“Two-thousand and eighty-five votes in favor, zero against, and one abstention. [The bill is] passed!” On March 11, 2021, nearly 3,000 Chinese lawmakers passed the “decision on improving the electoral system of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region” at the Fourth Session of the 13th National People’s Congress (NPC). The NPC, according to China’s Constitution, is the highest organ of state power, and its plenary session is convened once a year in early March in Beijing.

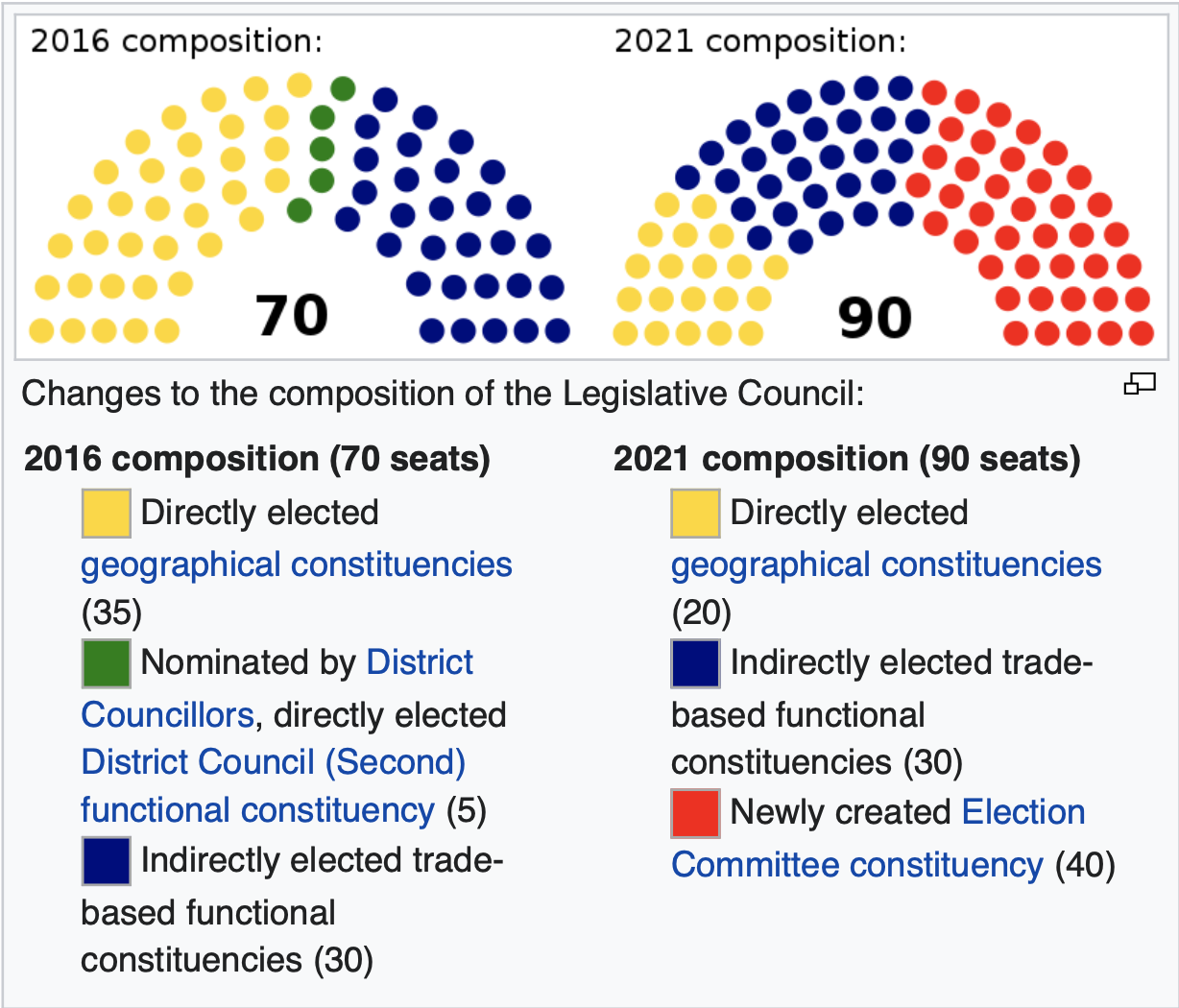

The decision is another major overhaul of the constitutional-legal order in Hong Kong after the Standing Committee of the NPC (NPCSC) imposed the Hong Kong national security law in June 2020 to curb anti-government actions that allegedly threaten national security. As part of the March 11 decision, the Legislative Council (LegCo), Hong Kong’s legislative branch, will be expanded from 70 seats to 90 seats. Forty of the ninety seats will now be elected by the Election Committee (EC), an electoral college composed of members from Hong Kong’s professional, religious, and political sectors whose primary task, prior to the new reform, has been to nominate and elect the Chief Executive. Historically, the Election Committee also elected a few lawmakers in 1998 and 2000, but those EC seats were quickly phased out and replaced by popularly voted seats as part of the gradual reform to make the legislature more democratic. This was in accordance with Articles 45 and 65 of the Basic Law—the de facto constitution in Hong Kong since 1997—which stipulate that the method for selecting the Chief Executive and Legislative Councilors shall be reformed “in accordance with the principle of gradual and orderly progress” until universal suffrage is achieved. Today, however, Beijing is bringing EC seats back to LegCo, and by a large number.

The composition of the Election Committee will also change, effectively enlarging the number of positions appointed by the government. Meanwhile, a “candidate qualification review committee” will be set up to decide who can run for Chief Executive, Election Committee Member, and Legislative Councilor. Additionally, candidates must now swear to uphold both the Basic Law and the national security law. All these reforms add more certainty that pro-Beijing lawmakers will occupy an absolute majority in the legislature, giving Beijing uncontested control over Hong Kong politics.

Why now, after over two decades of relative autonomy for Hong Kong, is Beijing choosing to assert its authority in this way? To understand why this change is happening, we must first trace the context and trajectory of Hong Kong since the handover in 1997.

Hong Kong in the Pre-National Security Era: Two Major Policy Shifts, Three Phases

Hong Kong, a British colony for 150 years, was returned to China in 1997. Under British rule, Hong Kong citizens enjoyed broad freedom under common law but only had a very limited level of democratic participation in policy- and law-making. Beijing inherited much of the election system the British left behind in 1997 and promised gradual, progressive reform to achieve universal suffrage in the new Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR). Since that time, but before the imposition of the recent national security law, Beijing’s policy on Hong Kong can be divided into three phases. In the first phase (1997-2003), Beijing dutifully hewed to its promise of “One Country, Two Systems” laid out in the Basic Law. Consciously avoiding making comments on Hong Kong’s internal affairs, Beijing sought to assure Hong Kong citizens that the city’s rule of law and prosperity would continue to thrive. However, in 2003, 500,000 Hong Kong citizens took to the streets to protest against the SAR Government and forced it to indefinitely shelve its first—and so far its only attempt at—local national security law legislation, the passage of which is a constitutional responsibility entrusted to the SAR Government by the Basic Law. Beijing realized that its non-interference policy had not worked out as it had expected; it thus decided to take a more active role in providing more benefits to Hong Kong, hoping to win support from the Hong Kong people.

Chinese premier Wen Jiabao’s visit to Hong Kong inaugurated the second phase (2003-2014) of Beijing’s policy towards Hong Kong. On June 29, 2003, during Premier Wen’s visit, the Central Government and the Hong Kong government signed the Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), whereby Hong Kong products and services would enter the vast mainland market duty-free. A month later, Beijing launched the Individual Visit Scheme, allowing millions of individual tourists to travel to Hong Kong and thus boosting tourism in the region. Beijing hoped that these two significant “gift packages” could stimulate Hong Kong’s economy—which at that time had just been hit hard by SARS—and make the Hong Kong people more “patriotic.” For a while, the results looked quite promising for Beijing—following the 2008 Beijing Olympics, 51.9% of Hong Kong residents identified as either “Chinese” or “Chinese in Hong Kong,” a historic high since 1997.

It was under these circumstances that Beijing began to feel confident that opening full democracy to the Hong Kong people, as promised in the Basic Law, would not turn Hong Kong into an intractable rebel. In 2007, the NPCSC in Beijing dictated that Hong Kong would be able to directly elect its Chief Executive beginning in 2017. The reform plan, however, foundered in 2015 due to irreconcilable differences between Beijing and the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong over the qualifications required for electoral candidates. Beijing was upset by the fierce resistance against what it considered a signal of goodwill. Another major policy shift was underway.

The third phase (2014-2020) started with a white paper published by the State Council, the central government of China, in 2014, during the height of debates around universal suffrage in Hong Kong. In the white paper, Beijing affirmed its “overall jurisdiction” over Hong Kong. In the following years, this assertive turn was followed by the disqualification of opposition lawmakers, the tightening of election candidacy, and more controversial laws, the most controversial one being the Extradition Bill that triggered massive social unrest beginning in 2019. Impatient with the prolonged turmoil, Beijing now wants to solve the problem, once and for all.

National Security Law and a New Era of Hong Kong

In June 2020, the NPCSC instituted its own Hong Kong national security law from above by appending it in Annex III of the Basic Law. While Beijing has used this method before to apply national laws in Hong Kong, this was the first time that it imposed a national law with substantive criminal charges. This law establishes a new national security committee—whose decisions are exempt from judicial review—inside the HKSAR Government. The law also mandates that the Central People’s Government create a national security office in Hong Kong that can take over certain cases and exercise jurisdiction.

The national security law and the electoral reform together mark a new era of Beijing’s policy towards Hong Kong: the space for the opposition camp is significantly limited, and pan-democracy activists can be more easily charged with much more severe punishment. Opposition politicians and lawyers fear that the national security law will override the existing common law system in Hong Kong and compromise the city’s judicial independence, while Beijing claims that it will only intervene in extreme cases and that Hong Kong will be better served by stability that results from the national security law. So far, dozens of political activists have been prosecuted under the law. The court seems to struggle to find a balance between maintaining its independence and not angering Beijing, which can easily reform the judiciary if it wants.

Suppressing opposition in Hong Kong is not the only task Beijing wants to achieve—it also needs to cultivate a team of reliable administrators that it can trust. Just before the NPC session in early March, Tian Feilong, a mainland-based law professor affiliated with the semi-official Chinese Association of Hong Kong & Macao Studies, wrote an op-ed titled “The Rebirth of Democracy in Hong Kong,” in which he argued that Beijing needs “capable patriots” rather than “loyal garbage.” Similarly, Zheng Yongnian, a professor who advises President Xi on Hong Kong, said in an interview that there are people who “pretend to be loyal” but have no “ability to solve problems.” If Beijing wants to demonstrate that Hong Kong can succeed without an opposition in this new era, it must first prove it can govern well.

By taking such an assertive stance towards Hong Kong, Beijing is placing a bet. Internationally, it is now facing mounting pressure and engaging in tit-for-tat sanctions with major Western countries. Domestically, though, Beijing is also overdrafting its legitimacy in Hong Kong upfront—being tough and paternalistic at first and hoping that things can end up well in hindsight. Whether or not this gamble pays off will only be revealed with the passage of time.

Featured image source: Anthony Wallace/AFP — GETTY IMAGES

Comments are closed.