurds are, their role in Middle Eastern politics and the regional implications of their longstanding fight for independence.

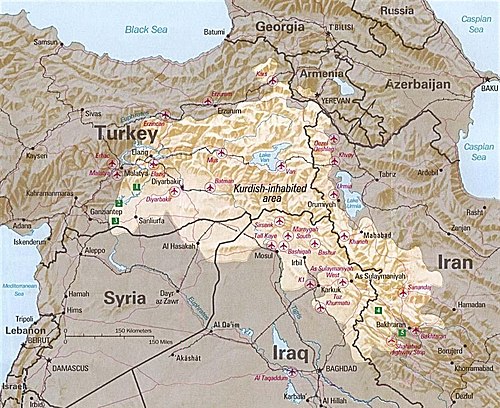

Source: US Central Intelligence Agency

Since the First World War, the story of the Kurds has been a mixture of tragedy, confusion and hope. The Kurds are the largest ethnic group in the world without a nation-state, with approximately 45.6 million Kurds living all across the globe. The majority of the Kurdish population, however, is concentrated in the mountainous regions of southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq and Syria and northwestern Iran. Although not recognized by the international community as an official state, this region is commonly referred to as Kurdistan: the land of the Kurds.

In the Middle East, the name ‘Kurdistan’ alone has the capacity to ignite arduous debate. For many, it represents a threat to their country’s sovereignty and nationhood. For the Kurdish people, however, Kurdistan represents a place of acceptance and belonging — a homeland. Kurdistan, and particularly the idea of an independent Kurdistan, has been a source of political instability and ignited armed conflict in many countries. Yet who exactly are the people advocating for an independent state? When and how did the idea first appear? What is the Kurdish sentiment on independence? What is the international sentiment on independence? Finally, are the Kurds actually stateless?

For more than a millennium, the Kurdish people have been living in this mountainous region of the Middle East, referred to as Kurdistan, under the dominance of the Safavids and the Ottomans. Throughout this period, Kurdish tribal leaders have led multiple rebellions for more autonomy within the empires, but these rebellions were always suppressed by the central authority.

Kurdish nationalism, however, rose in the 19th century and was reinforced during the First World War. In fact, the British Empire, while fighting against the Ottoman Empire, promised the Kurdish people their own nation-state if they fought alongside the British. This offer was accepted by the Kurds. Hence, when the Allied powers won the war, the Kurds thought that their everlasting dream of an independent Kurdish State would finally come into existence. Indeed, the Treaty of Sevres signed in 1920 between the Allied forces and the Ottoman Empire provisioned a Kurdish Nation State in southeastern Anatolia. Yet in 1923 the Republic of Turkey was founded and a new treaty — the Treaty of Lausanne — was signed. The Treaty of Lausanne had no mention of a Kurdish nation state. Hence the Kurdish people were scattered across four different countries.

Since 1923, several Kurdish political parties, separatist movements and armed military groups have formed in the region. The central governments of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey have frowned upon almost all Kurdish political entities. Nevertheless, Kurdish political parties and military groups are key actors within the region — particularly the Kurdistan Democratic Party and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan. Both of these political parties, which are currently based in Iraqi Kurdistan, have advocated for an independent Kurdish State. Indeed, in 2017 a referendum was held in Iraqi Kurdistan asking the population if it supported an independent Kurdistan or not. An overwhelming majority — 93 percent of the voters — voted yes for an independent Kurdistan. Yet two years later, Iraqi Kurdistan still remains an autonomous region within the Iraqi State. So, why is a Kurdish nation-state of any size so difficult to obtain?

First of all, it is important to understand that the Kurdish nationalist movements play out differently within each country. Not only are the Kurdish populations among different countries are culturally divided but they are also represented by different political groups. Moreover, the outcome of the Kurdish independence movement varies within the context of the national policy of each country. For this reason, the realization of a greater Kurdistan is a very improbable phenomenon.

Source: US Central Intelligence Agency

According to Peter Bartu, a lecturer at UC Berkeley on political transitions in the Middle East, the Iraqi Kurds are arguably the ones who are best placed for independence. Yet even for them, independence doesn’t seem possible in the near future because they lack political unity within Iraqi Kurdistan. Since 1991, Iraqi Kurdistan has been split into two regions: the west, surrounding the governorates of Dohuk and Erbil, controlled by the K.D.P. and heavily influenced by Turkey; the East, surrounding the governorate of Sulaymaniyah, controlled by the P.U.K and heavily influenced by Iran. This power divide among Kurdish nationalists has been the main cause of the Kurdish Civil War between 1994-1997. And it continues to hinder the will of the Kurdish people. Peter Bartu states that the relationship is becoming worse and that it’s not clear if they can emerge out of this situation.

“They have a couple of big challenges in front of them,” said Bartu. “Their reserves in natural gas and oil in Iraqi Kurdistan are so big — beyond anyone’s wildest dreams — that it’s driving them all mad because they don’t quite know what to do with them. This feeds into the rivalry between the two branches and makes it harder for them to agree on policies vis-a-vis Baghdad, Turkey, Iran and also with the rest of the world.”

Even though the Iraqi Kurdistan region is very rich in terms of natural resources, the Iraqi Kurds have a debt of 17 billion dollars, more than 300 percent of their annual revenues. This debt is partly due to corruption. In fact, Iraqi Kurdistan’s Energy Ministry is one of the most opaque in the world. The final destination of most of the money generated through the sale of oil is unknown. Hence, it would not be wrong to say that the Iraqi Kurds have been let down, first and foremost, by their own politicians.

According to Bartu, “this colossal economic mismanagement and the lack of political unity have indeed suppressed the indomitable fire of Kurdish nationalism.”

Nonetheless, on the world stage, sympathy for the Kurdish independence movement is growing, especially after the People’s Protection Units’ (Y.P.G.) fight against I.S.I.S. in Northern Syria. Throughout the war, the western press has glorified how the Kurds protected non-Muslim minorities and how women occupy significant roles in Kurdish militia groups. However, Bartu urges us to be cautious about the ‘myths’ surrounding the Kurds in the media. The treatment of women remains a significant problem within the Kurdish community. According to many reports, honor killing rates are extremely high among the Kurdish population. The U.S. Department of State’s 2014 Country report states that between January 2014 to May 2014 there were 100 cases of ‘women burned down by others’. According to the 2018 Iraqi Kurdistan country report published by the Danish Immigration Services, many honor killings are registered as ‘something else, for instance, suicide’.

This colossal economic mismanagement and the lack of political unity have indeed suppressed the indomitable fire of Kurdish nationalism.

Alongside the conservatism within the Kurdish population, the international media seems to almost always neglect the idea that the central governments of these four countries can be beneficial to the Kurdish people. Bartu calls this phenomenon “the ties that bind”. The peripheral areas, especially in Iraq and Turkey, benefit from having politicians in the capital and being represented in the parliament. In fact, the Iraqi president, Barham Salih, is of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan Party. For this reason, the Kurdish elite is sometimes reluctant to further the cause of independence. After all, they are bound to the central government through economic and social interests. The average Kurdish citizen living in the periphery also benefits from this bond. Hospitals, roads and schools are all built in Kurdish provinces through state funding.

Overall, an independent Kurdistan does not seem to be happening any time soon. The lack of unity within Kurds themselves, combined with corrupt politicians and opposing foreign states has brought the Kurds’ fight for independence somewhat to a deadlock. Nonetheless, the desire for sovereignty endures within the Kurdish population — especially in that of Iraq.

The years to come will show if the Kurdish people can trace their own fate and fulfill their everlasting dream for independence.

Featured Image Source: Levi Clancy

Be First to Comment