On November 8, 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump was welcomed to China by his “good friend” President Xi Jinping, who held an extravagant ceremony at the Forbidden City, home to the Chinese emperors for almost 500 years. Trump showed Xi a video clip of Arabella Kushner, Trump’s granddaughter, singing proverbial children’s songs in Mandarin. At the end of that year, the total trade volume between the United States and China reached a historic high of $660 billion.

Yet on April 3, 2018, Trump launched a full-scale trade war by slapping 25 percent tariffs on $50 billion of Chinese goods based on his dubious logic that a trade deficit was a sign of America being “ripped off.” Over the next two years, the two countries would engage in round after round of trade negotiations, which sometimes seemed to go well and sometimes broke off. The Chinese had a hard time understanding what Trump really wanted — massive agricultural purchases that would please his rural base, or structural changes in intellectual property (IP) protection and market openness? Trump’s own team had the same confusion, according to Bob Davis and Lingling Wei, authors of Superpower Showdown, for which they conducted hundreds of interviews with high-level officials in China and the U.S.

The bickering over COVID-19 between the U.S. and China has become emblematic of their choppy relationship for the past two years. In March 2020, Zhao Lijian, a hawkish Chinese spokesperson, tweeted that “it might be the [U.S.] army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan.” Since then, Trump has repeatedly used the phrase “Chinese virus” to direct attention away from his administration’s epic failure in controlling the virus. He also withdrew the U.S. from the WHO, which he accused of being a “puppet of China.”

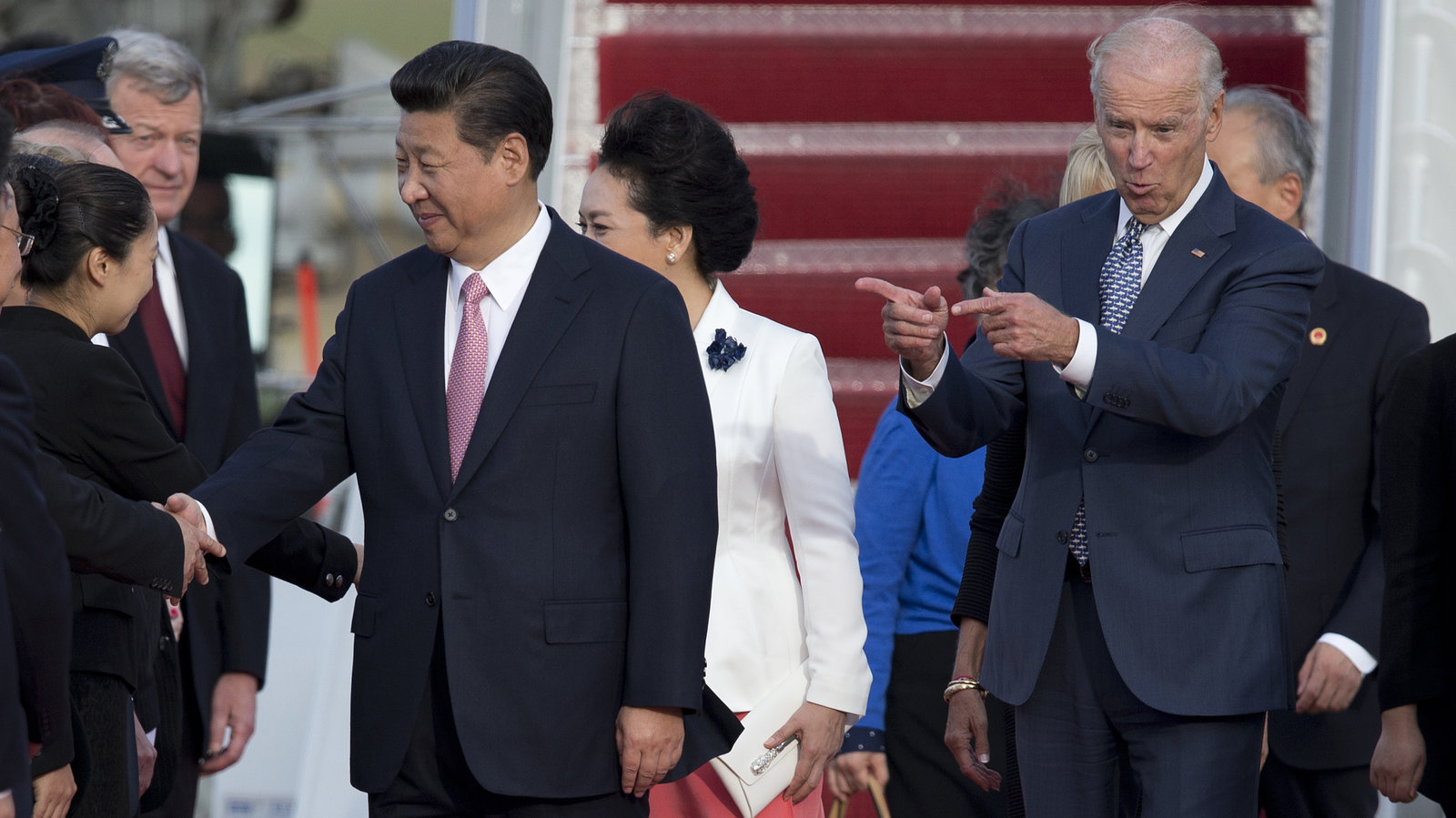

The damage done to U.S-China relations under Trump is deep and harmful. Will President-elect Joe Biden, who vowed to bring back decency, normalcy and democratic values, repair the cleft created between the two most powerful nations in the world?

Biden’s China team

On November 23, President-elect Joe Biden announced the list of his first batch of cabinet members. Antony Blinken, who served as chief foreign policy speechwriter under President Bill Clinton and as Deputy Secretary of State under President Barack Obama, is nominated to be the next Secretary of State. In a speech at the Hudson Institute earlier this year (2019), Blinken criticized Trump for helping China “advance its interests” by weakening U.S. leadership worldwide. He argued that the U.S. should “invest in our own competitiveness” to address the rise of China but should also “engage China and work with China, in areas where our interests clearly overlap.”

Jake Sullivan is Biden’s pick for National Security Advisor. He worked for Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden during the Obama administration. In an interview with the Asia Society in 2016, he said that the U.S. and China could work together on issues like North Korea and that “a strong, thriving China that is playing by the rules is very much in the interests of the U.S.” In a more recent piece for Foreign Affairs, he acknowledged that China had become a formidable strategic competitor. However, he believed, America’s policy should be “pro-democracy” rather than “anti-China.” To achieve this goal, the U.S. should assert its leadership in setting global norms and draw a fine line between cooperation and competition with China.

Biden himself is certainly more stable than Trump. He supported China’s bid to join the WTO when he chaired the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in line with bipartisan consensus at the time. During the 2020 campaign, he criticized Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods; however, it is unlikely that he will revoke the tariffs immediately after he takes office, given the political risks the move would trigger. Biden also said he would be willing to work with China on climate change, nuclear weapons and COVID-19. At the same time, he would promote a value-based diplomacy to unite U.S. allies against China’s approach to human rights and international norms.

Competitive engagement: the next phase of U.S.-China relations?

Biden’s foreign relations team — as well as his predecessor Trump — is rightly aware of the fact that the good old days of “naive” engagement with China are gone. President Xi, unlike his antecedents who chose to be either charismatic or low-profile, wants and needs to show his power. He has centralized all power at home while simultaneously projecting China’s reach abroad economically, militarily and even ideologically with his “China model.” The Chinese leadership no longer sees itself as a pupil learning from Professor America: it wants to compete with the U.S. on an equal footing.

Unfortunately, the kind of competition seen during the past several years has been a debasing one. The two countries are competing in terms of who is better at expelling foreign reporters, who is more capable of restricting the internet, who is more skilled at bullying neighbors and who is more able to use misinformation to stoke up antagonism against foreign countries. Some right-wing politicians — and even some Chinese activists and dissidents — have praised Trump for his confrontational approach, which they believe can curb China’s abuse of international norms. But Trump’s isolationist toughness has not made China subservient nor has the U.S. emerged better off than it was before this competition. In the face of China’s technological leapfrogging, Trump tried to cut funding for research; seeing the political unrest in Hong Kong, his bizarre policy of excluding Hong Kongers from the “green card lottery” punished ordinary Hong Kong people; instead of controlling the pandemic with science and transparency, he withdrew from the WHO and undermined American scientists and doctors. Trump’s assault on international institutions and domestic democratic norms has cost whatever moral high ground the U.S. once had.

Biden’s victory will not end the strategic competition between the U.S. and China, but it is likely that he will introduce a more positive kind of competition. The criteria for “winning” will now become “which country more staunchly uploads international rules and institutions? Which country contributes more to using technology to address climate change, world hunger, and global inequality? Which country invests more in research and development? Which country is a more responsible global leader?” This is the kind of competition in which two countries would engage and learn from each other, instead of pointing fingers in meaningless tit-for-tats. This is the kind of competition that would benefit the U.S., China and the world.

Featured image source: Carolyn Kaster/AP

Comments are closed.