As the weeks go by, and as we inch closer and closer to election day, both candidates Donald Trump and Joe Biden increasingly begin to finalize their political calculus and triangulate their most optimal stances on the issues in order to try and garner the most votes. Naturally, there has been much debate and rumination about Joe Biden’s campaign strategy; is he pandering too much to the left? Or is he leaning too far into the center to try to appeal to Republican voters? Some onlookers answer this dilemma by pointing to Bernie Sander’s nearly successful, intra-party coup, holding it up as evidence of the political expediency of Biden adopting a more left-leaning stance on the issues in order to tap into this pool of voters. Others argue that Biden should be wary to embrace this more progressive politic, for the Red Scare in America is far too great, and accomplishing a victory under such a banner would prove difficult.

In order to ascertain Biden’s proper path forward, we must come to realize this dilemma the campaign faces is not so simple as to be solely about trying to game voter demographics, but rather, that it is indicative of something greater, something larger at play. What we are witnessing, with the Biden campaign constantly trying to toe the line between these two voter bases, is representative of the establishment of the Democratic Party trying to grapple with the obsolescence and decay of what was, up until now, the uncontested governing paradigm; we are witnessing it trying to acquiesce its outdated politics with the death of neoliberalism, with the crumbling fall of the monolithic system which has heretofore governed the lives of millions of Americans every day. Consequently, how the party chooses to proceed will have far-reaching implications for the future of the party and, by consequence, the future of this country.

But in order for us to fully understand the import of this, first we must understand what precisely neoliberalism is — and this is no simple task. For it is an ideological constraint which has permeated into every notch of our society so much so as to be ubiquitous and, by consequence, invisible to the average citizen — therefore to elucidate its existence to the untrained eye requires a bit of legwork. And yet, there is certainly something absurd to this notion, for, as economist George Monbiot puts it, “to live in the United States … and not know what neoliberalism is, is akin to living in the Soviet Union and not having ever heard of communism.”

In its basest form, neoliberalism is an economic ideology which operates under the assumption that economic liberty and political liberty are inextricably linked. As such, it prioritizes maximizing the freedoms of the market and the private sector of an economy whilst simultaneously trying to minimize the public, governmental sphere; in order for us as a people to be as free as possible, neoliberalist ideologues argue, the market must be as free as possible. On a macroeconomic scale, this entails sweeping policies of economic liberalization, privatization, deregulation and the defangment of unions. In recent times, this litany of neoliberal structural adjustments has grown to include using tax-payer funds to provide generous corporate tax-breaks and subsidies to mega-corporations — which, although at first glance seems contradictory to neoliberalism’s commitment to a free market, is more than anything a continuation of this process of redistributing funds and power from the public sector to the private one.

In many senses it is something of a bastardization of the classical laissez-faire Liberalism popularized in the 18th and 19th century by political economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo — a doctrine the guiding principle of which was essentially that markets were completely self-regulating and that any government intervention should be avoided at all costs. By the late 19th century, however, this economic doctrine began to prove itself ineffectual. The completely hands-off approach to deregulation and the market had led to an obscene level of wealth inequality: according to the documentary The Gilded Age, the richest 4,000 families in the U.S. (representing less than 1 percent of the population) had about as much wealth as the next 11.6 million families combined. The economy collapsed in on itself in The Great Depression in 1929, in no small part due to the general instability that such an unequal economy lends itself to. I feel that it’s important to note here that in today’s America, we are seeing levels of inequality quite similar — or worse, really — to these figures from the Gilded Age: according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the top 1 percent in our country own as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, and this doesn’t even include the wealthy elites’ recent Coronavirus-induced windfalls.

As classical liberalism proved itself obsolete, it was supplanted by a different global economic paradigm: Keynesianism, modeled after the more interventionist-oriented teachings of renowned economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynes’ brand of economics was a stark departure; it advocated for the nationalization of weak industries, bolstering of unions, an expansive social welfare state, progressive tax reform and so on. This post-World War II period of Keynesian economics was one of unique economic equality and prosperity. Between 1951 and 1973, the world’s Real GDP Growth averaged 4.8 percent, and this growth never once dipped below 3 percent; in other words, during this time period, there was not a single recession. Further, income inequality was at far lower levels than it is today, and American society saw, as noted intellectual and activist Noam Chomsky puts it, “great egalitarian growth.” As a result, worldwide economic stability reached new heights, and people were freed up to participate in crucial social movements; it was, as many have referred to it as, the golden age of capitalism.

That is, until the stagflation caused by surging oil prices of the late 1970s offered a pretense for politicians to ditch these egalitarian, Keynesian policies; the circumstances had given the ruling classes an opening, a chance to reinstate their economic hegemony. Thus, it was then that neoliberalism (new liberalism) was born, under a Reagan administration which instituted sweeping deregulations, privatizations of government-run companies, and stark austerity measures. In the next election, Bill Clinton, rather than return to the Democratic party’s roots of championing workers rights, consolidated the neoliberal paradigm by continuing the deregulation of Wall Street through the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, et cetera, and further gutting welfare and public housing in what was a deluge of anti-poor legislation. Thus, the once discredited, ashen phoenix rose once more, and the second coming of a once considered defunct system, yet again, became the mandate of the Western world.

Up until Trump, both political parties had remained committed to this economic policy of neoliberalism. When one wiped away the faux veneer of multiculturalism of the Democratic establishment and the theological glint of the Republicans, in the end their economic imperative remained roughly the same. It is from this unilateral commitment to neoliberalism across the party aisles that leads one to hear many progressives invoke this imprecise mantra that there is, functionally, “no difference between the two parties.”

But for us to relegate neoliberalism to being solely an economic system would be to underestimate its scope and profundity as both a political and cultural project in the modern day. It has evolved from it’s early economic framing into an all-encompassing ideological doctrine, an avenue of social engineering, which, as Professor Graham Harrison of the University of Sheffield puts it, “universalizes free-market social relations totally.” In other words, neoliberalism takes the principles of the free market and applies them universally to other non-economic sectors of society. As a result, every field of activity is seen through the lens of a market, human beings become reduced to market actors and nothing more, and every aspect of our lives becomes articulated through market terms and techniques.

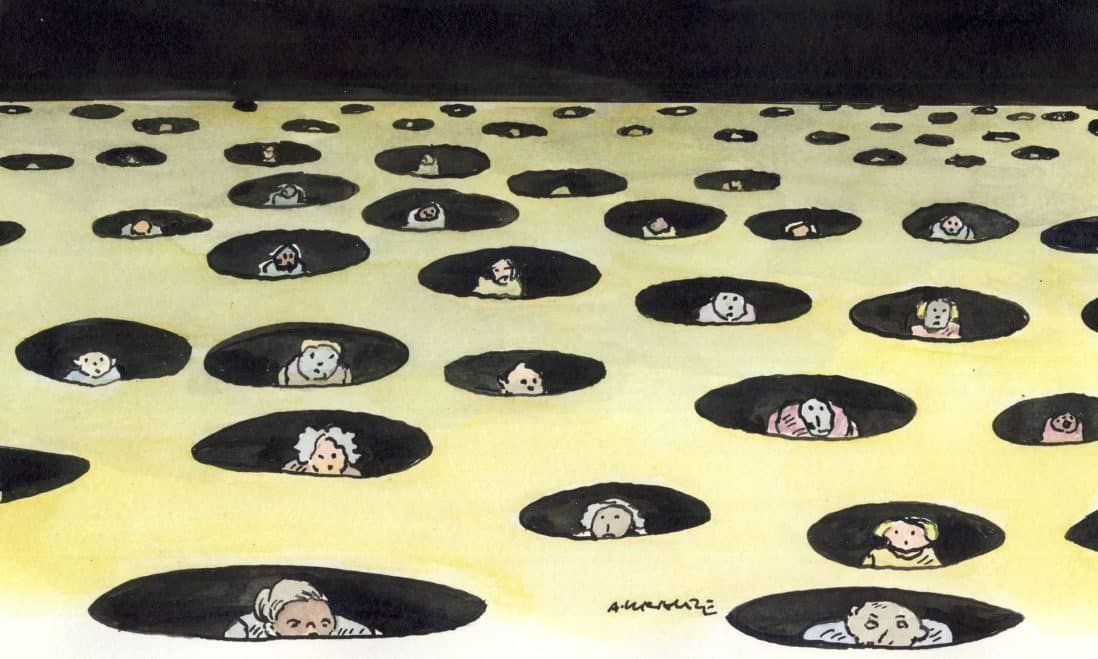

It is for this reason that in today’s America the only solutions that are politically palatable are the ones that the ‘competition’ of the market will provide, even if these solutions frequently do nothing to actually fix the problem. For instance, one might consider the way our society views the implementation of spikes and hostile architecture in front of private businesses to repel beggars as a “solution” to the issue of homelessness. In the realm of the private individual who owns the business, this solution is the cheapest one and will incur them the least cost, so even if it does nothing to solve the issue, this is the solution that the market proffers. And therein lies the problem: this transfer of power from the public to the private sphere has been going on for so long that we have effectively invoked a complete disintegration of societal cooperation to solve the issues we face. Using public funds to aid homeless people would simultaneously solve the base problem and aid these business owners who wouldn’t have to spend their private funds on hostile architecture any longer; but the short-sightedness of a society which deifies private interest prohibits such utilitarianism. As noted neoliberal Margaret Thatcher once put it in a painfully on-the-nose assessment, “There is no society… only individuals.”

The effects of over forty years of this neoliberal doctrine can be plainly seen by taking a look around at the current state of America. True to history, America has faced a sharp incline of income inequality ever since the 1980s (ever since these neoliberal policies were instituted), with income concentration in the top 1 percent and 0.1 percent having reached the highest levels they’ve been since the Gilded Age. Further, the top 1 percent of our country’s real wages are the highest they’ve been since 1979 — having grown 157 percent — whilst the median real wage, according to a Pew Research Study, has barely budged in decades. Even more precarious, before COVID, a staggering 40 percent of Americans were one missed paycheck away from poverty — a statistic which becomes incredibly daunting when one considers the rising permanent job losses incurred by the pandemic.

Moreover, the fable of the American Dream has been rendered defunct. According to a study done by the National Academy of Sciences, less than half of men and women born since the 1980s have been able to achieve upward occupational mobility, compared to the staggering two thirds of those born in the 1940s who were able to do so. It should be noted that those born in the 1980s were born into the neoliberal economy, whilst those born in the 1940s were born into the Keynesian economy; hence, why this myth of class mobility and ‘bootstrapping’ is so prevalent amongst the Baby Boomer generation.

The repercussions of this unequal economy have already manifested itself in our politics; Donald Trump’s rise to power, in large part, can be attributed to it. Voters had become disillusioned with a system that was clearly not working — they wanted to ‘burn the system down’, and Trump represented the perfect opportunity for them to do so. But further than just being a supposed anti-establishment figure, there is another key component which rendered Trump perfectly suited to take advantage of the decay of the current moment: his racist and xenophobic rhetoric. Disenfranchised and left behind, the country’s workers were looking for solutions and explanations, and in the absence of any profound alternatives, they found and consequently gravitated towards Trump’s bigoted simplification. Look not to the rich and powerful who fetter you all under the same chains, Trump says, but blame the immigrant, for it is he who is responsible for your economic woes.

It behooves the Biden campaign and its supporters, to recognize this. In 2016, the Democratic Party ran Hillary Clinton’s campaign which doubled down on neoliberalist policy (with the added caveat of a few aesthetic concessions to the left which were really only concessions in name) — in effect, the Democrats thought they could win by running on a ‘business-as-usual’ platform. It was this which was at stake when Hillary Clinton responded to Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ slogans by saying that “America [had] never stopped being great,”; it would seem that, for all of Trump’s xenophobic and prejudiced rhetoric, he was the only candidate to tell the truth, to acknowledge that there indeed was something wrong with the state of America. The Democrats must not make this mistake again; they must provide real, profound alternatives to American citizens, for if they do not, Trump’s bigotry and sectarianism will hold terrible sway over the general electorate.

Therefore, the path that the Biden campaign should take in regards to the dilemma we mentioned in the beginning of this article is quite clear. The middle in America is collapsing, brought about by the death of neoliberalism — to try to skew your platform to this quickly disappearing middle is a fool’s errand. Biden must endorse real, structural change which will positively impact the lives of those who have been disaffected by the ravages of neoliberalism; waffling over half-measures simply won’t do. Perhaps looking to a candidate who has proudly told rich donors that “nothing will fundamentally change” under his presidency to recognize this is wishful thinking; but nevertheless, for the sake of our country, and more importantly for the sake of all those who reside within it, we must hope that he will.

Featured Image Source: Illustration by Andrzej Krauze (The Guardian, October 12, 2016)

Comments are closed.