At the conclusion of the NFL’s season in 2020, there was hope that this hiring cycle for head coaches would be different. At the time, of the 32 teams in the country’s most popular sports league, only 3 had black head coaches; a startling number for a league whose players are overwhelmingly black. Following the killing of George Floyd, the NFL implemented new diversity initiatives which sought to promote the hiring of individuals of color as head coaches. So what’s the number a year later? Two. After all the publicity and attention given to the issue, the number of black head coaches went down.

The NFL in many ways is its own bubble: teams have glitzy stadiums, amounts of money incomprehensible to most, and legions of fans. But when it comes to race, the NFL is the perfect microcosm of systemic racism in America: much like the country itself, the league is an organization whose employees — the players — are disproportionately black, and whose capitalists — executive, owners, and coaches — are disproportionately white. In the past twelve months, the league, and its head, Commissioner Roger Goodell, have put in place changes – some symbolic, some substantial – to address racial disparities. The apparent failure of these actions – and the reasons for their failure – is a lesson our society must learn from.

Causes

Perhaps the most glaring cause for the NFL’s racial disparities in coaching is ancestry. As The Athletic outlines: “At least one in seven NFL coaches in a supervisory role (non-entry level) is related to a current or former NFL coach.” That number rises to one in three when limited to head coaches. Indeed, some of the game’s greatest coaches today — such as Los Angeles Rams head coach Sean McVay and San Francisco 49ers head coach Kyle Shanhan — are themselves descendants of NFL legends. These familial ties that stretch back decades allow white coaches to accumulate generational knowledge and goodwill that their black peers often don’t have. The parallel to society writ large is chilling: inheritances are a key contributor to the racial wealth gap, and these intergenerational transfers of wealth give white families a safety net to fall back on. Coaching bloodlines are quite similar: through a combination of a recognizable name, nepotism, and a life immersed in the game, familial ties bolster individuals’ chances at becoming coaches.

Like many racial justice issues, one will hear a litany of excuses for this disparity. Teams will say that coaches are not a “culture fit,” or that they don’t “interview well.” But as Hall of Fame coach Tony Dungy says, this is simply a shield for owners to hide behind. It should be lost on no one that thirty of the league’s thirty-two owners are white: perhaps the reason black coaches are not a culture fit is because of the owners, not the coaches.

Another factor that shouldn’t be forgotten is the coaching pipeline. As it stands today, nineteen of the league’s thirty-two defensive coordinators are former head coaches. They are simply cycled over and over again, denying opportunity to the young, talented coaches of color waiting patiently for their turn. The league cannot combat the racial coaching gap without addressing this important front. Crossing sports for a minute, reporter Jared Diamond of the Wall Street Journal illustrated last year that managers in baseball are often catchers earlier in life, widely regarded as the most cerebral position in the game. However, because of racial biases, black players are often nudged away from becoming catchers, especially at young ages. Similarly, in football, black quarterbacks have been held back for years because of racist stereotypes. The reason this is so harmful is because it is fairly common for players to become coaches, so biases — even early on — in player development contribute to racial disparities in coaching.

The flashpoint in this debate has been Kansas City Chiefs’ offensive coordinator Eric Bieniemy. Bieniemy, an African-American, has commanded the league’s most prolific offense for a number of years, but despite an unmatched resume, Bieniemy has never been offered a head coaching job. His history has often been cited as the reason why: in 1993, he was arrested for harassing a female parking attendant. If the NFL were adopting a stringent zero-tolerance policy for harassment, that would be a welcome development. Unsurprisingly, that is clearly not the case here. In this hiring cycle alone, the Jacksonville Jaguars hired college football coach Urban Meyer, who was suspended for three games in 2018 because he likely knew about a domestic abuser on his staff. Meyer, who is white, didn’t apologize for the incident when he was hired; instead, he brought on a strength coach who has a history of using racial epithets, offensive slurs, and who dozens of black players have complained about for creating a hostile environment. Here, we see what is all too common in the criminal justice system: one standard for white people, and another for black ones. Unfortunately, in a society where Black Americans are nearly six times more likely to be arrested for drug-related offenses than their white counterparts despite equal usage rates, is it any wonder that Eric Bieniemy cannot get a head coaching job but Urban Meyer can?

Solutions

Currently, the main tool the NFL has in its diversity toolkit is the Rooney Rule. Implemented in 2003, the rule states that minority candidates must be interviewed for each senior level job opening. Data collected by renowned NFL writers Mike Sando and Lindsey Jones indicates that the hiring rate for coaches of color is now 15 percent, an increase from 2003 but still fairly low. While the rule has been somewhat effective, owners have sometimes bypassed it fairly easily, often handpicking a coach of choice from the beginning of the process. This year, the NFL worked to expand the rule to more positions, a step in the right direction.

In its nearly twenty year existence, the Rooney Rule has often been compared to diversity measures such as affirmative action and requirements that underrepresented minorities sit on corporate boards. The comparisons are apt: while both are well-intentioned efforts with some success, they are not a cure-all to the underlying problem. Because both the racial coaching gap and racial wealth gap have built up because of centuries of discrimination and inequality, the roots of these inequities must be addressed to truly solve the problems.

For the NFL, that means re-evaluating its coaching pipeline. Decision makers would do well to elevate young, innovative minds instead of the old and tired. Fortunately, a shift seems to be happening. The Chicago Bears hired Sean Desai as their defensive coordinator this year, an Indian-American. The San Francisco 49ers hired DeMeco Ryans, a former player, and a highly regarded defensive guru. And the one non-white head coaching hire this cycle was Robert Saleh, the first Muslim to hold such a position, and a young, beloved defensive coach.

In the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement this summer – the largest mass protests in American history – the NFL took action it considered strong: changing the name of the Washington Football Team, emblazoning the words “it takes all of us to end racism” on its end zones, and playing “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” before games. As welcome as these changes may be from a league that refuses to employ Colin Kaepernick, they’re ultimately a reflection of society. In the same way that our country’s collective response to the murder of George Floyd was depressingly performative – CEOs taking a knee in office spaces and corporations making Juneteenth a holiday – with little substantive changes to address the racial wealth gap, disparities in school funding or qualified immunity, so too has the NFL’s conduct been largely symbolic. The words “it takes all of us to end racism” ring hollow when the league cannot hire a single black head coach. And so for the abundance of talented black coaches in football, the promise of a head coaching job stays where it always has: one more year away.

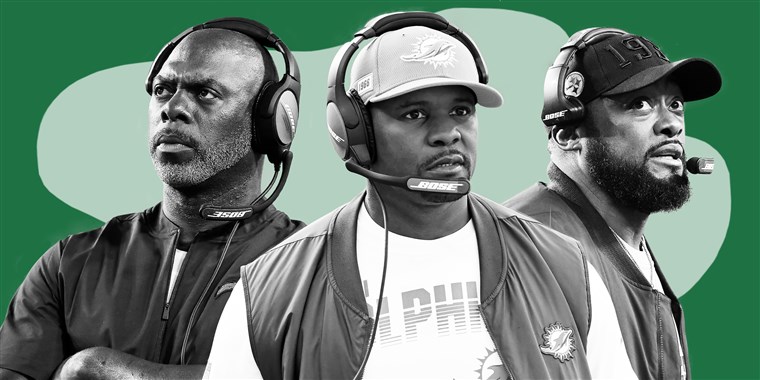

Featured Image Source: Getty Images

Comments are closed.