The median cost of a home in California is more than 2 times the national average at $600,000. In 2019, the state ranked 49 in the nation for a homeownership rate of 54%. San Francisco, Orange County, San Diego, Silicon Valley and Los Angeles top the list of the country’s most expensive housing markets. There is a critical housing crisis in America, and California is at the epicenter. From outdated zoning laws to a 40 years old piece of housing legislation and finally to the 2020 ballot, the policies that got us here have been continuously upheld– and progressive reforms shot down– in one of the nation’s most liberal states.

California’s poverty rate is the worst in the nation when adjusted for the cost of living, and the state accounts for a quarter of the country’s houseless population. To call this a crisis is an understatement, and there is no solution to it without constructing millions of new homes. McKinsey & Co. estimated in 2016 that California would need to construct 3.5 million homes in the next decade to tackle its housing deficit — though recent analysis suggests it could take until 2050 to reach that goal.

How did California end up with a housing shortage that was so profound? The short answer is that, for many decades past, housing policies were built to benefit the suburbanites, businessmen, and one particular generation above all else: the Baby Boomers.

The booming tech industry is bringing more and more people to California, increasing demand for housing while the supply remains insufficiently low. This has applied upward pressures on housing prices leading to a market in which houses are minimal and prices are high. California simply does not have enough housing units per resident, and it is only getting worse. In high-functioning housing markets, valuable land should encourage high-density, residential development in order to maximize revenue from rent. California, however, does not operate on this logic.

A 2019 study by the Terner Center for Housing and Innovation at UC Berkeley found that, while developers are incentivized to create high density housing to optimize profit and ultimately undertake a massive housing shortage, many suburban homeowners are relying on restrictive zoning laws to thwart those efforts. These ‘Not In My Backyard-ers’ claim that multifamily complexes will cause their homes to lose value and will endanger the ‘character’ of the neighborhood. Whatever the argument, it all circles back to subtle and direct forms of classism and racism. In comparison to homeowners, renters are typically younger, less wealthy and less white. Homeowners are – quite literally – gatekeeping their neighborhoods from these populations.

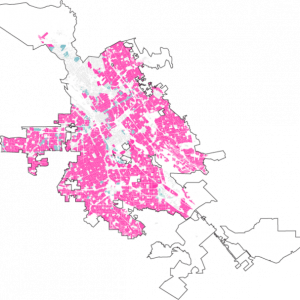

Many neighborhoods in California were downzoned – their established zoning laws changed to be more restrictive – in the 1970s to curb the creation of high density housing and implicitly segregate based on race and socioeconomics. In Los Angeles, an epicenter for houselessness, three-quarters of residential properties are zoned only for single-family homes; in San Jose, 94 percent. Without changes to these laws, not nearly enough housing can be built to match the urgent demand.

In December of 2018, Senate Bill 50 (SB 50) was introduced to the California Legislature by state Sen. Scott Weiner (D-San Francisco). The bill would have allowed for the construction of duplex, triplex and fourplex residential units in single-family neighborhoods without requiring additional local government approval. Zoning provisions are established and enforced at the city level, making them susceptible to pressure from affluent suburban families who are staunchly opposed to multifamily dwellings in their neighborhoods. Senate Bill 50 would increase the number of residences in California by overriding local zoning provisions, and could have been a crucial step forward in combating the housing crisis. But on January 31, 2020, the bill was defeated in the state legislature

The damage caused by zoning laws in California is more than palpable, but it would not have been as harmful on its own without a flurry of policies willfully committed to maintaining ‘status quo’ homeownership.

The housing shortage in California has been deepening since the 1970s due in significant part to a formidable piece of legislation passed in 1978: Proposition 13. Designed by businessman-activist Howard Jarvis, the bill was created to ease the overall tax burden and protect homeownership across California. It would be one thing to call this bill a wash, considering that Californians are among the most highly taxed people in the US today and our homeownership rate has rested around 55 percent for the last 30 years. In reality, however, this bill plays a crucial role in the perilous housing situation California currently faces.

Proposition 13 ensures that properties are only taxed only by a 2 percent maximum each year and can only be reassessed when sold. According to Zillow’s analysis of middle price tier homes in January of 2021, home values in California have gone up 10.5 percent in the past year. Thus, a maximum 2 percent increase in property taxes is nowhere near proportional to the market value.

While campaigning for Prop. 13, Howard Jarvis made the grand statement that

“The most important thing in this country is not the school system, nor the police department or the fire department… The right to have property in this country, the right to own a home in this country, that’s important.”

Promising the American Dream to rally voters turned out to be a sadly ironic tale. While those who have owned homes since 1978 are still enjoying their expensive properties without contributing their share in taxes, younger generations are struggling to become homeowners. And, the few that do own properties, are saddled with a much greater financial burden.

Older homeowners, who are typically wealthier than their younger counterparts, are disincentivized to sell their homes while their property taxes remain low leading to infrequent real estate turnover. When the next generation of younger and less wealthy people buy homes, they are saddled with a property tax that is actually reflective of the current market value, effectively subsidizing their parent’s generation of homeownership. What’s more is that all revenue lost from lower property taxes is more than offset by income and sales taxes. In effect, the overall tax burden is shifted to nonproperty owners, increasingly Gen-Xers and Millennials who cannot afford to buy homes.

What many voters tend not to understand is that these same tax breaks also apply to commercial real estate. However grossly ineffective it may be, Prop. 13 was passed to protect homeowners first and foremost, as Howard Jarvis made so abundantly clear. So why is it benefitting Disneyland and Facebook?

All in all, Proposition 13 is serving long-time homeowners and wealthy commercial businesses at the expense of everyone else. Still, there is something untouchable about it.

In a study released by the Public Policy Institute of California just before the 2020 election, homeowners were shown to account for 66 percent of likely voters in California. Proposition 15, a landmark bill and the first challenge on 1978’s Proposition 13 in forty years, was put on the ballot last November. It was soundly defeated.

“Like it or not, Prop. 13 has almost mythical powers against those who would assail it,” wrote Jon Coupal, president of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, after the 2020 election.

The purpose of Proposition 15 was a split-roll tax measure that would keep in place the protections for homeowners, but remove those for commercial properties valued over three million dollars. Coupal may have a point that Prop. 13’s powers are indeed mythical, given that in 2020, Proposition 15 was voted down by many who serve to benefit from it.

Proposition 15 could have generated over $12 billion in revenue for the state. This money would have supplemented tax deductions for personal income and property taxes. 60 percent would have gone to counties, cities, and special districts. 40 percent, or close to $5 billion, would have gone to the California school system.

The suffering public school system in California relies on property taxes as their main source of revenue. With the taxes so low due to Prop. 13, our public schools are paying the price. The rejection of Prop. 15 leaves California schools and community colleges without the prospect of increased funding in the midst of a pandemic, something that has inevitably affected low-income students disproportionately.

In what is widely considered the country’s most liberal state, we continue to put business interests on the ballot and come up short for our most vulnerable communities. In 2020 alone, we saw the failure of Proposition 15 addressing the housing crisis, the failure of Proposition 16 addressing racial equity, and the passage of Proposition 22 after Uber and Lyft spent $200 million getting it on the ballot.

Political decisions in California frequently tend to favor the status quo, and disheartening statewide policies – or a lack thereof – admittedly make the outlook seem bleak. But there is still hope yet to come, especially on a local level.

Already in 2021, the city council of Berkeley voted unanimously to approve a resolution that would ban the use of exclusionary zoning practices by 2022. This is a decision of resounding significance, especially when considering that Berkeley’s Elmwood was among the first places in the US to be zoned for single-family living in 1916. Such zoning laws account for 82 percent of residential land in the Bay Area, but fortunately this historic move in Berkeley is supported by a whirl of similar legislation in Northern California. Earlier this year, Sacramento passed a unanimous decision to allow for up to four units on nearly every residential lot. South San Francisco and San Jose are considering similar upzoning policies to weaken restrictions on multifamily complexes. Grassroots organizations across California, such as YIMBY, are saying ‘Yes in My Backyard’ to combat the housing shortage by working with state and local legislators to increase affordability and availability. We must also not forget that a new generation of voters are maturing. Increasingly Gen-Xers and Millennials will be putting their interests on the ballot, hopefully leading to progress within California’s institutionalized property and tax laws.

The California political sphere does not only have to be for the wealthy and powerful, and progress is clearly on the horizon. There can be real changes and, if history serves as a warning, there has to be. Houslessness will continue to increase and residents will continue to be displaced until we can rally against this worsening crisis, and forcefully undo the ‘mythical powers’ of past policies that got us here.

Featured Image Source: KTLA

Comments are closed.