In July of 2019, Boris Johnson defeated numerous moderates within his own Conservative Party to become the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Political pundits immediately called him a lame duck. He had no mandate, no working majority and no realistic plan to pass Brexit, which loomed ominously over his premiership after destroying the careers of his two immediate predecessors. After numerous MPs defected from his meager coalition, some commentators suggested that Johnson’s term in office would end up being the shortest in the modern history of the UK. His government, many said, was teetering on the brink of a vote of no confidence.

Less than a year later, it’s hard to believe that these gloomy prognostications for Johnson’s premiership once seemed reasonable. In December’s snap election, the Conservatives won a landslide victory, winning seats they hadn’t held for decades and forcing the resignation of two other major party leaders. Johnson quickly used his newfound majority to push through the Brexit deal that had eluded Theresa May for her entire tumultuous term in office. The seemingly endless debacle of Brexit negotiations was suddenly brought to an end. The pundits were wrong again — just as they had been about the initial Brexit vote in 2016.

The United Kingdom officially left the European Union on January 31, 2020 — over three and a half years after the referendum. But those who simply wish to put this painful chapter in British political life behind them may be disappointed. The ramifications of Brexit, ranging from the Irish border to a possible second referendum on Scottish independence, will be felt well into the future. Johnson’s term in office will last several years, and whether he is a trustworthy steward of post-Brexit Britain remains to be seen.

But even as Johnson tries to look forward, unanswered questions remain about the past. Why did millions of Britons feel so compelled to upset the global political order in 2016? Why were so many people so willing to throw a wrench into the cogs of the European Union? Did the message sent by voters in the referendum have the desired effect? And most importantly, was it worth it?

No Consensus and No Compromise

There is no one reason why the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016. The referendum was presented to the public as a black-and-white, yes-or-no issue, leaving voters with very little room to communicate why they chose Leave or Remain. Because of this, it became difficult to gauge which Brexit approach had a democratic mandate following the narrow results of the referendum — a problem that was exacerbated after the 2017 general election, in which the anti-Brexit Labour Party made significant gains at the expense of the pro-Brexit Conservatives. Both the Leave and Remain camps could now credibly claim to represent the will of the people, and so the Brexit process came to a grinding halt.

During this period of foot-dragging, some pro-Leave factions suggested that the Remainers were “undermining democracy” by refusing to abide by the results of the referendum. The Remain side, meanwhile, floated ideas of holding a second vote on the issue. This was a dangerous proposition, and it raised fears that pro-EU factions would repeatedly hold new referendums, relying on voter fatigue to eventually get their preferred result. Other ideas included a new referendum asking for the type of Brexit plan voters most preferred or another snap election.

Part of the problem was that the British political establishment didn’t understand what voters wanted. The Leave campaign used vague phrases like “Take Back Control” to great electoral success but spent very little time detailing what the Brexit process would look like. Aside from MPs Boris Johnson and Michael Gove, few prominent members of the Leave campaign held elected office, and no comprehensive plan for Brexit had been developed. With no foothold in the government and no consensus among pro-Leave factions as to what Brexit should look like, the Brexit process quickly became rudderless — a problem exacerbated by PM David Cameron’s immediate resignation following the referendum’s results.

But if the establishment didn’t know what voters wanted, it was partly because the voters themselves didn’t know. Voters had wildly different reasons for voting Leave and had similarly divergent views as to what Brexit should actually look like. Immigration, health care and Turkey’s potential EU membership were all used by the Leave campaign to stoke anti-EU sentiments.

Paul Cheney, a U.K.-born professor of political science at the College of Marin, finds factual flaws in all of the Leave camp’s arguments. “The Leave campaign said that the United Kingdom sends £350 million a week to the EU,” says Cheney, referring to a figure that was prominently featured on the Leave camp’s famous red campaign bus. “But that number is misleading; it’s the result of rearranging financial figures. And of course, the EU sends some of that money back for farm subsidies and youth centers. A massive amount of British infrastructure was paid for by the EU.”

Pro-Brexit groups argued that this £350 million sent to the EU could be redirected towards Britain’s National Health Service, the N.H.S. But as Cheney points out, the impetus for the decline of the NHS was domestic policy, not EU policy. “During the financial crisis, David Cameron introduced austerity measures,” Cheney says. “Youth centers shut down, libraries closed and the health care system was not supported. People were disillusioned, and they blamed the EU. But it was the Conservative Party’s policies that hurt the NHS to begin with.”

Another selling point to voters was the fear that Turkey might join the E.U. in the near future. When asked if this is likely, Cheney laughs.

“Turkey has been negotiating to be part of the EU since the 1960s,” he says. “There are many Christian political parties in Europe that see the EU as a Christian project, and they don’t want to see Turkey join. Turkey tried everything it could to get into the European Union, but they saw the entry of Cyprus as the last straw.”

EU membership requires a 100% consensus from all other member states. Cyprus (which has been on poor terms with Turkey since the 1974 Turkish invasion) would never vote to allow Turkey to join, effectively rendering the entire argument moot. “The fearmongering over Turkey during the referendum speaks to how easy it is to manipulate people,” says Cheney.

And here we have the reason for Brexit’s repeated delays. When the margin of victory for Leave was so narrow, and when so many of the campaign’s arguments were based on misinformation, it became impossible for policymakers to design a Brexit strategy that would not alienate a majority of the country. If voters were expecting a new influx of money to the NHS, they wouldn’t get it. If voters were expecting a cutback to immigration, they wouldn’t get that either — many of Britain’s immigrants come from the former Commonwealth, not the EU. And if voters were concerned about Turkey’s membership to the EU, that was a pipe dream that was phenomenally unlikely in the first place.

In multiple ways, the process of Brexit may have been destined for disarray before it even started.

Boris Bites Back

The 2016 referendum, though divisive, was only a harbinger of the political chaos to come. After David Cameron resigned, Theresa May won the premiership in a leadership election within the Conservative Party. May promised to honor the results of the referendum and deliver Brexit quickly, though her credibility was somewhat tarnished by the fact that she was originally on team Remain.

As the negotiation process began to stall, May made a serious miscalculation. In an effort to gain more seats and obtain a clear majority in the Parliament, she called for a snap election that proved disastrous for May. The pro-Remain Labour Party, headed by Jeremy Corbyn, gained enough seats to deprive the Conservatives of their majority, forcing them into an even weaker coalition government.

Milton Zerman, a former Berkeley ASUC senator and Eurosceptic, was in London the day of the referendum. “Their big mistake was not going with Johnson immediately instead of Theresa May,” he says. “If they’d done that, a lot of this could’ve been avoided. People were not enthusiastic about her. They were about Boris.”

Looking back, it does seem that Theresa May’s premiership died the day of the 2017 referendum. With a weak minority government and a parliament that rejected every Brexit deal she brought to the table, she was running on fumes. In the summer of 2019, May resigned in a frustrated, tearful speech. The Conservative Party desperately needed a charismatic leader — one who had been pro-Leave from the start and who could credibly speak to the perspective of the Brexiteers.

They found him in the former Mayor of London, Boris Johnson.

Johnson got his political start as a journalist in the 90s criticizing the E.U. But when the time came to take a side in the 2016 referendum, he waffled for weeks. “Those who know him privately tell us that went back and forth on the decision dozens of times,” Cheney says. “Sometimes he’d change his mind multiple times within the same hour.” Johnson finally came down on the side of Leave, though not before making what he called a “pros and cons list” for and against Brexit. To many observers, Johnson’s decision was less the result of genuine conviction and more a method of raising his personal profile. His opponents denounced him as a political opportunist.

But ultimately, Johnson’s optimistic rhetoric about Brexit and unique personal appeal won him the leadership election, allowing him to take the outgoing May’s place. His premiership was immediately compared to the presidency of Donald Trump (both Johnson and Trump rode populist waves in 2016, and just as importantly, both have immediately recognizable hair). But to equate Johnson with Trump is to seriously underrate him as a political actor — although he adopts a bumbling persona in public, Johnson is a well-educated debater and a cunning career politician. Prone to waxing poetic on Ancient Greece and quoting Churchill, he also makes a point to be seen jogging in football jerseys and offering tea to reporters from his collection of mismatched mugs. The fact that this Eton-educated former Oxford Union president has managed to portray himself as a relatable everyman is a testament to both his political skills and his genuine likability. And he is remarkably liberal as well — his climate initiatives would be considered borderline progressive in the United States. A carbon-copy of Donald Trump he is not.

Johnson, like May, risked his premiership on a snap election, this one scheduled for December of 2019. But although he too was facing Jeremy Corbyn, the political winds had changed. Corbyn was beset by allegations of anti-Semitism, and many within the Labour Party considered his policies too far left for the party’s base. Complicating matters was Corbyn’s personal neutrality on Brexit; as a Labour MP he had once been critical of the European Union, but he now found himself leading the (ostensibly) anti-Brexit party. Whereas Johnson campaigned on the straightforward slogan “Get Brexit Done,” Corbyn’s waffling approach failed to provide strong leadership in favor of the EU.

“Jeremy Corbyn comes from a leftist faction that is quite antagonistic to Europe,” says Paul Cheney. “He views the EU as a corporate structure designed for free trade, and quite at odds with his socialist policies.” Corbyn’s difficult position as Labour leader is a perfect example of how Brexit has cut across traditional party lines in Britain. Riven by internal disagreements, Labour put forth a middle-of-the-road plan to renegotiate the withdrawal agreement and then hold a second referendum. As a result, many hardline Remain voters abandoned the party for the more decisively anti-Brexit Liberal Democrats.

When the polls closed in the December snap election, Boris Johnson and the Conservatives had won their biggest victory since the Thatcher era. Conservative MPs won in constituencies that had voted Labour for generations. Finally, the problem of a democratic mandate had been fixed, and British voters had delivered a resounding verdict — although whether it was pro-Brexit or anti-Corbyn is up for debate. With this electoral shellacking, the Remain side (and Labour) was cowed into silence. Johnson quickly held a vote on his revised withdrawal agreement, which was approved by Parliament. Jeremy Corbyn, widely blamed for Labour’s defeat, resigned.

“Boris has always exceeded expectations,” says Zerman. “It’s going to take Labour years to recover from this, and he’s going to be in there for a long time.”

The Roots of Populism

Even if Brexit is now in the past, the divisions it exposed in Britain’s political fabric are far from healed. Economists are forecasting a dip in British GDP as a result of Britain’s departure, and the EU hopes to penalize Britain for exiting the union in order to discourage other member states from doing the same. On the political front, both major British parties split into establishment and populist factions during the referendum, and those divisions have created deep animosities and strange bedfellows.

But the most worrisome divide is, of course, the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland — which is now a border between an EU member nation and the UK. The complications of Irish citizenship were a major obstacle in negotiating a withdrawal deal. Should Northern Irish citizens retain the freedom of movement afforded to them by the EU? Should UK citizens with dual citizenship be considered EU citizens as well? How should border crossings be regulated? The problems are endless, and as with all the potential problems caused by Brexit, the Leave campaign failed to address them.

Along with Northern Ireland and the city of London, Scotland also voted to remain in the EU. There have been rumblings of a new independence referendum for the Scots since the 2016 Brexit vote, and EU leaders have promised to “Leave a light on” for Scotland. In doing this, they are tacitly encouraging the Scots to secede from the UK — an unprecedented attempt to undermine the unity of their former member.

Despite all this, Ireland will likely be the bigger problem. “If Scotland tries to secede from the United Kingdom and rejoin the EU, Spain may not let them,” says Paul Cheney. “Doing so would lend too much legitimacy to the Catalonian independence movement. But if Sinn Fein [the Irish republican party] becomes a dominant party in Ireland, then the condition for a hypothetical British re-entry to the EU will be a united Ireland. Johnson has sold out the Northern Ireland unionists.”

The complications arising in Northern Ireland cannot be stressed enough. Just 25 years ago, Ireland was embroiled in a brutal paramilitary conflict between pro-UK unionist factions and Irish republicans. The Irish border runs unmarked through farms, creeks, and country roads. Attempting to regulate it as an international boundary could prove impossible, especially at current levels of funding.

But when polled on the question of Northern Ireland, Leave voters say that they’d vote for Brexit all over again even knowing the problems it would cause with the Irish border. Over 60 percent of voters even say that they would vote Leave again if it seriously damaged the economy, and a plurality say they would still vote Leave even if they lost their own job. Some of this may be attributable to sheer voter stubbornness — a refusal to acknowledge a past mistake — but that explanation seriously oversimplifies the reasons that people had for voting Leave. The truth is that economic anxiety is reaching a tipping point in much of the western world, and the result has been an upswell of populist rage against an international system that many people think is rigged against them.

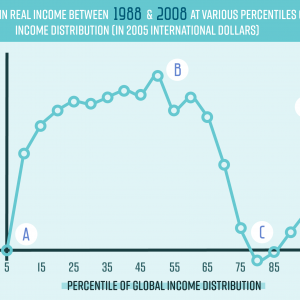

This graph, popularly referred to as the “Elephant Curve,” illustrates the distribution of income growth under the globalized economy. For the past 30 years, those in the “C” portion of the graph — largely comprised of the working class in Europe and North America — have experienced stagnant wages, and as a result have not reaped the rewards of the global economy. Instead, those gains have gone to two other groups: The global 1 percent (“D”) and the emerging middle class in East Asia and India (“B”). Due to the increased feasibility of outsourcing and automation, as well as more stable environments for international investment, the value of labor in the western world has been in decline for some time. At the same time, workers in Asia have seen their standard of living increase astronomically.

Given that Leave voters are willing to sacrifice their own financial well-being for Brexit, it may be misguided to pin the referendum’s results on economic anxiety alone. But financial insecurity can make voters act erratically, and when muddied multinational forces are at work, blaming a scapegoat like the European Union can be attractive. And Euroskeptics certainly have some legitimate concerns, even if they weren’t well-articulated during the referendum.

“The EU has a democratic deficit,” says Cheney. “The leaders of the European project are pushing for more centralized power and decisions made in Brussels, but people in EU countries don’t know who’s making those decisions. The assumption is that if everyone is happy economically, then they’ll be happy politically as well. And that’s fine — while it works.” With Brexit, it appears to have stopped working. Facing an economy that is gradually pushing them to the sidelines, many EU citizens (not just the British) have begun to view the Union as the instrument of their political and economic alienation.

The EU has also alienated nationalists in its member nations. Union courts can supersede national laws, and the EU has made efforts to establish a “European” identity by adopting a transnational flag and currency, both of which were met with considerable backlash at the time. The 2007 Lisbon Treaty, which further centralized EU power, also played into fears that a political union was being imposed upon member states. This political integration had a noble goal — to integrate Europe’s national economies to the point that another world war would become impossible — but while it has succeeded at diminishing animosity between nations, it may have amplified animosity within them. The new ideological battle is not between countries, but between insurgent nationalists and an internationalist governing elite. In short, the European project left the docks before making sure that everyone was on board.

You can’t put a price tag on national pride, and you can’t begrudge citizens their right to voice their economic woes by means of a democratic vote. While it’s easy to say that working-class Brits “voted against their best interests” in 2016, this condescending argument ignores the possibility that some people may genuinely value intangible concepts like national sovereignty more than their own financial well-being. And while the economic ramifications of Brexit could very well be a disaster, the alternative — refusing to honor the results of a democratic referendum — could have been far more damaging to Britain’s social fabric in the long run.

Featured Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Comments are closed.