Traditionally, medical institutions and systems are portrayed as places of cures and remedies, but what if they are actually major sources of health issues, woven into a broader system of inequitable access to healthcare and distribution of basic human needs? Well aware of this contradiction, the Black Panther Party (BPP), led by Huey P. Newton, started to take matters into their own hands back in the 1960s and developed community-led programs that targeted many of the epidemiological issues afflicting disadvantaged communities. By creating free medical clinics, a free lunch program, and sickle cell screening centers (in addition to other projects and programs), the organization was able to provide underserved communities and communities of color (often one and the same) with some of the same health services that their wealthier, whiter counterparts had. The fact that the United States’ healthcare system had contributed to significant disparities in health outcomes between neighborhoods of varying socioeconomic status was made plain and clear, through both lived experience and documented data. So, the BPP intervened to provide the health services that the government would not, in order to improve life outcomes (in stark contrast with the violence that the media and literature has focused and continues to focus on). While textbooks and articles like to dance around the Black Panther Party’s provision of critical health services and ignore (or even glorify) the government’s blatant subversion of the organization, the narrative of the BPP’s work is telling of the inequities that continue to shape the demographics of health, while also pointing to innovative solutions. While the work of the Black Panther Party was commendable and critical, it really should not have been necessary. If health is in fact a human right, why were many communities denied it in the first place?

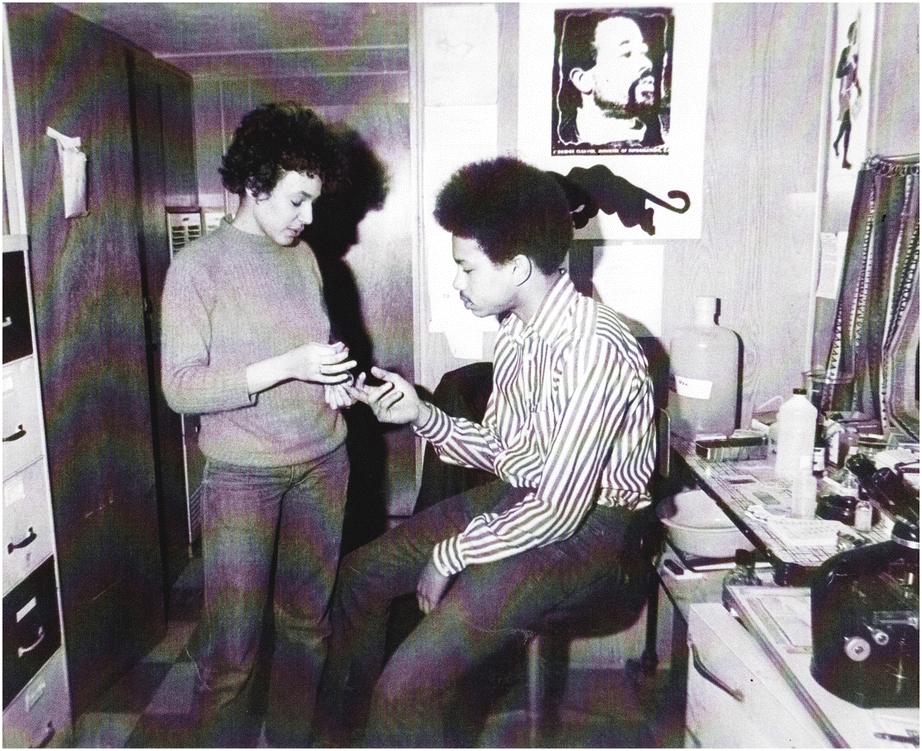

Demonstration of sickle cell screening at a Black Panther Party medical center in Boston, Source: Mary T. Bassett, “No Justice, No Health: the Black Panther Party’s Fight for Health in Boston and Beyond”

This question is as relevant today as it was back in the 1960s and 1970s. In the face of a global pandemic, the disparities in health outcomes between various socioeconomic and racial groups have been notably magnified. According to the CDC, “A study of selected states and cities with data on COVID-19 deaths by race and ethnicity showed that 34% of deaths were among non-Hispanic Black people, though this group accounts for only 12% of the total U.S. population”. This should come as no surprise given the present disparities that exist across the social determinants of health, and these issues will continue to persist, even once the coronavirus is controlled. Many individuals in the country still lack access to quality, affordable health care and are subject to environments that degrade their health and well-being.

![]()

Social determinants of health, Source: CDC, “Social Determinants of Health”

Health outcomes are a function of a variety of inputs — including housing, transportation, and collective efficacy; medical care is only one part of the picture. So, when examining novel policy approaches for improving health and preventing morbidities, it is important to look beyond the clinic. Housing and neighborhood conditions, for instance, are key determinants of health outcomes. Is ample green space present in the community? Will high levels of pollution give teenagers asthma? Are children in the community in an environment that will enable them to learn and grow?

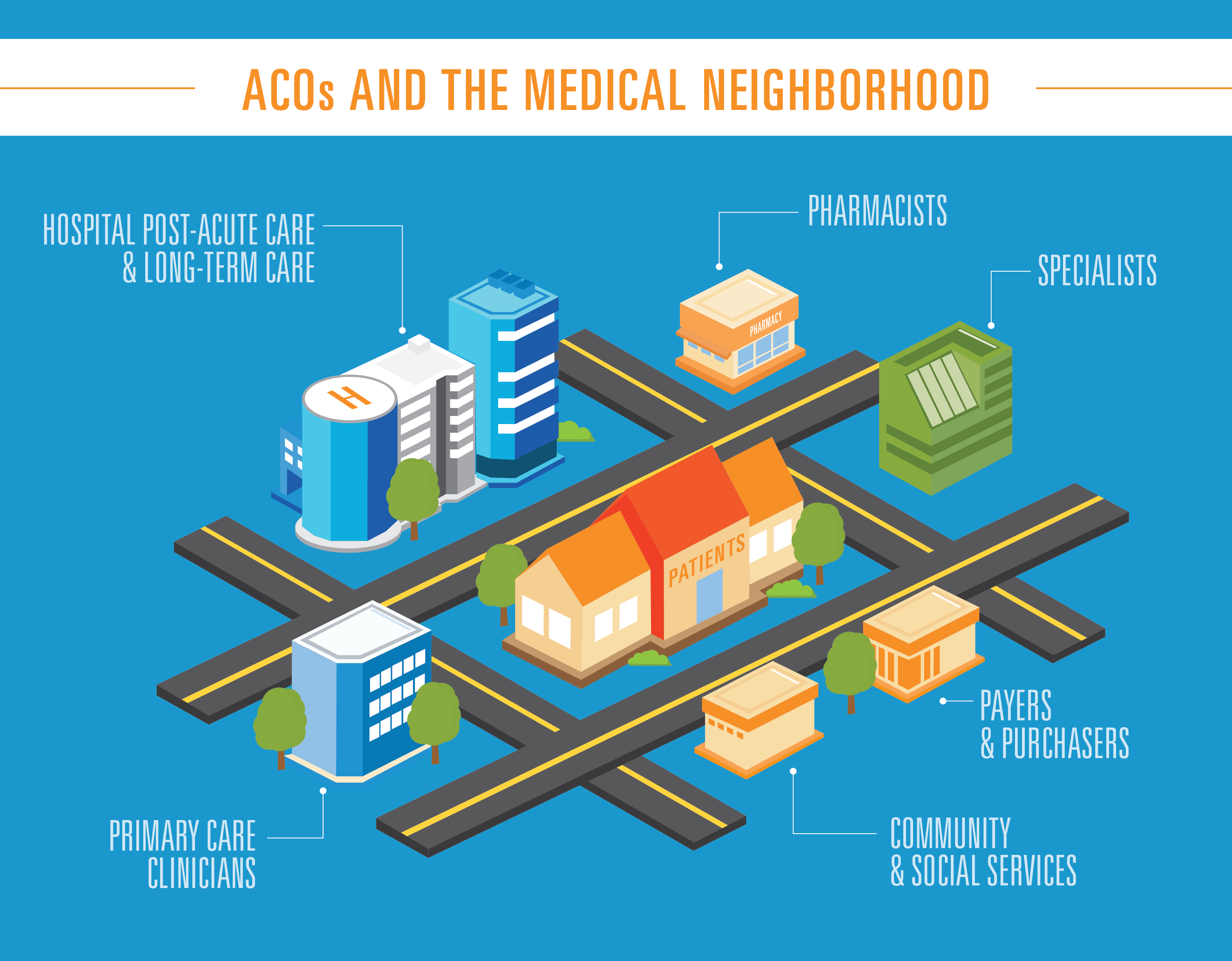

Many coalitions and strategies have been created that target health risks both before and after issues arise, in an effort to develop a comprehensive approach to improve health. One such approach has been the development of Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), funded under Medicare. ACOs are usually comprised of a group of healthcare providers who receive funding that is contingent on patient and community health outcomes. As such, these ACOs will often take preventative interventions, such as the development of affordable housing and service programs, so that they can address community health in a more cost-efficient and health-effective manner.

Accountable Care Organization ecosystem, Source: Blue Cross, Blue Shield, “Bright Idea: How Accountable Care Organizations are changing healthcare”

Take, for instance, The Healthy Neighborhoods, Healthy Families Initiative (HNHF) — in partnership with community-based organizations such as local churches and nonprofits, Nationwide Children’s Hospital developed a “neighborhood as a patient” approach and was able to invest over $22 million into the Southern Orchards neighborhood in Columbus, Ohio. Like the BPP, HNHF engaged with community members to develop niche strategies to improve life outcomes. As for the neighborhood itself, due to past housing discrimination, the construction of a major highway through the community, and the resultant concentrated poverty, Southern Orchards was one of the most at-risk neighborhoods in Ohio.

This is where Nationwide Children’s Hospital came in. As an ACO, the hospital was accountable for the health outcomes of all children on Medicaid in the community — and by extension, responsible for the health of the community itself. There was then a clear need on the part of the hospital to invest in neighborhood conditions instead of constantly providing band-aid fixes. Band-aids cannot prevent asthma, diabetes, adolescent depression, and dismal graduation rates; a holistic neighborhood intervention based on community input and preventative strategies is naturally the better approach. So, the HNHF partnership worked to construct new affordable housing units while also providing funds for the renovation of existing homes in order to improve energy efficiency and quality of construction. Beyond this, job-training programs, in addition to a host of other services and the renovation of the built environment, were provided. Progress has already been observed in the form of heightened high school graduation rates, lowered vacancy levels, and decreased violence in the neighborhood — a rather optimistic outcome for a project designed to counter a problem decades in the making. As a 2018 article in Pediatrics explains, “A segregation problem that took 80 years to manifest will take more than 8 years to resolve, but the collaboration is collecting emergency department data, crime data, and local school data to evaluate whether local children are faring better over the next 3 years.”

Healthy Neighborhoods Healthy Families Initiative (HNHF), Source: Kelly Kelleher, Jason Reece and Megan Sandel, “The Healthy Neighborhood, Healthy Families Initiative”

Now, with a new administration in the White House, the question is whether or not extra funding will be provided for innovative programs and health structures such as ACOs, and whether health care institutions (both conventional and unconventional) will be incentivized to equitably distribute quality care. In light of the pandemic, President Biden signed an executive order that establishes a “Special Enrollment Period” (SEP) for coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) healthcare insurance marketplaces. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) even launched a $50 million initiative to spread awareness of the SEP and to work with community-based institutions to encourage enrollment. In the face of the pandemic and partially as a result of it, around fifteen million people in the US (around 3.5%) are currently without health-insurance and eligible for healthcare enrollment through the ACA Marketplace (with a sizable fraction eligible for free coverage). So, providing the opportunity for these individuals and households to sign up for affordable health coverage (and telling them about it) is most definitely a step in the right direction. The executive order also confronted barriers to healthcare, established by the Trump Administration, which work to limit access to services such as abortions and health care coverage as a whole. Furthermore, the $1.9 trillion Rescue Plan includes provisions to increase healthcare subsidies and expand the child tax credit.

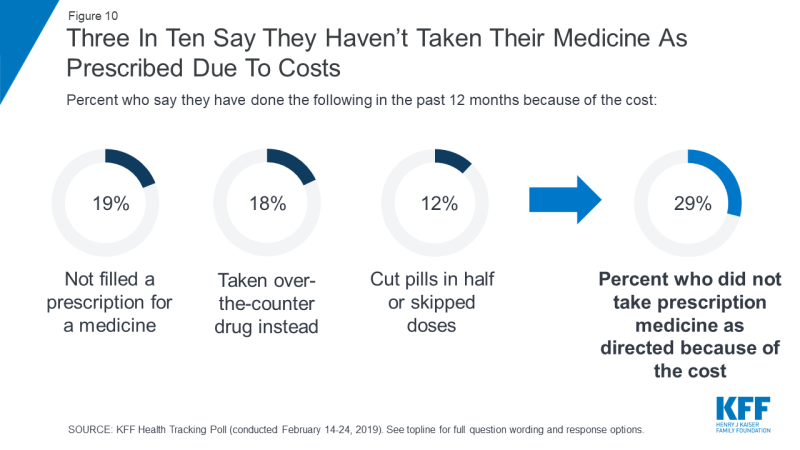

It is also informative to look ahead at what is on the agenda for the next four years. One primary component of the administration’s plan for achieving better health outcomes is targeting the pharmaceutical industry — how can we begin to talk about improving health if solutions are financially out of reach for much of the population? For instance, studies have suggested that one out of every four diabetics in the country cannot afford their insulin treatment. As such, the administration is planning to expand the capacity of Medicare to negotiate drug prices with pharmaceutical companies. Furthermore, there are plans to regulate price increases for existing therapeutics and to limit launch prices for newly developed drugs that have little to no competition. Leveraging limited supply against essential demand is unethical to say the least, and while current advancements in biotechnology and medicine are remarkable, it is imperative that attention is not only focused on the science behind these advances, but also on the equitable distribution of these treatments so that everyone has a stake in this scientific progress. Market regulations, such as the ones proposed by the Biden administration, will be essential for improving health outcomes and promoting health equity.

2019 survey conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation, Source: KFF Health Tracking Poll – February 2019: Prescription Drugs

These pushes to regulate Big Pharma are somewhat narrow in scope, however. Structural change needs to be made to mitigate the need for these drugs and treatments in the first place. Accordingly, there are a variety of other initiatives in development such as restoring federal funding for Planned Parenthood, doubling investments in community health centers, and rather significantly, providing a new and affordable public healthcare option that would act similarly to Medicare and entirely cover services such as primary care.

With these interventions to increase access to healthcare, some are saying that this may pave the way for a single payer insurance system in the U.S. — akin to what can be found in the U.K. and Sweden (although, admittedly, it might be a long time before we see this). Regardless, it is still crucial that the administration considers equity and looks through a racial justice lens when devising and implementing new strategies, so that we can start to break away from unjust trends in healthcare that have been incited by centuries of disinvestment. By coupling increased government funding with innovations in the way that we target, distribute, and provide healthcare, it is hopeful that we will continue to see progressive changes made to the ways that we improve and equalize health outcomes in this country.

Featured Image Source: RevCycleIntelligence