“When I went into a Whole Foods for the first time, I was shocked at how nice a grocery store could be,” says Lauren, a current undergrad studying in New York City who was born and raised in Montana. They continue, “I don’t think that most people understand the extent of the divide between urban and rural America.”

To a posh Californian or an urban New Yorker, rural America seems like a myth. Perhaps when many think of the “middle,” they envision open land, rolling tumbleweed and a lonely but patriotic American flag flying over an empty porch. At the heart of this vision are the farmlands, the tractors, a lineup of small, humble businesses and its workers. This, however, is not some cinematic romanticization of an America that we thought we left behind, but a reality for 60 million Americans residing in these lands. Dependent on small business, manufacturing and resource-based industries, such as agriculture and mining, the region is isolated, lacks opportunity and has fallen behind.

Rural America is a complex topic to tackle. In a country that flaunts the booming tech industry of Silicon Valley and the buzzing financial capital of the world of New York City, the condition of rural America is often the complete opposite. Rural America never fully recovered from the 2008 recession. Poverty rates are higher than in its urban and suburban counterparts. Educational attainment lags behind the rest of the country. Is it accurate to say that rural America has been abandoned?

It’s complicated. Rural America is confronted with a unique plethora of problems that don’t have an easy solution. First, rural America lags behind in development, as rural counties don’t have the same access to capital as cities like San Francisco or Seattle do. Economists have most recently credited economic agglomeration, the phenomenon in which newer companies tend to locate themselves where other companies are, as a large cause of this scarcity of capital and employment in rural areas. Due to economic agglomeration, the rural/urban divide has only exacerbated, with tech giants such as Amazon, Twitter, and Facebook all situated in cities like San Francisco and Seattle. Although newer, innovative companies settling themselves in rural counties would provide a fruitful source of jobs and would encourage capital flow for the region, there’s no incentive for the private sector to do so — economic agglomeration in urban cities allows for more American innovation and productivity as it attracts a highly educated pool of workers, something that rural counties don’t offer. As a result, rural America remains stuck in a time capsule, scarce of innovation and scant of opportunity, while urban cities profit off of these emerging, inventive companies.

Federal investment in teleworking and online degree programs seem like a possible remedy. If rural America lacks the competitive jackpot of workers that newer, up-and-coming companies are scouting for, teleworking and online programs can gradually close this rural/urban divide by allowing for remote work and by increasing the educational attainment of rural Americans that lags behind the rest of the country. A populace with higher paying jobs and higher educational attainment can attract more opportunities and more capital, which can catalyze modernization and economic opportunity in the region. However, with this possibility comes another complication: a concerning amount of rural Americans don’t have reliable access to the internet.

To begin with, the natural landscape of rural America makes it difficult to actually lay down wires for internet access. Thus, just as companies with high profitability don’t have the incentive to settle down in rural areas, internet companies don’t either, because having to work around the hills, trees and rivers of rural America is simply too costly. Not only that, some rural areas of America are susceptible to adverse weather conditions such as seasonal tornadoes and high winds, leading to the possible destruction of internet infrastructure, making internet access all the more inconvenient and expensive for companies. Although urban hubs like New York City and New Orleans are also prone to hurricanes and floods, these cities are home to large populations and big companies, both of which generate high income for internet companies. On the other hand, rural America is sparsely populated, making it an even less appealing investment. Lastly, rural poverty is rampant, much more than suburban and urban regions, meaning many rural Americans cannot afford monthly internet bills, especially when the lack of cable internet necessitates satellite internet access, driving up internet monthly bills up to $100, up $40 from the national average cost.

As a result, rural America is not only behind economically but is isolated as well. According to a Pew Research Center report published in 2019, only 63 percent of Americans in rural areas have access to broadband connection compared to 75 percent and 79 percent in urban and suburban areas. Although this is a considerable improvement from 35 percent in 2007, it is still unacceptable. Especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has forced nearly every aspect of our lives to become digital, reliable internet connection has become the portal to our workplaces and our classrooms. Without it, we become undoubtedly disconnected and left behind.

Teachers and students alike in rural areas have suffered tremendously because of this, both in a pre-COVID and current COVID context. Lauren, the Montanan mentioned at the beginning of the article, states that if the wind were ever too strong, power could be lost for “up to three days.” Alex Beene, an adult education teacher and ACT prep tutor in west Tennessee, estimates that over 70 percent of his students in his area don’t have reliable access to the internet. He suggests that these inequities have become more crystallized as a result of the pandemic. He states, “…you have employers who have sent them home, and they say ‘I can finally work on my diploma.’ Well, if you don’t have that internet access, you can’t do that either.”

But, even in a pre-pandemic world, educational attainment is one of the largest, if not the largest, disparities when comparing urban and rural America. Beyond access to reliable internet connection and financial resources, when it comes to education, there are physical barriers for many rural Americans to simply attend school. Lauren has expressed that because educational standards are on a “state-by-state basis,” it is inevitable that some states will take over others, leaving some behind. As it goes, rural America has gotten the short end of the stick.

“My parents even lied about our address growing up so I didn’t have to attend a one-room schoolhouse that only had one teacher and 25 students, ranging from 1st grade to 8th grade, all sitting in one classroom,” Lauren says. They also recall having to drive 150 miles away and book an overnight hotel in order to take one SAT II subject test — something unheard of in metropolitan, or even suburban, regions. They also mention that private organizations like College Board, which offers the SAT and AP exams, can also be blamed for widening the rural/urban gap, as these opportunities are not always made readily available to residents of rural countries the way it is in other urban and suburban regions. “My high school had no AP, IB, or honors courses,” Lauren says, “making college admissions, at that point, a joke.” Although Lauren eventually transferred to a high school outside of their hometown in Montana, among the class they would have graduated with, only about 20 of the 120 students went onto college.

While rural America is under no pressure to become the next mill producing top-notch scientists and academics for the country, as Lauren puts it, “anyone who wants to should have the opportunity to.” Yet, resources are undeniably limited. In a case-study of Nye County, Nevada, the country’s third-largest county by area (amounting to twice the area of New Hampshire), there is only one community college campus — one community college campus that’s responsible for cities up to two hours away. It fails to offer accommodating online options as well, with interactive video classes only available upon request. Even then, only 28 percent of the college’s students complete or transfer within eight years of enrolling, which lags behind the national average of 53 percent for community colleges around the country.

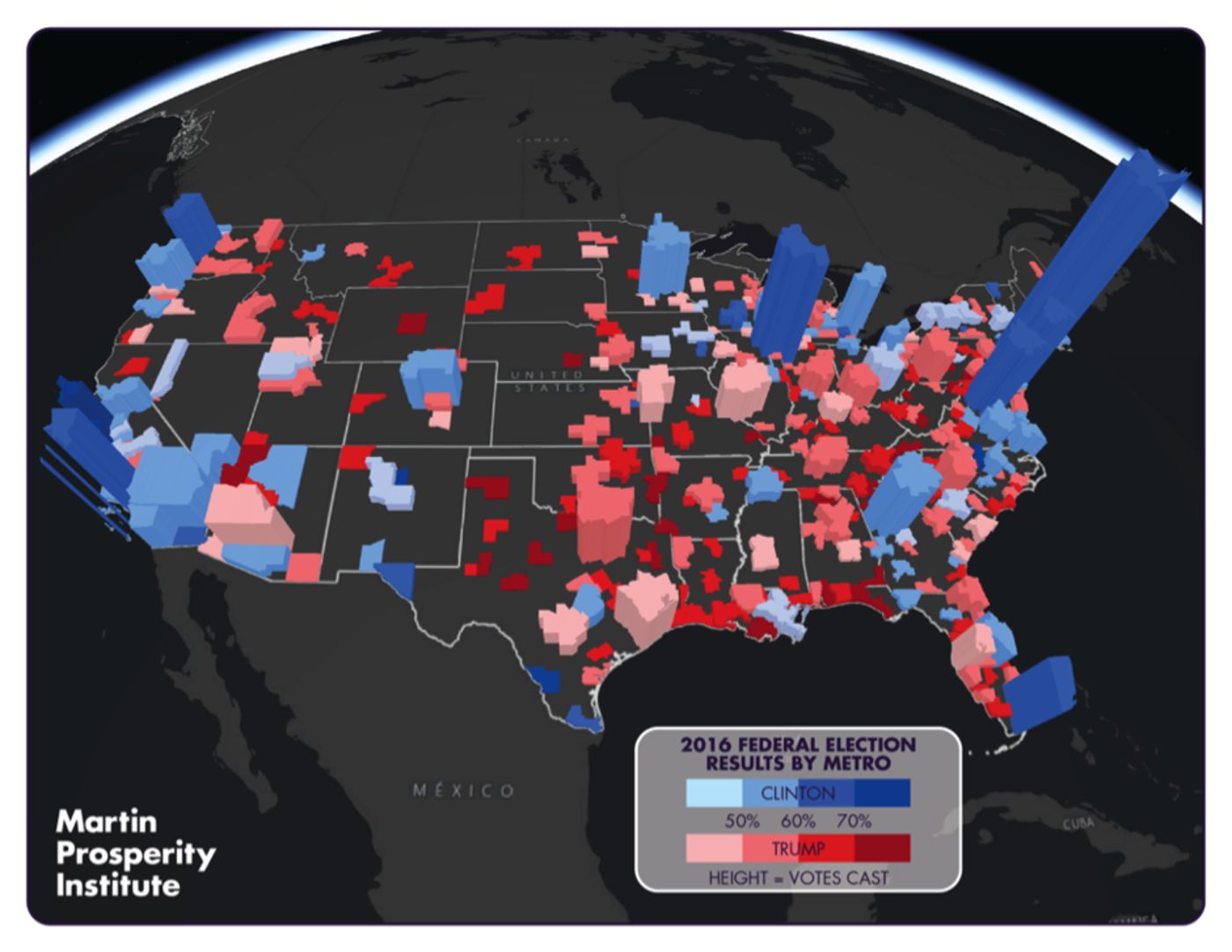

This rural/urban divide has dangerous political implications, particularly in its role in the intensification of party polarization. In fact, location, or where one lives, is increasingly playing a larger role in party identification. According to the “Urban Archipelago” theory, urban voters, not blue states, are the foundation of the Democratic Party, and rural Americans buttress the stronghold of the Republicans. This implies that party identity does not suggest a political preference for a set of policies like it used to, but rather that party identity is based now on this new, shallow system of self-identification based on where you live — if you live in San Francisco, Seattle, Portland or New York, you’re a Democrat, and if you live in the rural counties you’re a Republican. These aspects of this theory definitely hold. We observe this in most recent voting patterns — in both the 2016 and 2020 elections, rural regions loyally backed Trump and the Republican party, and cities ceaselessly voted blue, with few exceptions on either side.

But these new, geographical tensions we observe are dangerous because each party now nurtures completely conflicting versions of what America should and could be. Lauren believes that rural Americans often uphold the belief that they are the “backbone of the country” and the “foundation of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs in the U.S.,” in which they provide the country’s basic needs, such as food and water, due to their fundamental agricultural production and work in manufacturing. Although big cities spearheaded the country’s recent economic success prior to the pandemic, rural America believes they’ve provided the “framework.” Despite rural America’s contributions, however, they feel talked down to and not understood. In fact, 70 percent of rural Americans in a Pew survey agreed that Americans who don’t live in rural areas fail to understand their problems. On the contrary, urban Americans envision themselves at the forefront of progressiveness, revolutionizing a conservative America and modernizing every facet of the country in every way possible, a frame of thought which is susceptible to excluding or forgetting the 60 million Americans in the middle. The U.S. doesn’t need to be uniformly Republican or wholly Democrat to function properly, but it is clear that in recent years these two conflicting perceptions at battle have made it nearly impossible to have productive discussions.

Under the new Biden Administration, the question of rural America is not one that should be abandoned. From this new administration, we especially need legislation that eliminates the rural/urban disparity in broadband access in order to enable feasible distance learning and telemedicine. As the Broadband Data Act and Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act both passed in March this year have taken notable strides in allocating more federal funds into broadband development in rural America, the Biden Administration needs to continue and intensify this momentum to ensure that no American family is without it. In addition, the Biden Administration needs to focus on education reform that increases funding for K-12 schools in rural countries and urges state governments to improve their curricula. As Biden professed in his first speech after being elected, “I pledge to be a president who seeks not to divide, but to unify. One that doesn’t see red and blue states, but a United States.” Regardless of political party, attitudes or opinions, rural America should not be overlooked nor left behind.

Featured Image Source: CSG East

Comments are closed.