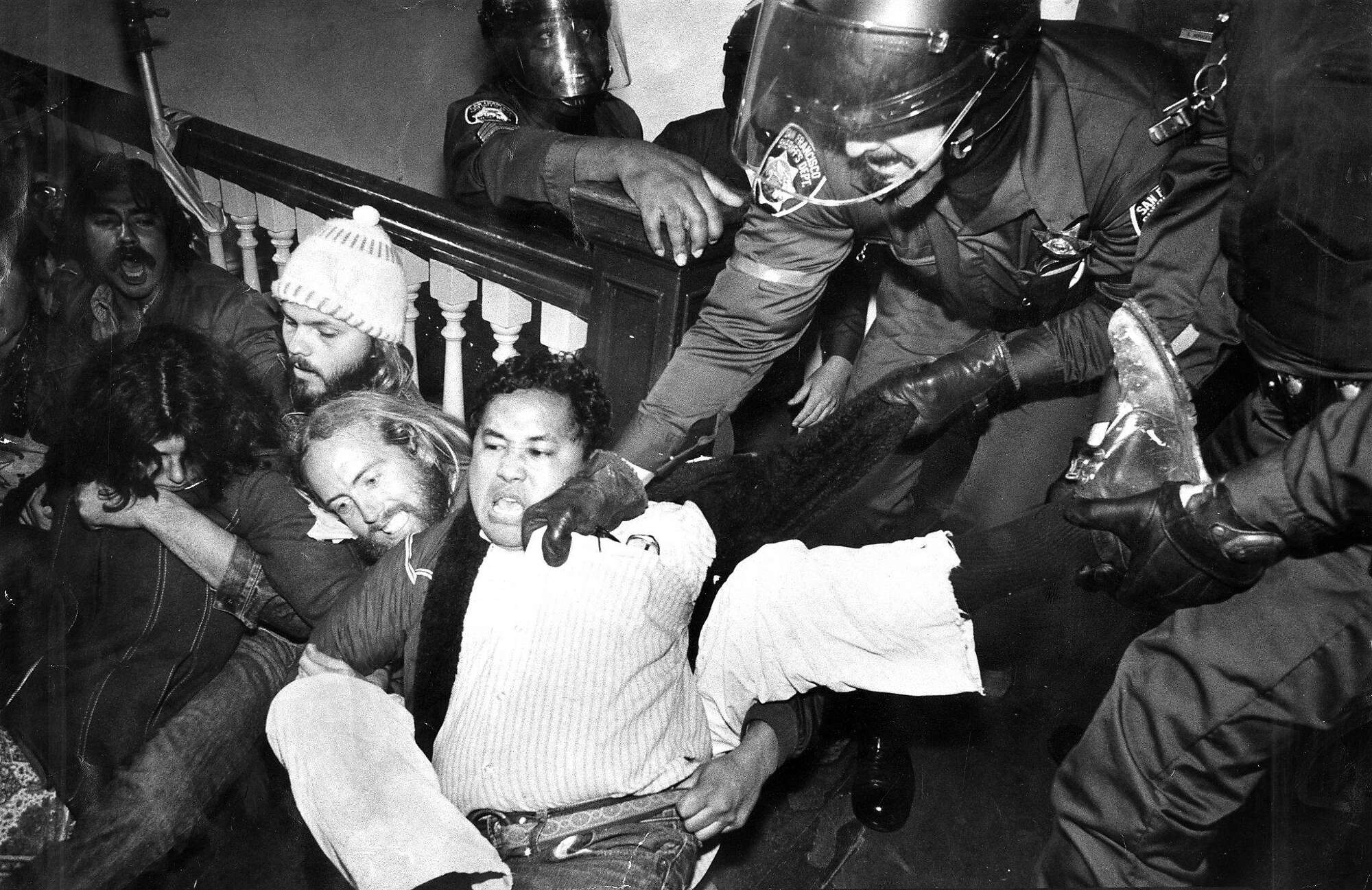

Manilatown was supposed to be an asylum for Filipino men immigrating into San Francisco in the ‘20s and ‘30s. It wasn’t formed by resident choice, however, but rather necessitated by neglect and violence — beatings of Asian immigrants, redlining, and broader trends toward gentrification ultimately forced these Filipino immigrants into Manilatown where they managed to build community and (some) stability in the face of alienation and discrimination. Regardless, in 1977, the images of Manilatown circulating the press were not exactly representative of the promise associated with these Filipino immigrants trying to achieve the American Dream. Instead, activists and residents of the International Hotel in Manilatown were beaten by police, and residents forcibly evicted, with the building facing its own destructive fate in 1981. The tearing down of the I-Hotel was far from an isolated incident, but rather part of broader government programs known as redlining and urban renewal (i.e. systematized gentrification and displacement) whereby the entire country witnessed this mass displacement and disinvestment under not-so-subtle racial context — take, for example, Boston’s West End in the ‘50s, or Milwaukee’s Midtown in the ‘60s. Many communities today face similar challenges of their own and still struggle from the effects of these racist policies from decades prior.

However these practices were targeted by certain progressive policies, introduced in the ‘60s and ‘70s, with the intention of combating concentrated poverty and racist housing practices, with one notable piece of such legislation being the Community Reinvestment Act, or CRA, created in the same year as the destruction of the I-Hotel. Why then, 44 years later, is this relevant now?

With the current presidential administration promising to enact progressive changes to the structure of the housing market, corrections to racial disparities, and a balancing of the demographics of poverty, the field of community development, or CD, has found itself in a dynamic and empowered condition. However, while affordable housing and the birth of small businesses in low- to moderate- income communities — major focuses of CD — all sound nice and will continue to be some of the many types of projects of CD, these projects often require abundant capital that unfortunately is very hard to find. As such, the country is facing a housing crisis and many communities have found themselves with limited access to the resources and institutions that others take for granted (such as strong educational systems and access to healthy foods). In fact, according to a study conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “an estimated 2.1 million households, or 1.8 percent of all households, are in low-income and low access census tracts and are far from a supermarket and do not have a vehicle.” So, conservatively, one out of every fifty people in the US has limited access to even the most basic of needs, not to mention the millions of others who don’t have healthy housing, living wages, and sufficient healthcare. To try to compile all the statistics of this sort would be exhausting with each disparity building off of the last and all being rooted in a common, inequitable foundation.

This is where the Community Reinvestment Act, or CRA, comes in. Since its inception in 1977, the Community Reinvestment Act has come to be the most significant source of capital for community development projects above all other funding sources be it direct government funding, philanthropic grants, or private investments. However, CRA is not an infinite well, full of capital for developers hoping to build supermarkets in food deserts or construct affordable housing units. Rather, it works as a regulatory stick, keeping banks in check and “ensuring” that they equitably invest in communities within their assessment areas.

This very concept of assessment areas is actually one of the most contentious areas of the present-day CRA. The way that CRA currently works is that banks are evaluated on a curve – if banks in a neighborhood score well on their CRA assessments by making good lends to low- to-moderate-income, or LMI, communities and individuals, then all others in the assessment area are held to a higher standard. While this is advantageous for communities located in financial centers like San Francisco, neighborhoods in communities without an abundance of banks are left high and dry, since there’s little to no competition on the CRA curve.

According to Carolina Reid, Associate Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of California at Berkeley and Faculty Research Advisor for the Terner Center for Housing Innovation, “there are some key areas of debate [around CRA]…one is this question of assessment areas…Should banks only get credit for things that they do within their assessment area, or should we make assessment areas broader, or should banks get CRA credit for lending to LMI communities no matter where they are?” Compounded with a shift in poverty towards the suburbs and rural communities where these financial institutions tend to be few and far between, this competitive aspect of CRA can be quite problematic. This, Reid further explains, is “ a question that we really need to grapple with when we think about the sort of suburbanization of poverty, changing pressures around gentrification, and the fact that banks are unevenly distributed, so there’s all these places in the country that don’t get any CRA dollars at all.” With the curve set to zero, banks in these impoverished communities have extra freedom to act in an exclusionary manner and to continue a century old tradition of discriminatory lending practices.

Furthermore, CRA currently does not mention anything about race — ironic for a policy designed to combat the racist housing practices that impacted communities like Manilatown in the past and continue to harm communities of color today. As such, banks can make loans that qualify for CRA credit without actually fixing the structural inequalities that have led to disinvestment in communities of color. In fact, according to an Economic Innovation Group report, “Hispanics are four times as likely as whites to live in a high-poverty neighborhood and Blacks nearly six times.” This is certainly not a coincidence. Instead, it is reflective of past unfair practices and indicative of a need for significant change.

Reid also emphasized that banks should not get credit for lending to high income borrowers in LMI neighborhoods — something that is allowed under the current edition of CRA. Furthermore, increased attention should be paid to the types of businesses that are eligible to receive CRA funding (e.g. are they paying living wage jobs?).

However, CRA has many successes which makes it worthwhile to focus on and strengthen. As Reid points out, the “biggest success of CRA is the fact that it has helped to grow a really rich community development ecosystem … We have become so much more sophisticated and powerful in terms of doing community development work because banks have supported and put money into organizations that are doing this work.” What Reid is alluding to is the fact that CRA has forced an intricate network of CD organizations, such as intermediaries and Community Development Financial Institutions, to coalesce and maximize what can be done with limited capital by designing innovative projects such as community land trusts, mixed income housing, and other niche residential and commercial complexes.

Take for instance the Rolland Curtis Gardens in the Exposition Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, a $71.9 million dollar project which leveraged CRA dollars to convert a tired affordable housing structure, that was about to be purchased by a developer looking to convert the units into USC student housing into a modern complex, with triple the number of affordable units and a community health clinic. Furthermore, banks provide CD organizations across the country, like CDFIs, with the capital to kickstart a wide range of projects from grocery stores to small businesses or even community centers in LMI neighborhoods just to touch on a few. Specifically, however, as Reid points out, it is best with real estate deals such as the Rolland Curtis Gardens. However, even projects such as these that may seem great at the surface struggle with issues such as resident retention and gentrification. Just because a project provides replacement housing for residents — something that the destruction of the I-Hotel purposefully avoided as did other urban renewal projects — does not mean that residents will benefit.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55561909/Screen_Shot_2017_07_03_at_2.03.36_PM.0.jpg)

Despite all its flaws, CRA is the primary mechanism for LMI communities and individuals to acquire capital. However, Joseph Otting, a Trump Administration official, attempted to cripple CRA in May of this past year — one week before resigning, leaving many communities in jeopardy of losing this critical source of funding which can be leveraged for access to basic needs. The way that CRA is structured is that banks are primarily regulated by one of three regulatory agencies — including the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, or OCC. Joseph Otting, as the Comptroller of the Currency during Trump’s presidency, relaxed CRA requirements — that is beyond their former, tolerant state, allowing for some banks to be almost exempt from fair lending practices and causing confusion among the other two regulatory agencies outside of the OCC. As such, CRA is scrambling to piece itself together amidst the acts of this saboteur, not to mention a public health crisis and its own weak language.

Regardless, even though this piece of legislation has been scraping by for the past half-century and has a history of mediocrity, CRA has actually gone through a couple periods of significant revision. Most notably, it received a bit of an overhaul under the Clinton Administration, and is now much stronger than it was at its inception. Under Clinton, the very idea of assessment areas was introduced. Now, with the Biden Administration promising to correct (or at least start to correct) the abundance of inequities in the U.S., it is not unreasonable to expect to see another shift in the structure of CRA. Many areas of CRA are currently under scrutiny beyond assessment areas. It is important to note that this attention is not only due to Otting’s attempts to subvert CRA, but also due to a bipartisan consensus that many pieces of CRA are flawed and in need of a renovation.

Different institutions have come forward recently pushing for change with advocacy agencies being the primary driving force behind this enforcement and improvement of CRA in the absence of strong policy. So, looking to advocacy agencies is a good method to gauge where CRA is heading. One such advocacy group leading the charge is the Center for Responsible Lending, or CRL. In the middle of February, CRL, along with Community for Self-Help, a large CDFI headquartered in North Carolina, put out a document advocating for a series of changes to CRA. To get an idea of the type of reforms CRL is pushing for, the document specifically states that “extensive data indicates that banks are not meeting the credit needs of Black and brown families. To ameliorate these gaps, CRA exams could include performance measures assessing responsible lending, investing, branching and services to people of color and communities of color.”

They have, furthermore, in this document published recommendations on how to revise the structure of assessment areas. “Banks have an obligation to serve LMI communities and communities of color in all of the areas in which the bank engages in significant amount of business … not only in areas with branches,” according to the document.

So, actions and recommendations such as these (they had also suggested an 100-day agenda for the Biden Administration) have placed the Center for Responsible Lending as one of the main organizations leading the way in advocating for progressive changes to CRA. With these modifications, and the political volition to apply them, CRA will be better able to serve LMI communities and communities of color — and accordingly help to prevent the woes of Manilatown and the other urban renewal projects of the past century. Other advocacy institutions and groups are also taking a stake in the revision of CRA including Greenlining, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, and the California Reinvestment Coalition among others. With pressure being applied to the Biden administration by advocacy groups and a persistently growing need for action, the first 100 days of his presidency may serve as an indication of how far the policies of the next four years will go towards correcting the past one hundred years of targeted disinvestment — a lofty yet essential project which the revision of CRA may just kickstart.

Featured Image Source: BPR Design Team — Catherine Hsu

Comments are closed.