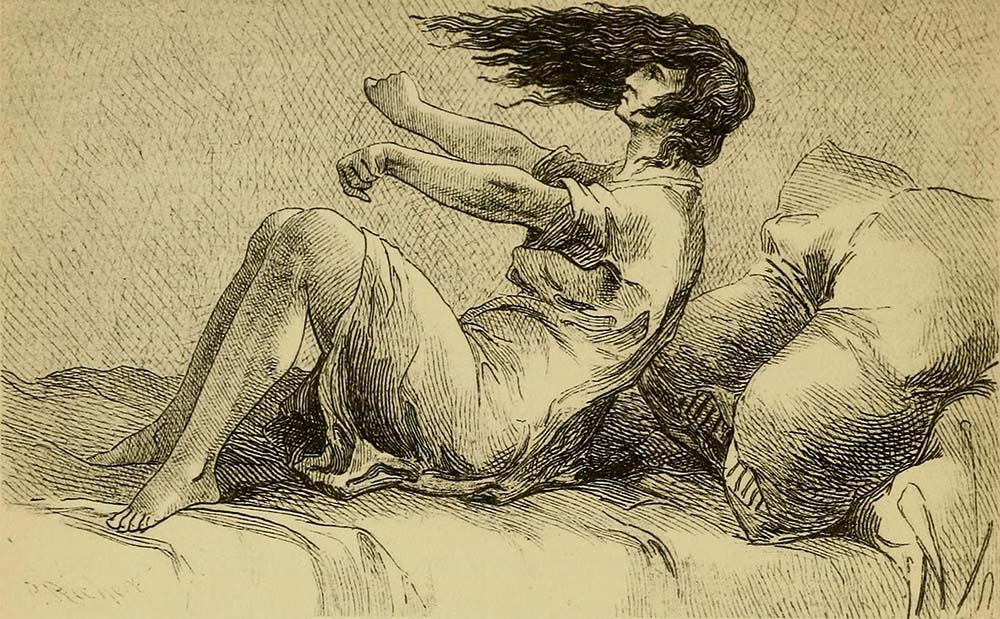

Human history can be defined by many threads, one being the millennia spent oppressing women’s bodies, minds and spirits. This has lasted and thrived into the modern era, resulting in unfounded beliefs about female frailty shaping every facet of our society. The stereotype that women are weak, fragile and to be protected from strenuous mental and physical activity due to their incompetence has persisted. In western cultures, where this belief system is particularly strong, its influence has bred such phenomena as female hysteria. Female hysteria’s definition is difficult to summarize because its “symptoms were synonymous with normal functioning female sexuality.” 18th-century French physicians essentially classified it as “something akin to emotional instability.” However, female hysteria’s inception dates back to the ancient Greek theory of the wandering womb. The wandering womb was a way to explain anything in a woman’s behavior or physical state that men deemed difficult or unappealing. Well into the 19th century, “treatment” for female hysteria could even land women in mental institutions. The (male) medical community’s interest in female hysteria continued into the early 20th century when doctors deemed the “rest cure” a viable treatment. To administer this “cure,” men would force a woman to remain bedridden, away from all physical or mental activity for as long as her husband, father, or brother saw fit, which certainly created psychological distress if it was not already present. Charlotte Perkins Gilman famously wrote the eerie and unhinged horror story “The Yellow Wallpaper” after being treated with the rest cure, about a woman who went insane and began seeing and hearing tormented women within the wallpaper of the room she was imprisoned in.

When considering the historical medical treatment of women the exact science, or lack thereof, behind female hysteria diagnosis is not as important as the social conditions that allowed it to take place. Doctors only removed female hysteria from official medical texts in the 1950s; for centuries upon centuries before that, men considered women’s health issues mysterious, inconvenient, and a direct result of their being female. The perception of femininity was deeply entangled with hysteria. When misinformation spurred by the toxicity of the patriarchy has run rampant for so much of human history, social consciousness does not change overnight, over a few years, or even over decades. This misinformation has created a dangerous environment in medicine that is alive and well today in which women’s health issues are dismissed, underestimated and misdiagnosed due to a lack of widespread education on female bodies. This inadequate treatment is amplified when race, class, body size and age are factored in as points of discrimination.

It’s All In Your Head

Countless women know first-hand that doctors take their pain less seriously than men’s: according to a survey of women with chronic pain, 83 percent reported that they had experienced gendered discrimination while seeking treatment. Women are significantly more likely to be told “their pain is “psychosomatic” or “influenced by emotional distress,” a finding that is disturbingly reminiscent of a female hysteria diagnosis. Women are also more easily dismissed because their health concerns are chalked up to symptoms of menstruation. This treatment discrepancy is only worsened when women do suffer from a menstrual-related chronic illness such as endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome or fibroids. Amy M. Miller, president and CEO of the Society for Women’s Health Research, has stated that in these cases and in others, “it is common… to be told their pain is just a normal part of being a woman.” These kinds of experiences are incredibly invalidating and often force women to seek out multiple specialists before being properly diagnosed, not because their ailment is particularly rare or difficult to catch, but because doctors dismiss them before those diagnoses can even be considered.

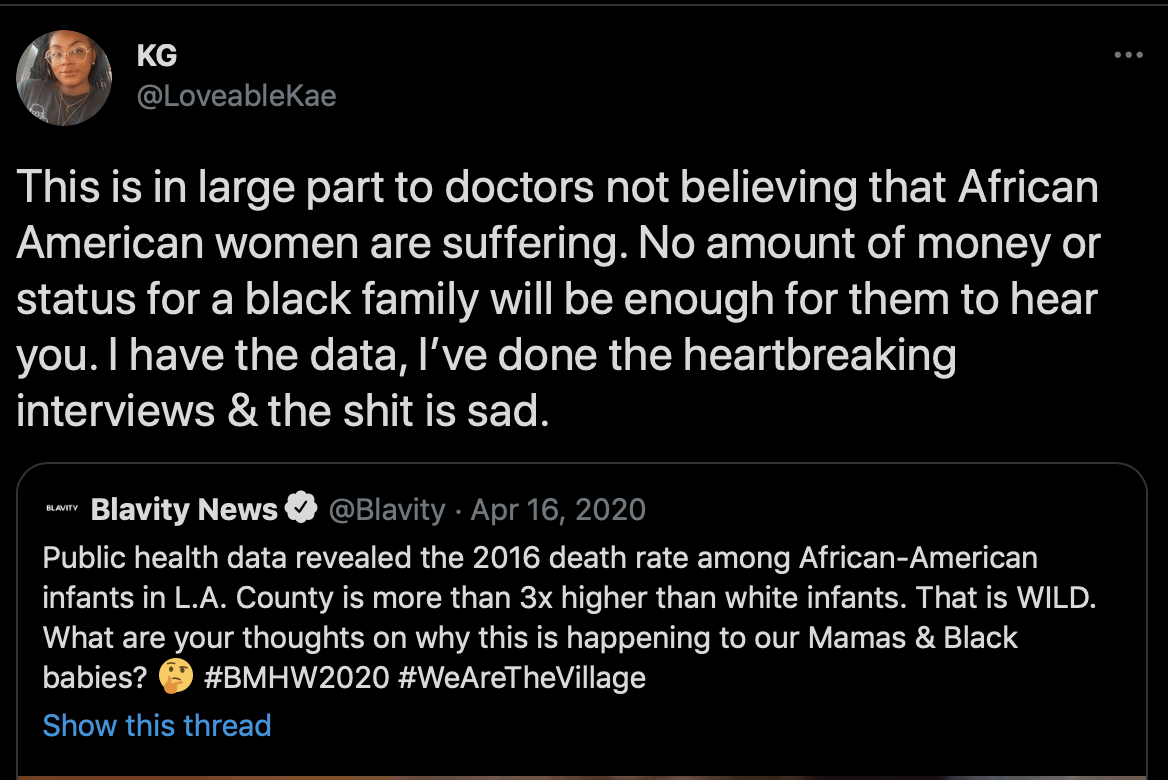

This kind of oversight can also be life-threatening. A study carried out by Yale Cardiology found that “many women hesitated to seek help for a heart attack because they worried about being thought of as hypochondriacs.” Overall, medical professionals do not take women’s – particularly women of color – symptoms seriously, showing a consistent lack of care for women’s health and recovery if treatment will take more than a cursory effort. Gabrielle Jackson, the author of a book on this topic, asserts that “women wait longer for pain medication than men, wait longer to be diagnosed with cancer, are more likely to have their physical symptoms ascribed to mental health issues, are more likely to have their heart disease misdiagnosed or to become disabled after a stroke and are more likely to suffer illnesses ignored or denied by the medical profession.” Even when prescribed medication after a diagnosis, “for decades, [into the 1990s] women were excluded from clinical drug trials based, in part, on unfounded concerns that female hormone fluctuations render women difficult to study.” And, “while the inclusion of females in drug trials has increased in recent years, many of these newer studies still fail to analyze the data for sex differences.” This list of inequities is disheartening to hear, and even more disheartening for the countless women whose lives are derailed by the discriminatory failures of medical professionals.

Taking One For The Team

Birth control is a prime example of the disparity in the medical treatment of women versus men. Medical professionals treat women as both expendable and superhuman in the birth control debate; societal norms expect women to carry the bulk of the responsibility in avoiding pregnancy. While female birth control is very common, it brings the risk of inconvenient and even dangerous side effects. The known and accepted side effects that women suffer include but are not limited to nausea, weight gain, mood changes, depression, changes in sex drive, and blood clots. Meanwhile, a promising study by the WHO on hormonal male birth control options such as a long-lasting injection was “stopped early due to side effect concerns, particularly related to concerns about negative effects on mood.” The Endocrine Society’s Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism also “reported a high success rate during a clinical trial of an injectable contraceptive for men,” yet after three years they discontinued the study and dismissed talks of putting male birth control on the market due to what they called “serious side effects, such as depression and mood disorders reported by those involved in the study.” Understandably, this was a controversial decision seeing as women’s birth control led to around 40 percent of users developing or experiencing worsened depression after 6 months, yet those same products have been on the market and pushed on women since the 1960s. In other words, promising studies were discontinued and never able to move on to FDA approval because men were suffering in the same way that women do constantly for the sake of birth control.

Those against investing in male birth control often argue that women should be primarily responsible because it is their bodies that will be affected by birth control failure, while men can feel satisfied with their use of a condom or “the pull-out method” despite the heightened risk. However, given that a man can potentially impregnate someone every time he has sex while a woman’s likelihood of becoming pregnant changes over the course of her hormone cycle, it is a far greater aversion of risk to debilitate the man’s reproduction. Granted, because of this difference in hormonal cycles it is difficult to safely subdue sperm to an acceptable level of efficacy in preventing pregnancy. There are concerns that men’s sperm count and strength would be directly affected by hormonal birth control. According to a study recounting these trials, “Nonhormonal contraception may be more appealing to men than hormonal approaches currently in development as it would avoid any impact on testosterone concentrations and, hence, sexual function, muscle or bone mass, or sex drive.” Still, this implies that regulators are highly concerned with marketing appeal and social stigmas around testosterone as opposed to serious health issues. The fact that scientists are not able to or willing to move forward with experimentation on men once they observe adverse side effects, while women’s birth control is essentially a decades-long experiment in hormonal manipulation, shows a fundamental, systemic difference in the scientific attitude towards women’s lives and bodies.

Real Women, Real Lives

In addition to disease/death statistics and the birth control debate, anecdotal evidence is especially important in exposing the way women are treated in healthcare because it is something that so many people have experienced on an individual level but is not often discussed as a larger, consistent problem. Social media and access to the internet have been powerful tools for connecting women’s medical horror stories. So many of these stories relay years of undiagnosed pain because doctors didn’t believe them. In an article consisting of various women’s experiences with being dismissed when seeking treatment, one woman shared that “I have chronic pain in my legs that sometimes limits my ability to walk […] One time […] I went to the doctor for help and she offered – in all seriousness – to escort me to the psych ward.” Another woman who had an E. Coli infection was told by the urgent care doctor that she was probably just cramping from menstruation and “advised [her] to take some ibuprofen and “sleep it off.”’ These kinds of stories are not as impactful individually, but together they paint a disturbing picture of malpractice against women. When the specific commonalities of being thought of as liars, exaggerators, and being incapable of understanding their own bodies are brought to light, the direct effect of female hysteria’s long, brutal reign is clear.

It is extremely important to acknowledge again that intersectional prejudice bleeds into medical discrimination as it does every part of society; BIPOC women, trans women, and disabled women are at a heightened risk of suffering unnecessarily, losing bodily autonomy, or even dying due to the systemic issues of the medical field and especially due to individual hostility on the part of the medical professional. Women, especially marginalized women, deserve our attention and our protection within the systems that pledge to heal, not harm. We have come a long way since the Greeks considered the “wandering womb” a credible scientific theory, and since men could imprison their wives as a part of the “rest cure.” But each new iteration of society since then has built on those beliefs; we have never let go of the warping influence of the patriarchy, and every day, women all around us suffer physically and mentally because of it.

Featured Image Source: Hysteria and Allied Conditions

Comments are closed.