Back in the 60s, the pharmaceutical company G.D. Searle helped to develop the first hormonal contraceptive, Enovid, amidst a climate of scientific hesitance. While the complexities of reproductive physiology provided significant challenges to the conception of “the pill”, the Catholic Church, popular resentment and widespread cultural conservatism arguably provided a greater hurdle to the drug’s inception. For fear of these political and religious forces, G.D. Searle actually took the backseat in a few stages of the drug’s development by, for instance, outsourcing some testing to Gregory Pincus, who was conducting research for Margaret Sanger at the time. In fact, the drug was not even primarily marketed as a contraceptive initially, despite Searle’s knowledge of its ability to act as an anti-ovulate.

Gregory Pincus reviewing notes in the lab, Source: PBS

Gregory Pincus reviewing notes in the lab, Source: PBS

Beneath science’s intricacies, social factors and the political pushes of the day-to-day exert significant influences on the direction that research takes, who it is targeted for and whether or not we should be doing it at all in the first place. Throw in the added ethical implications of altering human cells—whether or not it be related to reproductive health—and the finicky nature of the subject can create a hotbed for discussion and ultimately the stagnation of scientific advancement (for better or worse). Still, this begs the question, when it comes to this research, why do we feel comfortable experimenting on and afflicting certain demographics and not others? With regards to reproductive interventions, specifically, the burden quite clearly falls on females, be it physically, mentally or financially—but this may be starting to change.

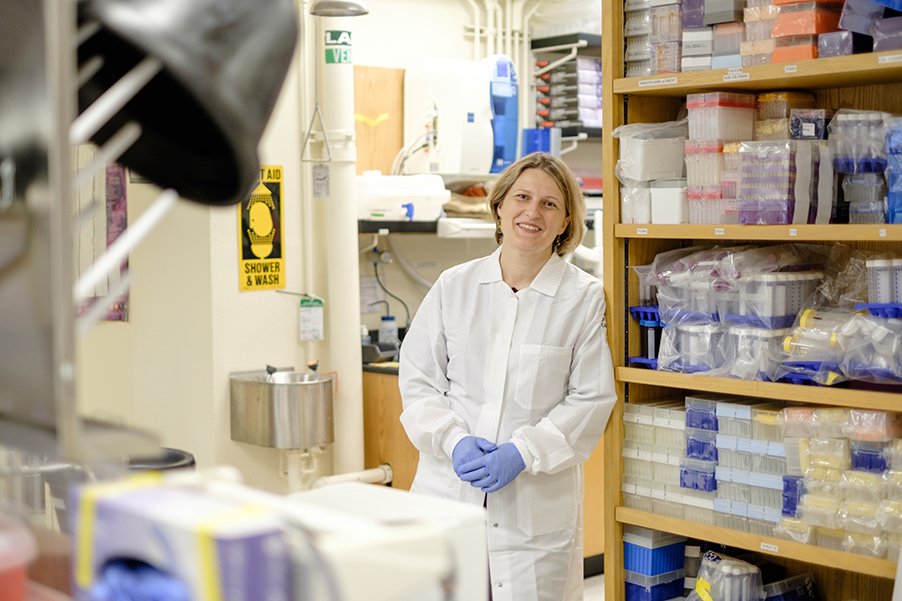

In the 1500s, an Italian scientist named Gabriele Fallopio developed the first male contraceptive, the linen condom. While some significant advancements were made in the time since then, in recent years, scientific groups across the world have been looking into innovative methods for providing contraceptive solutions to males, and others targeted for females that are non-hormonal. While current contraceptive methods are often either mechanically or chemically invasive and mostly available for females alone, Polina Lishko, an Associate Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and her group are conducting research that may lead to the development of non-hormonal contraceptives that can circumvent these risks. Dr. Lishko recently received a MacArthur Fellowship (and the $625,000 grant that comes with it) for her work in this area of reproductive physiology. Furthermore, her group’s discoveries might also lead to the development of non-hormonal male or unisex contraceptives, shifting the financial and physical burden of birth control.

Dr. Polina Lishko in the Lab, Source: MacArthur Foundation

Dr. Polina Lishko in the Lab, Source: MacArthur Foundation

Will Skinner, a graduate student in the lab who is leading the project on unisex contraception, elaborated in an interview for the Berkeley Political Review that the goal of the research is to develop “novel, non-hormonal, unisex contraceptives.” Without getting technical, “unisex, in this case, means contraceptives that could theoretically be taken in anyone’s body. And the only way to do that is to target sperm cells because sperm cells are the only cells in the body that are generated in one person’s body and fulfill their role in another.” This effort to develop unisex contraceptives can take shape through different strategies depending on the focus and expertise of the research group. Skinner explains that these sperm-specific targets “fall into two categories; one is interfering with the production of sperm. It’s called spermatogenesis, happens in the testes, and there have been many attempts to do this. And some of them may be quite successful. But, the current, farthest along products are hormonal male birth controls.” As he explains, this type of intervention involves a three month lag (both for starting and stopping treatment) and incites hormonal side effects. This is where his research comes in:

The other side of things would be by targeting mature sperm (so any drugs that affect sperm after they leave the testes)… once they leave the testes, there’s still this long process of maturation that needs to happen before they’re ready to fertilize the egg. Part of that happens in the male reproductive tract, in the epididymis, and part of it happens in the female reproductive tract. So, if we can target proteins or processes that occur in those mature sperm, the effects can be immediate, and it can be applied either in the male or female body, and it’s outside of the testes, which makes drug delivery easier. And so that’s sort of where our lab has focused, [as have] many other organizations…

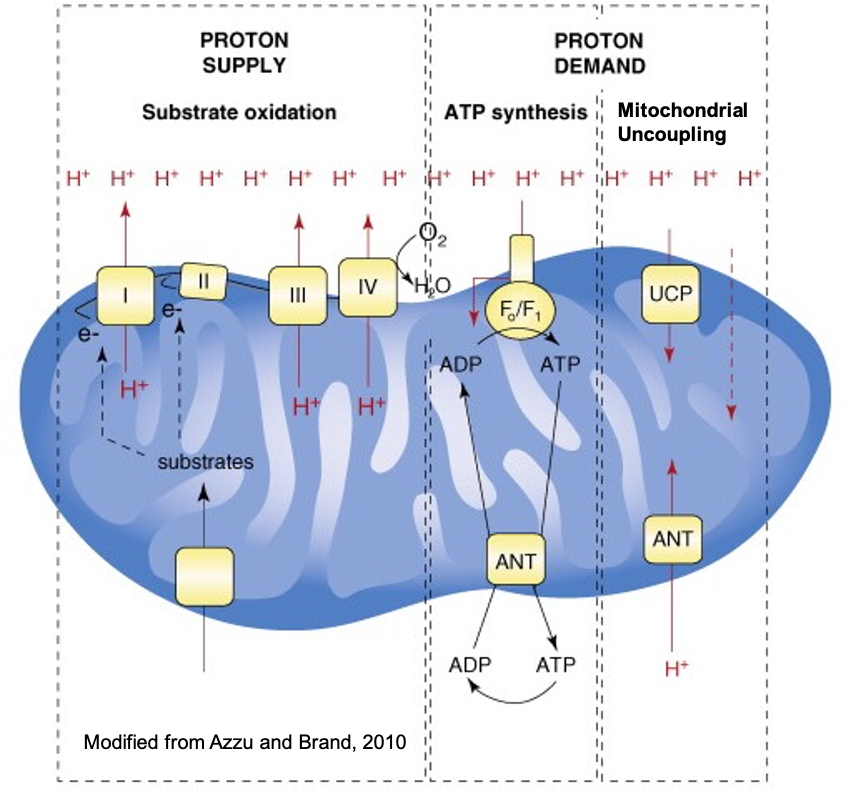

Because of where the lab’s expertise resides and due to the potential of mitochondria—an organelle that acts as the “powerhouse of the cell,” as most people remember it from high school biology—as a target for contraceptive therapies, the lab focuses a lot on mitochondria. Mitochondria’s central role in many physiological processes involving sperm maturation and motility, makes it such that interfering with mitochondria, and thus these processes, introduces significant opportunities for contraceptive research. The Lishko Lab has specifically narrowed their focus onto an ANT (Adenosine Nucleotide Transporter) Protein known as ANT4 (located in the mitochondria), which helps to mediate a process known as mitochondrial uncoupling. By activating mitochondrial uncoupling via ANT4, sperm cells slow ATP synthesis, thereby draining the sperm cells of energy and inhibiting fertilization. Furthermore, ANT4 is only expressed in sperm cells, thereby making it a strong pharmacological target. The lab also has several other projects in the works.

Illustration of mitochondrial uncoupling; ANT proteins channel H+ ions back into the mitochondrial matrix (interior) without generating ATP—a molecule utilized by cells for energy, Source: Berkeley Lishko Lab

Illustration of mitochondrial uncoupling; ANT proteins channel H+ ions back into the mitochondrial matrix (interior) without generating ATP—a molecule utilized by cells for energy, Source: Berkeley Lishko Lab

When asked whether scientific hurdles or social forces are the primary reason that there are so few unisex and male contraceptives on the market, Skinner says “It’s definitely both. You’ll see a lot of BuzzFeed style articles that like to just place the blame [on companies and social issues]…there’s a kernel of truth in [some of these articles], but it’s not that simple….There are both very challenging scientific problems, and a lack of funding, and a lack of interest that has led to little progress being made on these challenging problems.”

To touch on some of the other attempts at developing male/unisex contraception, a 2008 study by CONRAD, a nonprofit conducting research on reproductive health, which focused on hormonal male contraception, was ultimately abandoned in 2011 because of the side effects that some men in the study experienced. Furthermore, Bayer, a pharmaceutical giant, scrapped one of their projects on male contraception in 2007— they doubted men would care to accept responsibility for contraception, according to some sources. As Skinner explained, this doesn’t tell the whole story, but it does represent a trend that has held back the development of male and unisex contraception.

Large Pharmaceutical companies have taken a step back from developing male/unisex contraceptives in recent years. Shown above is Bayer AG in Leverkusen, Germany, Source: Bayer

Large Pharmaceutical companies have taken a step back from developing male/unisex contraceptives in recent years. Shown above is Bayer AG in Leverkusen, Germany, Source: Bayer

When examining the biochemical complications of male/unisex contraception, there are a variety of processes and physiological facts that impede progress. For example, testosterone breaks down much faster in the bloodstream than progesterone and estrogen do, meaning, in some treatments, males would need to take pills or injections multiple times in a day, while current female, hormonal contraceptives require doses daily or even less frequently. Moreover, males often lack a clear physiological readout as to whether or not their treatment was successful. Furthermore, as Skinner explains, many boxes need to be ticked off to get a drug approved: “specificity of action, potency of action, non-toxicity of action, deliverability, shelf life stability, and dozens of factors like that, and any one of those can sink a ship… Lots of great ideas have one fatal flaw.” Furthermore, human sperm cells are somewhat less studied than other cells in the body, and they vary to a significant extent compared with sperm cells of other species, such as mice, which can often be utilized in the drug development process.

On the other hand, when looking at the social forces shaping this scientific progress, Skinner explains that “There’s this idea floating around in the world that [male/unisex contraception] is not worth the investment because men wouldn’t take it, or men would not be reliable to take it, or no one would trust men to take it.” This isn’t the case according to him:

People’s expectations of their roles and responsibility in the reproductive process are shifting. If there was ever a generation that could stand up and demand that this become real, it is ours. And, no one is ever saying that this should replace female contraception or everyone should rely on men to take it, or that all men would take it, but when our denominator is three and a half billion people, if five percent or ten percent of those people take it, that’s millions of people and possibly millions of unintended pregnancies avoided.

Unwanted pregnancies are a major public health issue and lead to many discouraging life and health outcomes. Even conservative estimates show that these unwanted pregnancies lead to decreased educational attainment, increased household stress, and decreased participation in the labor force among other negative implications. Furthermore, a study by the World Health Organization (WHO) has shown that they also lead to higher rates of poverty and increased infant mortality. As such, the work of research groups such as that of Dr. Lishko’s should be coupled with strong support outside of the scientific community.

One interesting aspect of this intersection between social and scientific forces plays itself out in its relation to the FDA. The public is likely becoming more cognizant of the FDA’s role in drug approval and regulation due to the press surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine approval process. According to Skinner, new kinds of compounds and therapies face a much higher burden of proof with the FDA: “It’s just like movies; movie sequels in the same franchise are easier to get made than making something new.”

Unlike the movies, however, treatments bring about widespread, significant risks, which need to be considered (by the FDA) in a more comprehensive manner than a Bond stunt per se. Skinner elucidated in the interview that “With the FDA, the benefit of the drug always has to be weighed against the risks that it is treating or avoiding.” While this can slow the drug development process, it is extremely important because it prevents ethical violations and medical disasters. Because female contraceptives were developed in the ‘60s, a time when these regulations were looser, they were easier to bring to the market. Male contraceptives, however, are emerging in a time of greater regulation and rigorous oversight, as Skinner explained, and they deal with an interesting conception of what “risk” actually means and who is involved. He elaborated that:

In the case of unisex or male-delivered contraception, males bear almost no personal physical risk of getting someone else pregnant, and the FDA does not really have a historical precedent for how you weigh side effects in the patient taking the drug against the physical risks that would be incurred by their partner. It’s just interesting; there have been papers written and analysis done to try to build a new framework for how you would weigh those, but it’s tricky. And, a lot of the reasons the market would want a drug like this is actually not necessarily for physical risk, but for economic risk, social risk, all of the many other reasons people might not want to have a child at that time. The FDA really does not have a history of accounting for those sorts of things. They are all about physical risk.

Furthermore, because these drugs would primarily be taken by healthy individuals (meaning there would be little risk of nontreatment) for prolonged periods of time, the drugs must be extremely safe and effective to clear the FDA.

Enovid, Source: PBS

Lastly, there are also some bizarre reasons for why these types of drugs haven’t yet been approved. “There is a very effective male contraceptive that works by inhibiting a pathway called the retinoic acid biosynthesis pathway,” Skinner told me. “It works great, was discovered in the ‘60s or ‘70s (a while ago), well-tolerated except that it also inhibits the enzyme that breaks down alcohol. And, if you drink alcohol while taking this, you get violently ill… That scuttled that right there.”

Big Pharma has also directed funding and resources away from the field. Given that pharmaceutical companies often employ a cost-benefit analysis that is significantly different from what is used by non-profits or academic groups, most of the research surrounding male and unisex contraceptives has been left to research groups like Dr. Lishko’s. Skinner explained that:

There was some concerted effort by big pharmaceuticals around the turn of the new millennium. By 2009, it had all completely ceased… With those players out of the space, progress just slows, and so it’s left to academic labs like us to try to pioneer the ideas, and it’s left to small nonprofits like the Male Contraceptive Initiative… or governmental funding… the big one that funds a lot of our work and work in the field is the NICHD (National Institutes of Child and Health Development), but that amount of money is just smaller… There’s lots of people, and when I say lots I mean dozens to hundreds of people like me and people like Polina who are trying to push this field forward, and we can get a compound to preclinical levels, and maybe with a big grant could get it to phase one, and that’s really where pharmaceutical companies might start to take interest.

As far as government policy and intervention goes, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has led to an increase in the availability of contraception for women, thereby reducing financial and other challenges. However, it explicitly denies coverage for male contraception, quite clearly placing the burden on women. According to HealthCare.gov, all plans in the health insurance marketplace “aren’t required to cover drugs to induce abortions and services for male reproductive capacity, like vasectomies.” Blurring this line of what qualifies as male versus female contraception may lead to an interesting shift in policy and access to our funding for certain contraceptive options. Furthermore, options for male contraception are somewhat poorly developed (although progress is being made), and so the number of men who take the initiative on contraception could be improved—For instance, only about 13 percent of reproductive age, married men have received a vasectomy.

Skinner explains that “We need more money in the space, more enthusiasm, and that’s starting to come in a grassroots way.” Unfortunately, we might still be years away from the novel products that groups like the Lishko Lab are developing. “Despite overhyped news article to the contrary, there will not be a viable male or unisex contraceptive on the market within …3-5 years, and … all of this non-hormonal stuff, is probably more like 10 years [away]. In that interim, there are a lot of people with unmet needs right now. The way we address those unmet needs is through access and equity and empowerment”

This lack of progress around male, and unisex contraception, and the issues of hormonal birth control, can lead to quite negative effects, as previously discussed. Around half of all pregnancies are unintended. While this does not mean that all of these are unwanted, those that are negatively impact life and health outcomes for women and their children. Skinner concluded that “It sometimes feels like we are pursuing this project of passion, which in the broader funding world, is not always supportive or doesn’t always get it.” It is incredibly important though. By improving options for females, making them affordable and accessible, and providing the tools for males to become equal partners in the quest for safe and effective contraception, reproductive health and equity may just take a giant leap forward.

Featured Image Source: PBS

Comments are closed.