“The 9 most terrifying words in the English language,” Ronald Reagan once quipped, “are ‘I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.’” In the three decades following President Reagan’s famous one-liner, this way of thinking — a stalwart commitment to free markets and free trade — has come to dominate the Republican Party. In 2016, however, the election of President Donald Trump upended the existing political order, and with it, conservative economic orthodoxy. In the past four years, the definition of Trumpism has been a constant source of debate.

Much of this is because President Trump has no ideologically consistent framework, instead being driven by his re-election polls and a fierce urge to reverse the policies of his predecessor. Thus, while candidate Trump rose to power with a populist message — at varying times calling for increased taxes on the wealthy, criticizing NAFTA, and supporting raising the minimum wage — President Trump, with the notable exceptions of tariffs and stimulus checks, has governed as a strict adherent to the trickle-down economics of Ronald Reagan: signing a pure supply-side tax cut, pushing a healthcare bill written entirely by business interests, and crippling the administrative state. And yet, in continuing to talk about issues like the closure of manufacturing plants, the president has maintained his populist rhetoric.

Indeed, unlike many members of his own party, the president understands that the core economic message of the GOP for the past few decades has been decidedly unpopular. Recognizing the political advantage that comes with presenting themselves as supporters of the middle class, a rising populist wing of the Republican Party — led by Senators like Josh Hawley and scholars like Oren Cass — has sprung up. However, though they present themselves as allies of organized labor and opponents of corporations, the policies they push render their rhetoric toothless. This populist wing of the GOP is no friend of the middle class.

The Players

The most vocal of this “new” brand of conservatives has been Senator Josh Hawley, a 40-year-old former Attorney General of Missouri. In his 2 years in Congress, Senator Hawley has been a frequent antagonist of both Big Tech and China, deriding the former’s “exploitative and addictive business practices” and the latter’s imperialism. Behind the bluster and bravado, however, lies a much more complex reality. Mr. Hawley has done some genuinely out-of-the-box thinking on these two issues — writing legislation that would allow users to opt out of sharing their data and arguing that the US should pull out of the WTO, respectively — but beyond that, there’s little of substance. Mr. Hawley claims to support unions but has endorsed right-to-work legislation in his home state; he states that he wants to help low-income workers but has opposed any effort to raise the minimum wage; he purports to be a watchful regulator of big business but has taken millions of dollars from the Koch Brothers.

Crucial to understanding Senator Hawley is that his staunch cultural conservatism informs his economic views. This puts him fundamentally at odds with progressives; though both describe our growing economic inequality as a major problem, they link it to two very different causes. In the World Inequality Report in 2018, the progressive economist Thomas Piketty described our economic divide as driven by 1) “massive education inequality” and 2) a “tax system that grew less progressive.” In sharp contrast, during an interview with the Washington Post in 2019, Mr. Hawley ascribed America’s economic inequality to “the rise of an individualist culture that devalues traditional Christian morality.” The irony of Senator Hawley’s positions is that the policies he supports — such as tax cuts for the wealthy and overturning Obamacare — only serve to reinforce the individualist culture he decries. This should come as no surprise: since the days of the New Deal, the conservative movement has sought to cut government to the bone. With few exceptions, Republican populists share in this vision. Unsurprisingly, Senator Hawley has lent unwavering support to President Trump. Though some of this may simply be out of electoral necessity, his politics are extraordinarily Trumpian in nature: claiming to support one vision while actively doing the opposite.

Although elected officials are subject to political winds, writers, economists and scholars largely aren’t; as a result, they’re somewhat “freer” in questioning existing Republican orthodoxy. In the past few years, Oren Cass, Mitt Romney’s former Director of Public Policy in his 2012 bid for the presidency, has re-styled himself as the anchor of this new kind of conservatism. To his credit, he has gone further than Senators Hawley and Cotton. In his 2018 book, The Once and Future Worker, Mr. Cass outlines a policy vision that is in many ways unique amongst conservatives — namely, supporting the government using industrial policy to create more manufacturing jobs. By arguing that free markets don’t always work, Mr. Cass offers a refreshing take within conservative circles. Yet, beyond this, Mr. Cass’s policy prescriptions begin to wilt. As Columbia economics professor Suresh Naidu noted in the Boston Review this year, Cass opposes important policies like the ability of unions to compel dues and government intervention through the National Labor Relations Act. This illustrates a key difference between liberal and conservative economic populism: although those like Mr. Cass question laissez-faire occasionally, they don’t believe, as progressives do, in a redistribution of power from capital to labor, from the 1 percent to the 99 percent, from the CEO to the employee. In this way, Oren Cass resembles Josh Hawley: both demonstrate that conservatism’s deep skepticism of government stops the movement from enacting robust change.

Effects on Public Policy

In 2019, Senator Hawley outlined his history of where America went wrong. Rife with mischaracterizations, his speech reserved much of its criticism for a so-called “cosmopolitan elite” who “regard our inherited traditions as oppressive and our shared institutions — like family and neighborhood and church — as backwards.” Here, Hawley takes issue with “woke capital,” the popular idea in conservative circles that corporations too often push culturally liberal values. To be sure, while big companies often do cynically exploit social movements for good PR and better profits, Senator Hawley uses this as a red herring. As the journalist Gilad Edelman puts it, “to a Bernie Sanders or an Elizabeth Warren, the problem with woke capital is the capital. To a Josh Hawley, it’s the wokeness.” And that makes all the difference. Conservative populists ignore the structural political and economic forces at play in favor of a short-sighted critique of cultural liberalism.

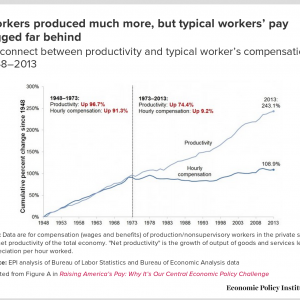

The difference this makes at the policymaking level is huge. In the past 40 years, wages have fallen far behind productivity. As writer Eric Levitz explains in New York Magazine, worker productivity rose 96.7 percent from 1948 to 1973 and hourly compensation rose 91.3 percent. From 1973 to 2013, however, productivity rose 74.4 percent, while hourly compensation rose just 9.2 percent. Similarly, the drastic increase in prices of education, housing and healthcare have far outpaced the meager increase in income. And, all of this comes at a time when income inequality in America has grown astronomically.

Behind all of the lofty talk about the greedy elites and the woke CEOs, conservative populism has little to offer in the way of solving these problems. Mr. Cass is a frequent critic of Obamacare and Medicaid, and Senator Hawley has fallen behind President Trump’s thinly veiled racist push to “protect our suburbs” without offering any meaningful vision. It would perhaps be irrational to expect conservatives to support Bernie Sanders’s Medicare-for-All bill or Elizabeth Warren’s affordable housing plan, but it is reasonable to expect some plausible ideas to restore the American Dream. They have almost none. In the face of stagnant wage growth, a housing affordability crisis and millions of people without healthcare, Senator Hawley is asking a lot out of Americans if he expects us to believe that “the devaluing of traditional Christian morality” is the primary driver of America’s economic divide.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Given these trends, it’s unlikely that outside of a few areas — most notably trade and industrial policy — the Republican Party will look much different in the next four years than it has in the past four, or, for that matter, forty. Two of the most popular Republicans, Nikki Haley and Tim Scott, are rigid Reaganites. Don Jr. and Ivanka Trump are among the top five prospective candidates for the 2024 primaries, according to a 2020 Axios poll. A recent Politico piece describes conservative rumblings for a potential Tucker Carlson presidential bid. In light of this and the populist conservatives’ lack of substance, the Republican Party will likely continue along the same lines it currently has. However, populist rhetoric and white identity politics have already proven to be a winning combination, and the thought of a candidate without the president’s baggage deploying this potent formula should be alarming to Democrats.

Looking back, President Trump’s popular 2016 message, “drain the swamp,” has been reversed 180 degrees. Mr. Trump’s administration is flooded with rank-and-file Republicans, and his four chiefs of staff have been the chairman of the Republican National Commitee, a Marine General, and two former GOP Congressman — hardly bastions of populism. Moreover, even the top members of the administration who weren’t “Washington Insiders,” such as Steve Bannon and Stephen Miller, have prevented Mr. Trump’s popuist rhetoric from becoming a reality. The month after President Trump was inaugurated, Mr. Bannon vowed a “deconstruction of the administrative state,” the same collection of entities that is necessary to provide unemployment benefits, protect unions, and prosecute corporate greed. The conservative vision of “drowning government in the bathtub” has become a reality. And remarkably, the self-proclaimed champions of the working people — the same working people who the public sector can help most — are the ones who made it that way. This governing framework, of rhetorically criticizing corporations and supporting unions while deconstructing the administrative state, is the equivalent of fighting a war with no weapons and no ammunition. It’s also why there’s a deep tension between conservative populism and liberal populism: one seeks to radically shrink government; the other seeks to grow and wield its power.

Last year, antitrust scholar Matt Stoller remarked that “Josh Hawley has the populist lane all to himself.” While this is undoubtedly an overstatement — and does a disservice to the economic populism of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren — it speaks to the vacuum left behind by Democrats, who share some blame here too. In the 1990s, President Clinton deregulated the banking industry, cut welfare, and signed NAFTA over the objections of organized labor. In the 2000s, President Obama presided over massive corporate mergers, let a foreclosure crisis run amok, and pushed for an expansive free trade deal. If the intellectually bankrupt Republican Party is to be stopped, it will take change from mainstream Democrats as well. The populist wing of the GOP is no friend of the middle class; it’s incumbent upon Democrats to be.

Featured Image Source: Bill Greenblatt, UPI

Comments are closed.