Psychedelic drugs are often associated with deadbeats, dropouts and eccentric musicians. Using them as medicine seems like something straight out a hippie handbook, but it is a concept that has been gaining traction among medical researchers in recent years. We are currently experiencing a renaissance of psychedelic research, exploring the potential applications of criminalized psychedelic drugs — also known as entheogens — as breakthrough treatments for an array of ailments including depression, anxiety, PTSD and addiction. As a growing body of research points to their benefits, it is important to know why these drugs are feared by many and what the science is about their current applicability. In particular, psilocybin (the compound in “magic mushrooms” that makes you trip) is demonstrating legitimate clinical applicability for the aforementioned conditions. People ought to understand what this substance is, how it works in the brain and where the research surrounding it is at. Only through de-stigmatization can good drug policy be implemented, allowing scientists to continue to explore potential clinical benefits of psilocybin and similar compounds that may provide alleviation for the suffering of many people. Science, not stigma, should drive the conversation forward.

Ancient medicine

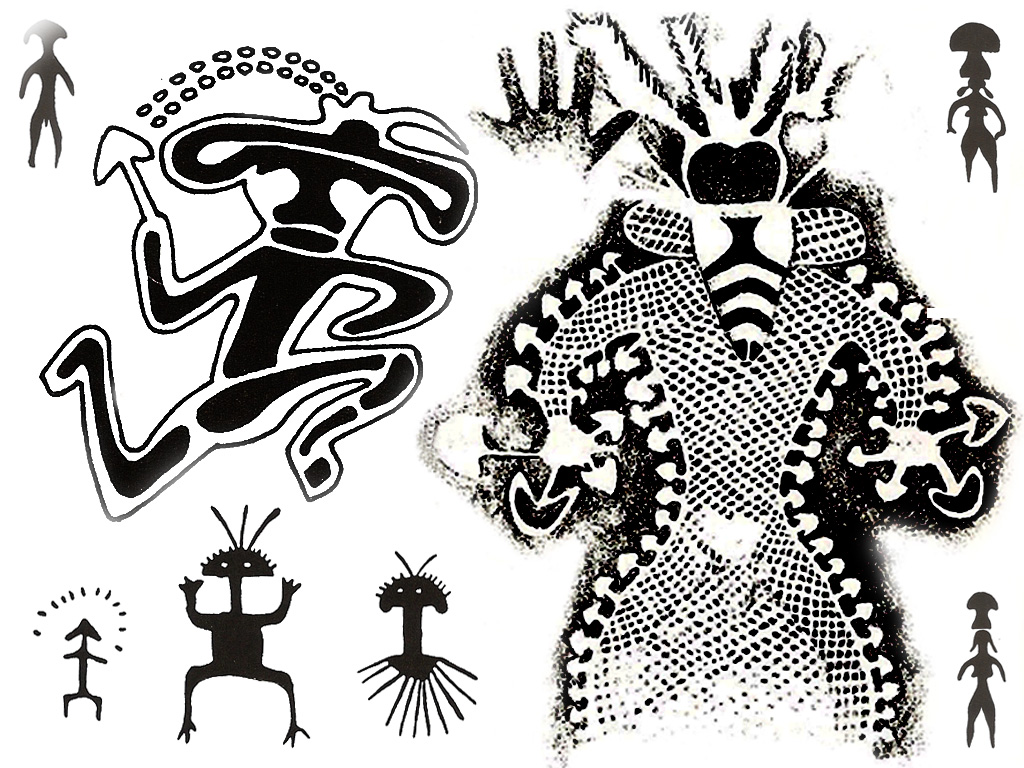

While modern western medicine is just beginning to categorize the benefits of entheogenic substances, humans around the world have used them in healing and spiritual rituals for thousands of years. Ten-thousand year old cave art in the Sahara desert depicts a bizarre mushroom-covered bee-faced shaman. Five-thousand year old Sanskrit texts contain mentions of a godly drink called soma, thought to be derived from the psychotropic fly-agaric mushroom. Siberian tribes have been documented using psychotropic mushrooms for spiritual and medicinal purposes, and art from the region suggests this practice is thousands of years old. The Aztecs consumed a Psilocybe mushroom they called teonanacatl, flesh of the gods, for healing and religious ceremonies. The ancient Greeks are suspected of consuming ergot, a fungus with LSD-like effects, during their Eleusinian Mystery Rites. It has even been hypothesized that early Christians spiked their wine with hallucinogenic compounds as an outgrowth of earlier Greco-Mediterranean usage of entheogens. Western society largely forgot about these substances in the years following European colonialism and the industrialization of society. It was not until recently that psychedelic compounds were rediscovered by the Western world.

Magic mushrooms and the US

In 1955, a JP Morgan banker by the name of Robert Gordon Wasson traveled to the remote southern Mexican village of Huautla de Jiménez to participate in an ancient Mazatec ritual led by the shaman María Sabina. Wasson and his party ingested so-called divine mushrooms, scientifically classified as Psilocybe mexicana, which were meant to open their minds to God, though typically these mushrooms were used in rituals on those who were sick. Wasson described his experience in a 1957 issue of Life magazine:

I felt that I was now seeing plain, whereas ordinary vision gives us an imperfect view; I was seeing the archetypes, the Platonic ideas, that underlie the imperfect images of everyday life… the effect of the mushrooms is to bring about a fission of the spirit, a split in the person, a kind of schizophrenia, with the rational side continuing to reason and to observe the sensations that the other side is enjoying. The mind is attached as by an elastic cord to the vagrant senses.

Wasson’s exploits kicked off the reintroduction of psychedelic mushrooms to western society. After multiple experiences with Sabina (and unintended tragic consequences for the shaman), Wasson brought dried mushrooms and his knowledge to the United States, where he became an advocate for psychedelic use. He also sent samples of the Psilocybe mexicana mushrooms to Swiss chemist and father of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) Albert Hofmann, who was able to isolate the psychoactive compound he named psilocybin from the mushrooms.

While the CIA sought to weaponize psychedelics in classified, sinister research programs, medical research into psychedelic compounds was also underway, with researchers and psychotherapists exploring the potential therapeutic benefits of psilocybin, LSD and other psychotropic chemicals. Through the 1950s and 1960s, over a thousand research papers on the subject were published, and more than 40,000 subjects were given psychedelics to help scientists understand how these compounds might help people with conditions like depression, alcoholism and end of life anxiety. The Good Friday Experiment in 1962 suggested that psilocybin could induce authentic religious experiences that still influenced participants after a 25 year follow up. These preliminary results warranted further exploration; psychotropic compounds clearly showed an ability to influence human cognition and represented untapped potential for therapeutic benefits.

The burgeoning field of clinical psychedelic research ground to a screeching halt as the 1960s bled into the 1970s and the government started cracking down on the pro-drug counterculture movement. The overuse of mind-altering substances by young people in America overshadowed the research that was coming out, and politicians sought to purge such substances from society. The epic failure of the War on Drugs policy placed psilocybin and LSD in the Schedule I category — the worst classification a drug can receive, where they have remained to this day — meaning the DEA claims it has “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Less harmful (according to the DEA) are fentanyl and meth, Schedule II drugs. At the same time, the government waged a propaganda campaign that demonized psychedelics and marijuana as insanity-inducing substances that would ruin the minds of the youth. This strategy was mimicked by other world governments, and psychedelics were driven from legal research while becoming reviled in the public image for some time.

In recent decades, public opinion has shifted towards general acceptance of once reviled drugs. Evidence has shown that mushrooms and LSD are the least dangerous drugs taken recreationally, lacking major addictive potential or physiological damages. Coinciding with this shift in public sentiment has been a renewed interest in exploring possible therapeutic benefits and, ever so slowly, some relaxing of government policies.

How does psilocybin work?

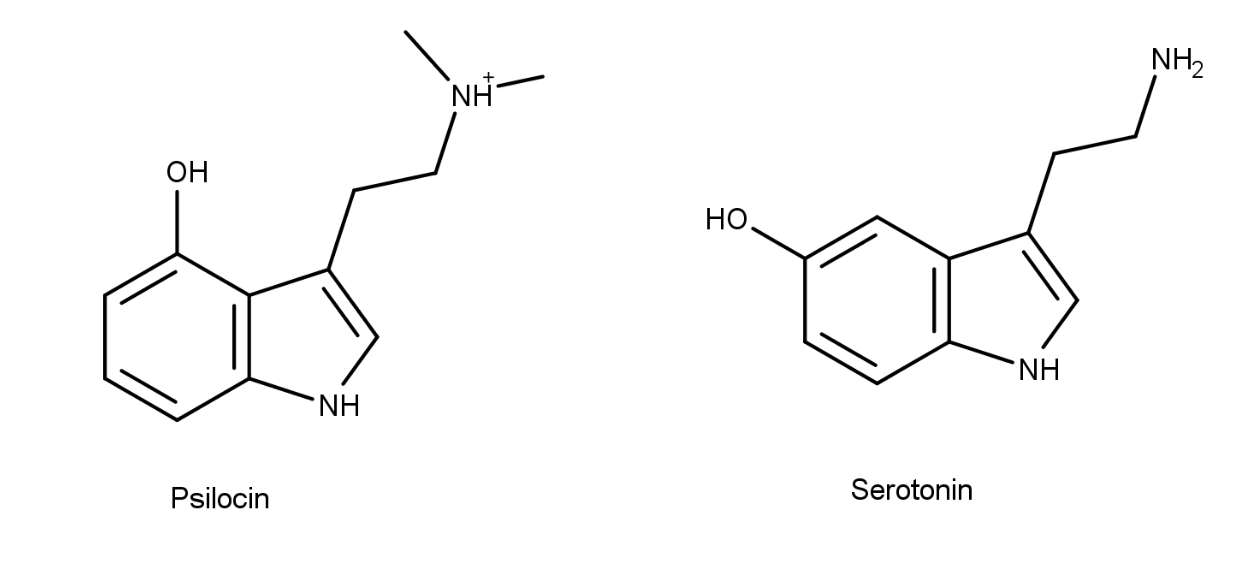

Let’s back up for a second. What exactly is psilocybin, what does it do and why does it exist? Over 200 species of mushrooms contain psilocybin, a chemical compound that very closely resembles the neurotransmitter serotonin, one of our brain’s natural chemicals. While psilocybin has a potent effect on humans, it turns out we are not its intended target: studies show that psilocybin kills insects’ appetites, stopping them from eating the mushrooms and their food sources.

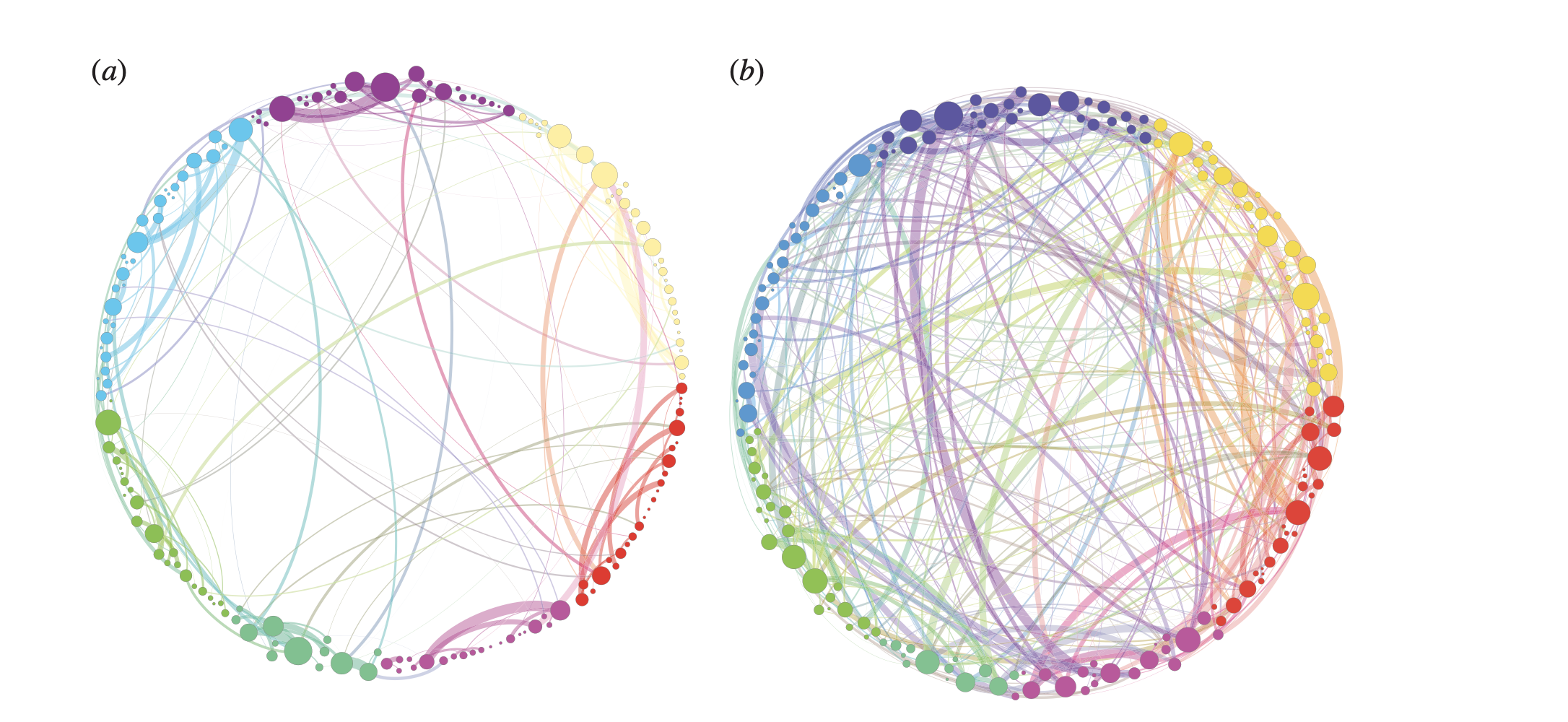

Psilocybin works precisely because it resembles serotonin. Once ingested, psilocybin is converted into psilocin, its active form that can interact with the brain by binding to serotonin receptors, which are designed to receive serotonin neurotransmitters, but also fit with the lookalike psilocin. Once psilocin binds to the brain, it triggers a superbly named process called neuronal avalanching whereby bursts of activity in the brain cause a “domino-effect” of changes in how the brain operates: increased activity in the visual cortex (hallucinations, vivid colors), decreased activity in the default mode network (an effect also achievable by meditation, which leads to a loss of ego, or sense of self), decreased activity in the amygdala (a region involved in processing fear and anxiety) and heightened communication across brain networks (leading to new thought pathways, greater introspection, epiphanies, and for some individuals a sensory overlap called synaesthesia — seeing sounds, hearing colors). There are numerous other physical and mental effects associated with psilocybin use including pupil dilation, time distortion, euphoria, giggling, relaxation, paranoia, anxiety, increased heart rate and loss of appetite. However, the main scientifically intriguing outcomes are those relating to brain activity.

Taking a look at some of the effects of psilocybin that have already been laid out, it is not hard to speculate that it could have effects on mental health issues like depression, addiction and PTSD. But speculation is not all we have; the current resurgence in research is showing that there is empirical evidence to support the therapeutic effects of psilocybin for a range of harmful mental health outcomes.

To begin, it interacts with serotonin receptors, the same parts of the brain that are targeted by the common antidepressants called SSRIs and play a critical role in the complex neurological phenomenon known as major depressive disorder. Psilocybin also reduces amygdala activity, which has been correlated with reduced depressive symptoms in treatment-resistant patients. Research has also shown that psilocybin can “reset” the activity of key brain circuits centrally involved in depression. While it is important to note that research is still in the early stages and it will likely take several years of trials to be considered legitimate, early clinical trials continue to show promise. A study by the Beckley Foundation gave psilocybin to 20 patients who had suffered from treatment-resistant depression for an average of 18 years and recorded improvements in all of them after one- and five-week intervals, with positive results still visible during three- and six-month follow up exams. Reductions in depressive symptoms were positively correlated with the quality of the acute psychedelic experiences of the patients. The institute summarizes some patient responses to the novel treatment:

Many of these patients said that they attributed the effectiveness of the treatment to “a greater willingness to accept all emotions”. Many went so far as to say that they felt previous depression treatments had worked to “reinforce emotional avoidance and disconnection”. The psilocybin experience itself, by contrast, had precipitated an emotional “confrontation”: a challenging return to old traumas that had led to “emotional breakthrough and resolution”. The therapeutic process that was by no means easy or pleasant was nevertheless felt to have been pivotal to achieving a therapeutic transformation.

Other small scale studies have yielded similar promising results, to the point where the FDA has actually fast-tracked the development of two psilocybin based antidepressants in recent years, granting them “Breakthrough Therapy” designations. This means that their development is expedited because they have a real possibility of providing “substantial improvement over available therapy”.

Depression is not the only mental illness that psilocybin is being tested as a potential remedy for. Studies showing psilocybin erasing conditioned fear responses in mice have prompted novel clinical trials for psilocybin as a treatment for PTSD in veterans. Empirical evidence shows how psilocybin produces “substantial and sustained” decreases in anxiety and depression for patients with life-threatening cancer. The rewiring potential of the compound has also shown applicability for treating addiction.

What’s more, anecdotal evidence for the healing potential of psychedelics abounds. While clinical studies are more credible, thousands of individual reports of purported benefits likely speaks to some level of inherent truth that science can parse out or cast aside if found to be false. But so far, the evidence is pointing to some tangible therapeutic upsides of psilocybin as a treatment for mental ailments.

Beyond medicine

Entheogens like psilocybin are also potential avenues to explore some of the more nebulous aspects of human nature. Beyond their clinical applications, these mind-expanding compounds offer opportunities to explore mysteries regarding two of the most central aspects of human existence that science does not fully comprehend: the brain and consciousness. Despite the fact that both of these things are inherencies in human life, there is so much we do not know about them. As one neuroscientist put it, consciousness is a “controlled hallucination” created by your brain, and when our hallucinations agree with each other, we call it reality. In studying psilocybin, a group of scientists accidentally proved that a person’s sense of self is an illusion created by the mind which can be temporarily lifted by turning off the default mode network. They found that people experienced a reality where they were not the protagonist and were exposed to a novel form of consciousness that allowed for new revelations. While this is being explored for its benefits for treating depression, it also begs greater questions about what consciousness is and how real a sense of self truly is if it can be switched off.

What are the takeaways?

Psilocybin is a fascinating compound whose benefits are starting to be explored in earnest with breakthrough potential. Without a doubt, it deserves further study. This could be facilitated by the government if it allowed researchers to access more of these compounds, namely by removing them from the Schedule I classification they have been unfairly relegated to. While the early research is certainly promising, this in no way represents a silver bullet. Psilocybin will certainly not cure everyone. The early benefits may turn out to have been over exaggerated. But if there is any marginal benefit to the development of psilocybin based therapies, which scientists and the FDA believe there is, then it is worth it for the thousands of people who could stand to benefit from novel treatments to serious conditions like depression, anxiety, PTSD and addiction. As society continues to grapple with mental health issues, new methods for combating debilitating mental illnesses are always welcome. In this arena, psychedelic compounds may offer new hope for many and certainly deserve research, funding and close attention in the coming years.

Featured Image Source: Nova Recovery Center

Comments are closed.