Israeli-Arab diplomatic breakthroughs mean little for West Bank residents

August 2020 —A crowd of hundreds marches towards the outskirts of the Palestinian town of Turmus’ayya. They are headed in the direction of an Israeli military checkpoint, located just 500 meters from the edge of their town. The goal of the Palestinian marchers: to pray on their farmland.

The Israeli military perimeter is in place to protect new settlement construction about two miles from the town, according to Turmus’ayyan Mayor Said Talib. The construction is taking place on farmland owned by Palestinian residents of Turmus’ayya, and the military checkpoint is meant to protect the construction by keeping them away.

The crowd advances towards the checkpoint despite warnings to turn back. The people hope to cross the line and reach their farmland to protest the construction through prayer. Instead, they are fired upon with rubber bullets and tear gas. The marchers are forced to turn back. Six International Red Cross workers were among those struck and injured by rubber bullets, says Talib.

This story was recounted to me over the phone by Mayor Talib, about four days after the incident reportedly took place. It has not been widely reported, though there was some Palestinian coverage.

Scenes like this are not new for the West Bank. The territory, which lies between Jordan and Israel, came under Israeli military occupation from Jordan after the 1967 Six Days War. It had previously been part of the Ottoman Empire and then the British Mandate in Palestine before falling under Jordanian control during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Since the 1967 occupation, the Israeli government has supported the construction of Israeli towns and cities in parts of the West Bank. This population transfer is considered illegal by most of the international community, but the Israeli government disputes this. It argues that, because Jordan renounced its claim to the West Bank, the land has no “legal sovereign” and can therefore be occupied. The Palestinians have never governed their own state despite living on the land for centuries.

Israel had been attacked twice through the West Bank before 1967, so the first Israeli settlements in the West Bank were justified on security grounds. There was subsequently a religious movement to further Jewish settlement of the land, which is culturally important to Jews and is referred to as Judea and Samaria in the Hebrew Bible.

Today, the settlements are fairly integrated into normal Israeli civilian life. “Most of the settlers are not there for ideological reasons,” says Professor Ron Hassner, Chair of Israel Studies at UC Berkeley. “Most people simply live in settlements because the real estate is cheap, it’s an easy commute to the center of Israel, it’s safe [and] it’s less dense.”

The construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank has been a major point of conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, who have for decades aspired to end the occupation and create their own state. The occupation and settlements also remain divisive issues within Israeli domestic politics. The Israeli and Palestinian leadership have not made serious strides towards a resolution in two decades.

A Fragile Peace

Tensions simmered in the West Bank until 1987, when the Palestinian population spontaneously revolted against the Israeli occupation in what became known as the First Intifada. The six years of violence that followed, as well as international criticism of Israel’s response, pushed the leadership of both sides to negotiate.

In 1993, Israeli and Palestinian leadership, with the help of US President Bill Clinton, signed the Oslo Accords. The deal was the first step towards a gradual transition from Israeli occupation to independent Palestinian government in the West Bank.

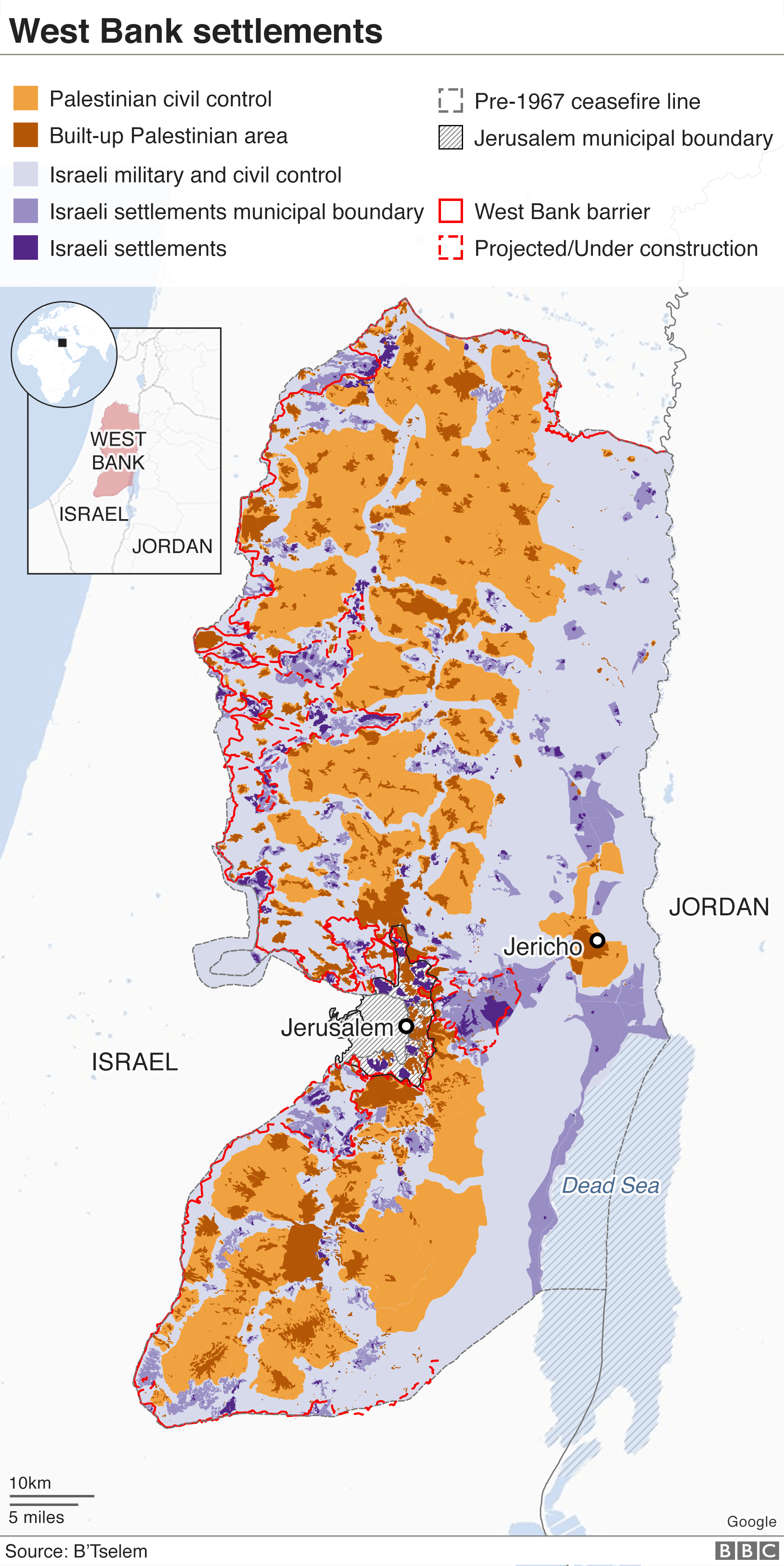

The Oslo Accords divided the West Bank into three areas: Area A, Area B, and Area C.

Area A, home to all major Palestinian population centers in the West Bank, is governed by the Palestinian Authority (PA) but the Israeli military retains the right to intervene for security purposes. Area B, comprised of more rural Palestinian areas, has some PA administration while Israel is responsible for security. Area C, mainly comprised of Israeli settlements in the West Bank, is administered by the Israeli military with help from civilian councils.

The Oslo Accords were meant to be a five-year transition plan, but relations between the Israeli and Palestinian leadership broke down in the years afterwards. Israeli faith in the peace process was further weakened by the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin at the hands of a Jewish nationalist and by the failure of negotiations in 2000.

Tensions erupted again in the far more violent Second Intifada in 2000, which was marked by a series of Palestinian suicide bombings in Israel and extensive Israeli military operations across the West Bank. Violence in the West Bank has calmed down in recent years. But nearly thirty years after Oslo, little progress has been made towards sustainable peace or independent Palestinian government in the West Bank.

Life in an Israeli Settlement: In Pursuit of Normalcy

NEVE TZUF — Despite the challenges of living on disputed land, Israeli communities in the West Bank are prosperous.

“This is the place I want to raise my family,” says Miri Maoz-Ovadia, 33. Maoz-Ovadia was raised in the Orthodox Jewish settlement of Neve Tzuf, which was established in 1977 and today has a population of roughly 1,500 people. She continues to reside there today with her husband and three children and works as a receptionist for a regional branch of the Yesha Council, the civilian council which helps administer the settlements.

Speaking over the phone, Maoz-Ovadia described Neve Tzuf as a tight-knit, traditional, “very normal” community without a large military presence. It is located ten miles from the Green Line, which separates the West Bank from Israel. “People work all over Israel and [here] in the community,” she said. A highway system connects Israeli settlements in the West Bank to the rest of Israel, allowing residents of towns like Neve Tzuf to be integrated into Israeli society.

“We see this area as part of Israel,” said Maoz-Ovadia, who uses the biblical terms Judea and Samaria to describe the territory. “It’s always been part of Jewish history.”

Families like Maoz-Ovadia’s do accept a certain reality by living on disputed land. “Living in an area that’s full of tension can be difficult,” she says. “People who live here have the emotional strength.”

Residents of Neve Tzuf face infrastructure, water and electricity issues, including an “appalling lack of medical services,” said Maoz-Ovadia. The most striking issue facing residents of settlement communities like Neve Tzuf, however, is violence.

“My community suffered many terrorist attacks,” said Maoz-Ovadia. She described a 2017 stabbing attack which left three locals dead. The town was also victimized in a larger wave of arson attacks which claimed 18 homes in the town alone.

These incidents have contributed to a sense of suspicion and fear among some Israeli settlers towards their Palestinian neighbors, even among those who are not hateful. Maoz-Ovadia has visited Israeli Arab schools to talk with students about her life in a Jewish settlement and believes that peace is achievable. But she still expressed her belief that the Palestinians are overall more responsible for the continuing conflict. “Revenge is a commitment with the Palestinians and the Arabs,” she said. “Revenge is against Jewish law.”

There is little contact between Israeli settlers in Neve Tzuf and their Palestinian neighbors, who are just minutes away by car, said Maoz-Ovadia. But when they do encounter each other, the results can still be positive. “People are good as well,” she said, specifically mentioning Palestinian tour guides who often work in her town. “We understand that the conflict is really deep.”

Life in a Palestinian Community: In Pursuit of Justice

TURMUS’AYYA — While living under occupation, Palestinians in the West Bank have also made do with their circumstances. “Palestinians in the West Bank are relatively prosperous compared to [other] Arabs in the Middle East,” said Professor Hassner. “They’re doing pretty well in terms of average income, food supply, even in terms of COVID.”

Turmus’ayya, the small town governed by Mayor Said Talib, is actually one of the wealthiest towns in the West Bank. Much of the population of Turmus’ayya, including Mayor Talib himself, have dual American citizenship and split their time between the West Bank and the US.

This American connection has influenced the outlook of the town’s residents. “I’m proud to be American. Palestinian-American,” says Talib. “We know human rights because we have been to America.”

Despite their relative affluence, the people of Turmus’ayya are concerned about violations of their basic human rights.

According to Talib, Israelis from the nearby settlements have entered Turmus’ayya, on different occasions, to torch cars, slaughter sheep and spray paint “All Palestinians Must Die.” One of Talib’s constituents was allegedly shot, along with his family, while farming in their field. The justification: the family had strayed too close to the Israeli perimeter.

In October, shortly after my conversation with Talib, a 16-year old Turmus’ayyan boy was killed during a search-and-arrest operation conducted by the Israeli military.

The West Bank is not presently in a state of open conflict. These contemporary incidents do not begin to scratch the surface of the trauma caused by earlier, more violent periods in the conflict. But Palestinian concerns are not limited to violence. They also extend to property and travel rights. To understand this issue, it is important to understand the geography of the area.

Most of Turmus’ayya, including the entire population of about 3,000 people, is located in Area B. As previously noted, land in Area B is primarily administered by the Palestinian Authority, but Israel retains responsibility for security.

However, a significant chunk of land historically part of Turmus’ayya, about 35 percent, is actually classified as part of Area C under the Oslo Accords. This means that 35 percent of Turmus’ayyan land, mostly open space and agricultural land, is fully controlled by the Israeli military and is open to construction and settlement by Israeli civilians.

Two Israeli settlements, Shilo and Mizpe Rahel, are located within the historical town borders of Turmus’ayya in Area C. Their population numbers about 2,500, according to the Applied Research Institute of Jerusalem (ARIJ), a West Bank-based NGO funded by the European Union. Other settlements exist near the town border.

The division of Turmus’ayya between Areas B and C, an issue also experienced by other Palestinian towns, poses critical issues for residents. One of the most pressing is freedom of movement.

The Israeli military restricts travel from Areas A and B to Area C for security reasons. The combination of checkpoints, stops and detours can turn the 15-mile drive from Turmus’ayya to the city of Ramallah into a full day’s journey, said Talib. This imposes significant burdens upon Palestinian travelers.

Furthermore, these restrictions impede the ability of Palestinian Authority emergency services to reach the rural communities in Area B. The residents of Turmus’ayya are effectively isolated as PA emergency services, including police, must cross checkpoints and coordinate with the Israeli military in order to reach them. This means that it can take hours for emergency services to reach Turmus’ayya.

A related issue facing Palestinians, including Turmus’ayyans, is land and property rights. Much of the farmland in the Area C portion of Turmus’ayya is privately owned, yet access to the land is restricted by the Israeli military because it is in Area C. Mayor Talib himself personally owns farmland located in Area C. “We can’t even reach our own land,” he said.

According to Mayor Talib, he and other landowners are only allowed to access their farms twice a year, in October and April, for three days at a time. They are only allowed to collect olives from their olive trees and may not cultivate any other crops. Agriculture, particularly olive tree cultivation, is by far the largest sector of the Turmus’ayyan economy, according to the ARIJ.

Palestinian land which is close to Israeli settlements, such as Talib’s, is subject to a permit system operated by the Israeli Civil Administration (ICA). The ICA decides when land owners may visit their land, and three day visiting periods are not unusual. The ICA’s official policy, in accordance with a 2006 Israeli High Court ruling, allows Palestinians to “get every last olive from every last tree, even if that tree is in the middle of a settlement.” But there have been numerous reported violations of Palestinian crops, particularly olive trees.

In some cases, the olive trees are no longer even suitable for harvest. “They drill the trees and poison them with a syringe,” says Talib. Multiple reports from local and international sources support Talib’s accusations that Israeli settlers have, on multiple occasions, poisoned and uprooted Palestinian olive trees in the area. The ARIJ estimates that over 800,000 Palestinian olive trees have been uprooted by Israeli authorities and settlers in the West Bank since 1967.

The costs of occupation for Palestinians are pervasive. “Every day we’re seeing issues against humans, animals and land,” said Mayor Talib. There are certainly Palestinians who despise Israelis and even profess anti-Semitic views as a result of the conflict. But many also perceive nuance in their relations with Israelis.

“As a Palestinian, we don’t have a hatred for the Jewish or Israeli people,” said Mayor Talib. He specifically mentioned his gratitude towards Israeli Jews who work on behalf of Palestinian rights. “We eat and drink with each other.”

Annexation: A Dream or A Poker Chip?

A two-state solution, in which an independent Palestinian state exists alongside the Israeli state, is the most mainstream of the proposed solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “Land for Peace,” which would involve Israel ceding at least some occupied land to a future Palestinian state, is considered a likely component of any two-state solution.

While “land for peace” may be the most popular solution to the West Bank issue internationally, Israel’s current leadership campaigned this year on a far different idea: annexation.

Annexation refers to the extension of sovereign law. It is when a national government applies its authority to a conquered land. The Israeli government has applied Israeli law to its own citizens living in the West Bank but has never formally annexed the land.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu campaigned earlier this year on the promise to annex Israeli settlements in the West Bank. This would have made parts of Area C irreversibly part of the state of Israel and left the mostly Palestinian Areas A and B under their current administrative state (PA administration with Israeli security involvement). The small number of Palestinians living in Area C would not have been offered Israeli citizenship under the plan, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Many experts never regarded Netanyahu’s proposal as a serious one. Because annexation of land in Area A or B was never on the table, any realistic annexation plan would be mostly symbolic. “Annexing the settlements would be nothing but empty rhetoric,” said Professor Hassner. Annexation would involve a transfer of some power from military to civilian authorities in the settlements, but the land would be controlled by Israel and subject to Israeli law either way. “De-facto annexation is already in place,” said Sharona Weiss, Head of International Advoacy at the Israeli human rights NGO Yesh Din. Furthermore, at no point was an annexation map officially released nor was the military at any point involved in preparations for annexation.

The idea was still deeply polarizing among Israelis, with strong opposition from the left and Israeli Arabs. It gained support from many within the settler movement and the Israeli right-wing, though some on the far-right opposed it for not going far enough.

The move, if carried out, could have also jeopardized Israeli relations with the international community, including the European Union, according to the Congressional Research Service. These nations tend to regard both Israel’s continuing presence in the West Bank and any annexation proposals as illegal.

Ultimately, Prime Minister Netanyahu never went through with his stated goal of annexing parts of the West Bank. Instead, he abandoned the plan in August as part of a joint diplomatic deal with the United States, United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.

The deal, called the Abraham Accords, normalized relations between Israel and the two Arab nations. At the same time, Netanyahu announced his suspension of any West Bank annexation plans.

The deal marked the first formal diplomatic breakthrough between Israel and the Arab world since the 1990s, but it was met with anger by both Israelis and Palestinians living in the West Bank.

Palestinians held demonstrations against the deal, and the PA expelled the Emirati ambassador from the West Bank. While strongly opposed to annexation, many Palestinians opposed the deal because they saw the Emirati alliance with Israel as an abandonment of the Palestinian cause. “This is against our freedom,” said Mayor Talib.

Israeli settlers, meanwhile, viewed the deal as a betrayal by Netanyahu, who had campaigned on settlement annexation in 2020. “[Netanyahu] deceived us,” said Yesha Council Chairman David Elhayani in an official statement, citing multiple meetings in which Netanyahu had promised annexation this year. “The trust in [him] has expired.”

It appears likely that Netanyahu never intended to go through with annexation of any sort in 2020. He may have suggested it merely for political gain, though it is likely that he also used it as some sort of bargaining chip in his negotiations with the Gulf States Bahrain and the UAE.

“Anything interesting that has ever happened in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process happened because it caught everybody off guard […] the big steps forward had to do with negotiations behind the scenes,” said Professor Hassner.

Netanyahu did achieve a diplomatic breakthrough upon signing the Abraham Accords, one that the general public largely did not expect. But his achievement is overshadowed by the continued uncertainty faced by Israeli and Palestinian residents of the West Bank, whose political futures were used as poker chips in the negotiations.

Two Peoples, One Home

In some ways, current conditions in the West Bank do offer a glimmer of hope for a peaceful resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. “There is a significant amount of security cooperation between the Palestinian Authority and the Israeli government,” says Hassner. The PA and the Israeli government also cooperate on resource and water issues.

Violence in the West Bank has significantly declined since the Second Intifada. “I don’t feel like I’ve put my family in danger,” said Miri Maoz-Ovadia of her decision to live in the West Bank.

The West Bank stands in sharp contrast to the other Palestinian-majority territory, the Gaza Strip. Gaza is smaller and far more impoverished than the West Bank. It has been controlled by Hamas, a radical Islamist group, since Israel fully withdrew all military forces and settlers in 2005. Gaza’s borders have been shut to trade by both Egypt and Israel since the Hamas takeover, crippling the territorial economy. The feud between Hamas and Fatah, the moderate faction which controls the PA in the West Bank, has led to even more horrific violence in the occupied territories.

Today, the vast majority of terrorist violence against Israel originates in Gaza, not the West Bank. In addition, the vast majority of Palestinian civilian casualties in the conflict occur in Gaza.

West Bank residents are in a better position than those in Gaza but still must contend with internal restrictions on their freedom of movement and violations of their property rights. “In Gaza they live in big jail. Here, we live in small jail,” says Mayor Talib with a laugh.

Though people in both territories suffer economically and socially as a result of both the Fatah-Hamas conflict and Israeli policy, the West Bank’s relative affluence, secular administrative state and cooperation with Israel suggest that Palestinian statehood there is not an impossibility.

Future borders are just one of several key issues involved in a possible Israeli-Palestinian conflict resolution. Other important issues include the right of return for Palestinian refugees who were expelled or fled from Israel during the 1948 war and the question of whether a Palestinian state can or should have its own military.

In fact, some experts consider the border issue to be already resolved, in the sense that the outcome is fairly certain. “There are some giant settlement blocs that in all likelihood would be in a future state of Israel no matter what,” said Professor Hassner. “[But] I cannot envision a future in which there is not an Israeli state next to a Palestinian state.”

“What both sides lack for a peace agreement is a courageous leadership,” added Hassner.

The border issue is less defined in the minds of some Palestinians and Israelis living in the West Bank. An anonymous source at the Yesha Council expressed his belief via Zoom that the whole of the West Bank should become part of Israel in the future.

“[We’re] not giving up territory for some dream of peace,” said Maoz-Ovadia, in response to the idea that some Israeli settlements may be evacuated and abandoned as part of a future peace deal. “But a Palestinian government will still rule [in non-settled land].”

Many Palestinians, on the other hand, view annexation even of the most established settlements as a clear violation. “All the Palestinian people will agree on the 1948 lines,” said Mayor Talib, referring to the original borders set by the United Nations. “It’s not hard to get rid of settlements. They know they live in settlements.”

Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank have different religions, languages and historical memories. The Palestinian claim to the West Bank is based on centuries of continuous physical residency, while the Jewish claim is based on a millennia-old cultural tradition and ancient historical roots. Yet both sides see something in common in the West Bank: a home.

“Life here can be difficult and challenging but it’s also amazing,” said Maoz-Ovadia of her childhood hometown Neve Tzuf.

This competing claim is one of the primary sources of the intractability of the conflict. But one can also hope that a common interest in preserving their shared home could be the factor that finally brings the two sides together.

At the conclusion of our conversation, I asked Mayor Talib why, when he has the ability to live in the US, he chooses to continue living in a place where his basic rights are consistently violated.

“When you have your mother, your family, your land, what can you do?” he asked me. “It’s a homeland, do you know what a homeland is?”

Featured Image Source: Time Magazine

Comments are closed.