What Underhandedly Racist Comments Sound Like and Why They Call for Self-Reflection

Although slavery was abolished in 1865, its long-lasting impact is still felt in 2020. However, the difference between 1865 and 2020 is that racism is not as blatant. Racism has diverted away from textbook imagery and is now predominantly emulated through implicit biases and projected microaggressions. Still, it is important to acknowledge the horrific textbook history of slavery and its very real impact on society today. Nevertheless, modern molds of racism still require serious societal self-reflection.

What Are Racial Microaggressions?

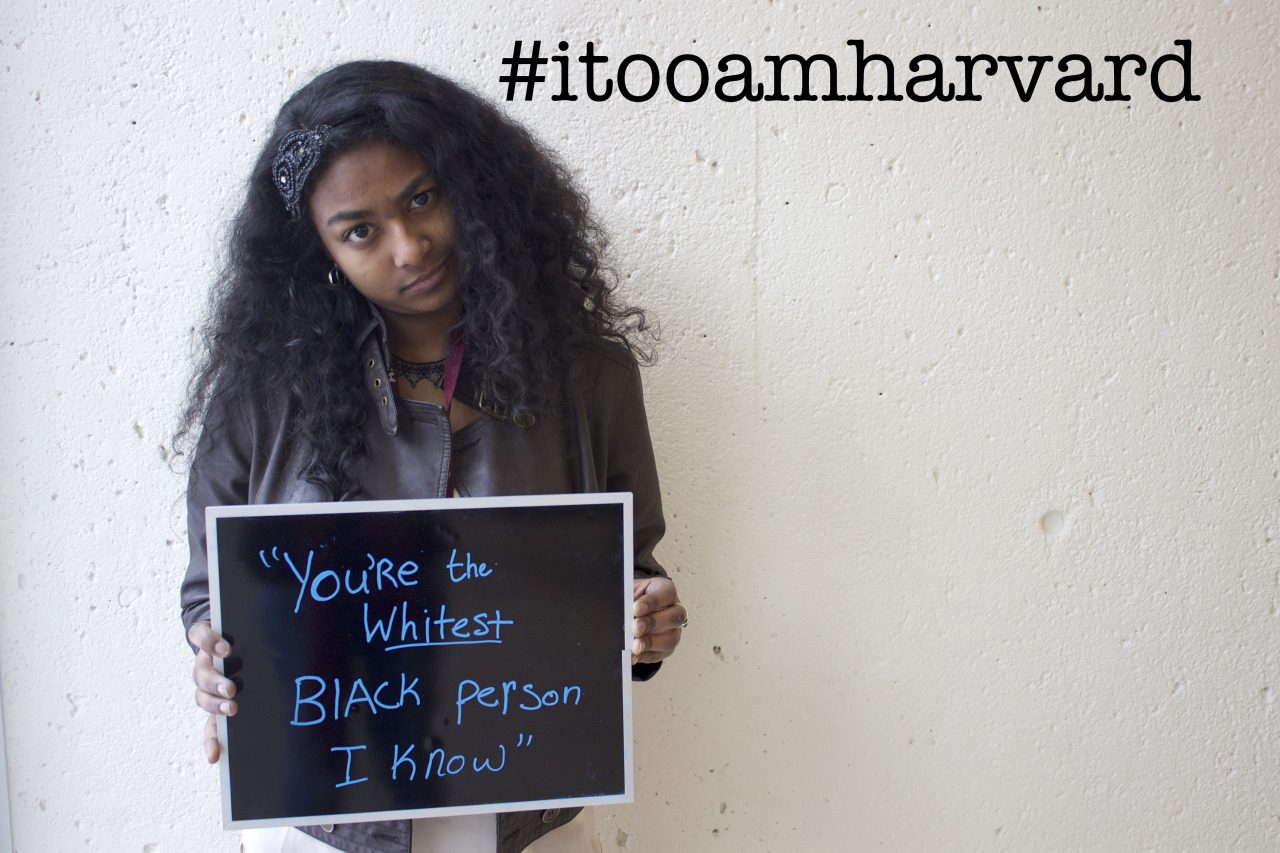

Racial microaggressions are projected racist beliefs that are often so subtle that they can go unrecognized by the speaker. Sometimes, even the victim of these projected comments may not recognize the backhanded nature of a micro-aggressive statement. For example, “you don’t sound Black” is a comment with strong racial microaggressions implied. Though the intent is questionable, the underlying root of the comment is the speaker’s internalized belief that Black people are inherently less educated and, thus, communicate poorly compared to the ‘educated’ and ‘elite’ white society.

Harvard psychiatrist Dr. Chester Pierce first studied and coined the term “microaggression” in the 1970s. He defined these microaggressions as racial putdowns that negatively impacted the health of a victim over time. Since the 1970s, several psychologists have studied the impact of racial microaggressions on the day-to-day lives, wellbeing, and health of the Black community. It has been concluded that microaggressions are present in the workplace and education system and are commonplace in conversations, behaviors and attitudes. These studies further divulge how even unintentional racial microaggressions drastically impact the physical and mental health of people of color (POC).

“All lives matter”

“Where are you actually from?”

“I’m not racist, I have a Black friend.”

“Wow, you are so articulate.”

“Is that your natural hair? Do you want to brush it before we give this presentation?”

“You don’t sound Black.”

“You don’t have to worry about getting into college, you’re Black.”

The Deeper Meaning Behind Microaggressive Comments

Although not transparently seen as racist beliefs, the opaque nature of these backhanded comments come across as tone-deaf, offensive, and privileged. “All lives matter” emerged as a movement to counter the Black Lives Matter revolution. However, preaching “all lives matter” directly challenges and mutes the prevalence of racism that is now predominantly whispered in our societies. Asking a Black individual “where are you actually from?” reflects the persistent perspective that America is still considered a white person’s land in 2020. Using “I have a Black friend” as some sort of evidence for not being racist is a toothless defense mechanism and invalid rebuttal that reflects implicit biases. Telling a Black person or any POC that they are articulate underhandedly implies that POC individuals are inferior at emoting and communicating.

These may not seem like racist comments on the surface-level, but the backhanded nature of these comments lays between the lines. Any backhanded comment, such as praising a heavier woman for her confidence, is distasteful in nature. Yet, this reality is difficult to recognize for many speakers who, when confronted about underlying racism in microaggressive comments, often tend to react defensively.

Realizing Individual Implicit Biases

A common response for someone who is confronted for projecting their implicit biases through racial microaggressions is to become defensive. These defense mechanisms, coined “White fragility”, prevent white Americans from addressing their implicit biases. The institutionalized racism in America is one that white individuals have benefitted from, and implicit biases are an indirect mechanism in which white America seeks to remain sheltered and protected with opportunities. Speaking on the matter of defensiveness, clinical psychologist Dr. Taslim Alani-Verjee explained to Huffington Post, “no one wants to acknowledge that they’re racist.” Furthering that, “we reject the person’s claim, usually bring up all of the reasons why we’re not racist in the process. And we end up potentially silencing or further marginalizing the individual who is bringing it up.”

Furthermore, racial microaggressions can lead to adverse impacts on an individual’s mental health that is correlated with trauma, depression and lower self-esteem. In kindergarten, we are taught the golden rule is to treat others how we want to be treated. Yet, we as an overall society are unwilling to acknowledge how our implicit biases negatively impact others. As we grew up, we lost sight of the golden rule. Without self reflection, Black individuals will continue to be exposed to the psychological and physical stress of implicit racism.

Still, the stereotype remains that so long as a person does not engage in apparent discrimination (i.e. in the form of slavery), they are not racist. However, the issue persists that individuals neglect how their personal biases and prejudices are being relayed in the form of racial microaggressions. When studying 1.8 million white participants taking an implicit bias test, Lehigh University professor Dominic Packer suggested that implicit biases were more common in locations where the abolition of slavery in America threatened white interests. The results of this study provides support for how implicit biases and resulting discriminatory nature are the root of institutions and society today. However, Packer’s research ultimately provided a beacon of hope for addressing the implicit biases that ultimately control institutionalized racism. He explained, “if we understand the factors that shape implicit responses in the present, perhaps progress in addressing intergroup disparities will begin to catch up to our consciously felt egalitarian principles.”

A Desperate Need for Societal Self-Reflection

To address how rooted racism is still impacting the Black community, change needs to come from self-reflection at the individual level. Packer’s research provided a sense of hope that racism can be addressed and de-rooted. Nevertheless, change has to begin with the self-initiative of acknowledging how racism is still prevalent in our modern society and was not eliminated with the abolition of slavery. Furthermore, eliminating the roots of racism calls on the individual to self reflect. This introspective thinking should be done consciously with the intent of keeping an open mind, being willing to acknowledge implicit biases, and accepting responsibility to learn from any past mistakes. Furthermore, the individual must educate themselves on the very real discrimination prevalent in America through informing themselves on the BIPOC perspective, whether that be reading books and articles written by Black authors, watching movies or films directed by Black creators, or just having conversations with an individual who may have experienced being the target of racial microaggressions.

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement is not a new revolution of 2020. The movement emerged in 2013 after Trayvon Martin’s murderer was acquitted. It regained traction in 2016 on Twitter and has now resurfaced in the media. Still, the ideology behind the BLM movement is to combat the racist institutions that the United States was founded on 244 years ago. These racist beliefs still remain in our nation due to the countless individuals who perpetuate racist and discriminatory mindsets, whether intentionally or not, by their own predetermined biases of the Black and greater POC community. Still, microaggressions go beyond race and can be projected as sexist, xenophobic, homophobic or any other form of discrimination against a community.

The long-term elimination of any of these discriminatory ideologies must begin with the individual self. Underhanded comments are a reflection of the speaker’s belief system, and the only way to create real change is to self reflect, to openly acknowledge mistakes, and to be willing to change one’s mindset. In a country that prides itself on diversity, the traditional white America has continuously benefitted from silencing BIPOC individuals and their narratives through opportunities, mobility and profits; acknowledging this reality is the first step to change. Overarching changes, such as the abolition of blatantly discriminatory laws and slavery, have been made in the U.S., but rooted racism has yet to be extinguished. To live in a world with genuine equality, fairness, and justice, people should not be afraid of change – changing their minds, changing their opinions, changing their country’s social institutions. This change begins with the individual self.

Featured image: “I, Too, Am Harvard” Campaign

Comments are closed.