Twenty minutes south of Birmingham, just up the road from a state park, lies the town of Bessemer, Alabama. Termed the “Marvel City” for its industrial prowess, and named for the British inventor who created the famous steelmaking process, Bessemer has since fallen on hard times. Deindustrialization gutted the region, and more than 27 percent of its population now lives below the poverty line. Then, in 2018, with the allure of a federal tax break, this small municipality of less than 28,000 attracted the richest man in the world: Jeff Bezos. That year, Amazon agreed to build a $325 million fulfillment center, employing 1,500 workers with a starting wage of $15 an hour, health benefits and dental coverage.

Despite that investment, Amazon has been notoriously hostile to any labor organizing in its nearly thirty year history. None of its workers have ever successfully unionized, and the company has used algorithms to track any potential unionization. Against this backdrop, a tale of David and Goliath emerges. The 5,800 people who work at the warehouse in Bessemer are on the verge of joining their local chapter of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. As The New Republic reports, the mostly Black workforce is “sick of exhausting productivity goals and relentless monitoring by management,” and is set to hold a union election that ends on March 29. Organizers expect the vote to be close, and Amazon certainly hasn’t made it easy. The country’s second largest employer has bombarded Bessemer with anti-union posters, even hanging them up on bathroom stalls. A few months ago, amid the pandemic, the corporation petitioned the National Labor Relations Board to hold the vote in person.

Source: The Daily Beast

The vote comes at a pivotal time for the labor movement. A combination of forces — Supreme Court rulings, right-to-work laws, deindustrialization, the gig economy, and corporate consolidation — have caused union density in America to fall from its high of 35 percent in the 1950s to 10 percent today. This sharp drop-off has had profound consequences for the entire American economy, contributing to increases in income inequality, wage stagnation, and the racial wealth gap. Still, the grassroots organizing exemplified by Bessemer’s workers marks a revitalization of the labor movement in recent years. Approval of unions has reached its highest point in 17 years. The House passed the Protecting the Right to Organize, or PRO, Act a few weeks ago, the most pro-union piece of legislation since the New Deal. And just last month, President Joe Biden delivered a strong statement in support of free and fair union elections. In this muddied political environment, it’s worth asking: Where does the labor movement stand today?

The Labor Movement, A Brief History

The history of American labor organizing dates back several centuries. In the 1800s, as industrial capitalism grew, unions fought back through famous actions like the Pullman Strike, which froze most of the national rail system. Various organizations — such as the American Federation of Labor, Industrial Workers of the World and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union — grew in power. Over the next few decades, unions agitated for basic rights that are commonplace today: the eight hour workday, a minimum wage and workers’s compensation.

The pinnacle of the movement came during the New Deal. The Wagner Act, signed in 1935 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, gave workers the right to unionize, granted those unions the power to collectively bargain and created the National Labor Relations Board to tamp down on company interference with workers. Three years later, the Fair Labor Standards Act established time-and-a-half overtime pay, a 25 cent minimum wage and a 40-hour workweek. These laws were tremendous victories for the labor movement, and union density grew after their passage.

Following a wave of strikes in the 1940s and Republican gains in the 1946 midterms, however, anti-union sentiment expanded. In 1947, Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act over President Truman’s veto. The statute allowed states to pass right-to-work laws and significantly curtailed unions’ ability to strike. A few years later, private sector unions would begin their decades-long tumble.

Intense disapproval of unions manifested itself around the stagflation crisis of the late 1970s. As Eric Levitz of New York Magazine lays out, “a consensus formed among policymakers that the excessive bargaining power of American workers had broken the economy.” The early 1980s recession that resulted was disastrous for the labor movement, and the idea that unions were part of the problem soon became economic orthodoxy. In 1981, President Reagan infamously fired 11,000 air traffic controllers who had gone on strike — another tremendous blow to the labor organizing.

The skepticism of unions wasn’t limited to Republicans either. Both Presidents Clinton and Obama drew the ire of some labor leaders, such as American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations leader Richard Trumka, who said they were “disappointments to organized labor.” That mold of political and economic thinking helps explain the slow decline of private sector unions over time (the story of public sector union growth is quite complex, but likely results from changes in labor law in the 1960s).

The Current Outlook Seems Bleak

Recent economic trends put the importance of unions in sharper focus. Deindustrialization — the past half-century’s long grind of shuttered factories and declining manufacturing jobs — has led to the disappearance of high-paying, union jobs in sectors like steelworking. As University of Chicago Professor Gabriel Winant illustrates in a new book centered on the city of Pittsburgh, filling the void left by deindustrialization are lower-paying, non-union jobs in custodial services and care work professions. As a result, the drop in unionization is partially responsible for the rise in income inequality.

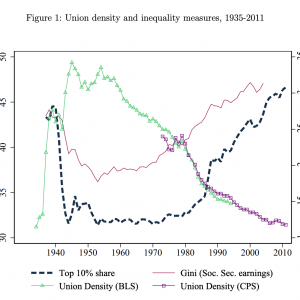

As union density has dropped, inequality has rapidly risen.

Source: Farber, Herbst, Kuziemko & Naidu

Another novel trend contributing to the decrease in unionization is the rise of the gig economy, highlighted by companies such as Uber and Lyft. In the context of the labor movement, the greatest source of tension has been the classification of workers: are Uber drivers full employees or only independent contractors? The flashpoint in this debate was Proposition 22, which overturned a California law listing gig workers as full employees, with rights to a minimum wage and benefits. Uber, Lyft and DoorDash combined to spend more than $200 million on the campaign effort for Proposition 22, and the vote was a success for those companies by a wide margin: decreased worker benefits and slashed wages.

Proposition 22 was a monumental blow to the labor movement. The initiative stripped workers of health benefits, the right to sue against sexual harassment, and general labor protections — effectively erasing decades of rights that were hard won by the labor movement. The response to its passage has been alarming. Large grocery chains have floated the idea of replacing delivery staff with DoorDash subcontractors, and similar proposals may be on the ballot in Illinois and New York in the next few years. According to Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi, Uber will “loudly advocate for new laws like Prop. 22” going forward.

Unions in California responded with a lawsuit, which could take years to resolve in the courts. They have also pushed for the Biden Administration to take stronger legal action against worker misclassification, but what such a policy would look like in practice is still unclear. In short, while labor’s reaction to Proposition 22 has been swift and fierce, if any material change is going to happen, it will have to come from robust federal legislation.

Proposition 22 is only the latest in a string of losses for unions. The Supreme Court has been no friend of the working class either. Two cases in particular stand out: Epic Systems v. Lewis (2018) and Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (2018). In the former, the Court held that individual arbitration agreements — wherein employers and employees resolve disputes about, say, wage theft or discrimination outside the formal court system — are legal. The decision is extremely consequential because the labor movement derives strength from employees collectively bargaining with employers. However, this case opens the door to companies using divide-and-conquer tactics through individual arbitration where the balance of power is tipped against the worker. Collective arbitration was a hard-won union victory first laid out in the Wagner Act nearly 100 years ago; the Supreme Court guttedit with one decision. The upshot is clear: 25 million employees are now subject to employer-friendly individual arbitration agreements.

The Court’s decision in Janus drew much more attention. In that case, a 5-4 majority held that public sector unions compelling dues from members was an unconstitutional infringement on free speech. While the impact of Janus hasn’t been the fatal blow observers feared — many dues-paying members have continued supporting their unions — there has still been a substantial drop in dues from nonmembers. The absurdity of the Janus verdict was put best by labor journalist Jonah Furman this year: employees not paying dues but still receiving the benefits union representation is akin to not paying taxes but still receiving Social Security.

If the current situation wasn’t troublesome enough, conservative state legislatures have piled on with a flurry of right-to-work laws. Twenty-seven states now have them in some form. Simply put, these laws mean that no person must join a union or pay dues in order to be employed. The common justification for right-to-work laws is that they create more jobs, but there is no indication that has materialized. Instead, in an era of increasing inequality, lawmakers have further crippled worker power.

The results are particularly pernicious because of what unions have achieved over the years. Their impact goes beyond supply and demand or dollars and cents. As writer Corey Robin explains, “We’re working way too many hours for too little pay, and in the remaining few hours (minutes) we have, after the kids are asleep, the dishes are washed, and the laundry is done, we have to haggle with insurance companies about doctor’s bills, deal with school officials needing forms signed, and more.” In an era where economic systems have grown more dystopian, the labor movement offers a way out: a living wage, paid family leave, and a flexible workweek. Rather than supporting unions, our government policy over the past half-century has weakened them significantly.

Is There Any Hope for Unions?

The situation for the labor movement today is rife with negativity. But 2021 has offered much-needed hope, from both a bottom-up and top-down perspective. In March, the House of Representative passed the PRO Act, a sweeping law that would significantly tip the scales toward workers. Richard Trumka, the president of the AFL-CIO, summed up the bill’s importance aptly: “if you really want to correct inequality in this country — wages and wealth inequality, opportunity and inequality of power,” he said, “passing the PRO Act is absolutely essential to doing that.” Among other things, the bill forbids employer retaliation against workers for engaging in union activity, takes the employer out of the process in setting union election rules, bans collective arbitration waivers (the crux of the Epic Systems case), and classifies many people labeled as independent contractors as employees (a direct rebuke to the corporate backers of Proposition 22). The bill is currently held up in the Senate, and won’t be passed without filibuster reform since no Republicans are expected to support it (in the House, only five Republicans joined every Democrat in voting yes). Regardless, the impact the law would have on unions is enormous.

In addition to the PRO Act, the statements by President Biden in support of workers’ right to collectively organize is a significant break from predecessors. The president has also tapped numerous pro-union policymakers to fill his cabinet (his Secretary of Labor, Marty Walsh, is a former local labor union president himself). And on his first day in office, President Biden fired the general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board, a notorious union-buster. Almost none of it would be possible without the work of unions at the ground level. Even President Franklin Roosevelt, arguably the most pro-union president in American history, needed unions to force his hand. As Richard Yeselson documents in The Atlantic, President Roosevelt told a group of labor activists who were fighting for expansive legislation four simple words: “make me do it.”

Which brings us back to Bessemer. Fifty-one-year-old picker Darryl Richardson has given a number of interviews over the past few months. During an interview published in The Guardian, Richardson described the conditions at the Amazon warehouse in Bessemer: “You don’t get treated like a person… You don’t have time to leave your workstation to get water. You don’t have time to go to the bathroom.” There is no better explanation for the importance of the Alabama union drive than that, and the Biden Administration’s signals in support of it are very encouraging. But President Biden certainly cannot act alone. He needs popular support and a legion of voices calling on him to act — to make him do it. Those thousands of workers in Bessemer taking on the richest man in the world just might.

Featured Image Source: SOPA Images

Comments are closed.