Gabby Petito’s parents declared her missing on September 11, 2021. Within nine days, the name Gabby Petito had become a buzzphrase for news outlets and social media users alike. On TikTok alone, “#GabbyPetito” amassed over 794 million views. This kind of coverage placed Gabby’s case on a global stage at an unfathomable speed, and by September 20, the authorities had found her body, and her ex-boyfriend—who many suspected of murdering her—was on the run, with rewards of up to 30,000 dollars for information on his whereabouts. During those nine days, millions of social media posts and thousands of articles were made that theorized about and reported on her disappearance, decried her alleged attacker and called for her to be brought home safely to her family. It was the kind of attention any loving parent would want their child’s case to receive if the unthinkable were to happen; the smallest consolation in the midst of emotional chaos may be that people are looking for them, people will recognize them and people are willing to put pressure on authorities to solve their disappearance.

The examples of so many cases like Gabby’s, compared to others in which that small consolation is taken away, dictate that the victim must be three very key things: young, female, and white. In 2004, the late American journalist Gwen Ifill dubbed this phenomenon “Missing White Woman Syndrome” (MWWS). This refers to the disparity between media coverage of missing person cases involving young white women or girls compared to women of color and women otherwise not fitting that description. In an empirical study on the intersection of race and gender as it pertains to media coverage of these cases, white women as subjects accounted for 49.74% of articles, with the next highest demographic being white men at 17.40%. There is some contention around the true numbers, both because so many cases go unreported and because different databases have different definitions of white. This is due to outdated classification systems as well as lack of nuance in representation—the FBI’s database labels Latinx people as white.

The existence of this “syndrome” that plagues the media is due to many factors: young women, specifically those 21 years old and younger, are kidnapped, trafficked and murdered at higher rates than other demographics; racism intersects with classism, so wealthier families have access to private investigators and more influence over local authorities; systemic racism is deeply rooted, and there continues to be widespread personal implicit and explicit racial bias. There is also a perpetuated view of young and often attractive women as “damsels in distress” who need protection from the world by men; in reality, the world from which they need protection from is the world of men. So, when these women go missing, the public is rapt by the horror and longs to be a part of her rescue. It is a testament to the social impressionability formed by the racist ideals of the United States and other countries built on colonization, patriarchy, and white supremacy that a crime involving a young, white, female victim will be more fascinating and garner more sympathy than those involving people not within that demographic.

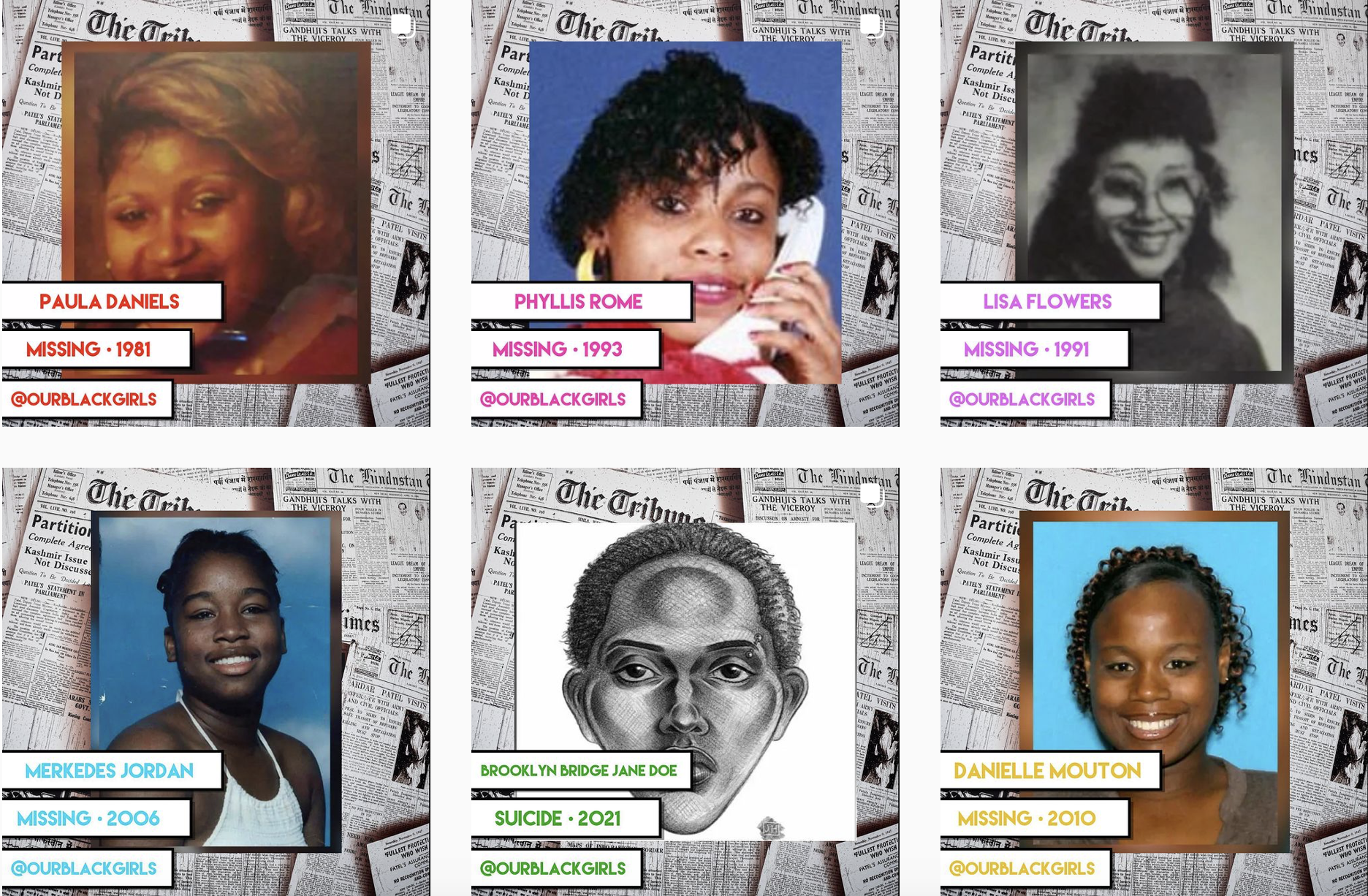

Missing White Women Syndrome exists in large part due to the media repeatedly and systemically failing to amplify stories of abuse inflicted upon other victims, especially women of color. Social justice movements like the website “Our Black Girls” and “No More Stolen Sisters” are evidence in and of themselves that marginalized communities are forced to rally around their vulnerable members and dedicate entire movements just to receive the same amount of public and legal attention as young white women like Gabby Petito.

“No More Stolen Sisters” is the catchphrase of the movement created in retaliation to the staggering number of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), a phenomenon that unfortunately already has a dedicated name. Automatically assuming that those with the power to help will pay attention to a community’s cries is a privilege that many do not have. Abigail Echo-Hawk, an Indigenous activist in Washington—the state with the second-highest rates of MMIWG—wrote an open letter in which she highlighted that privilege. She says that “[l]egislators, government agencies, and media have been forced to pay attention because of the relentless work by the families of MMIWG victims, grassroots activists, tribes, and Native organizations across the country.” Their cases are not investigated, let alone covered, in the media without vigorous community organizing; these resources are not doled out for these communities, they are fought for.

In Washington specifically, Indigenous people represent only 1.9% of the state’s population, yet they account for 6% of active missing person reports. But “the actual number of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls is likely much higher,” as Indigenous persons, just like Latinx people, “are often inaccurately reported or listed as White in law enforcement databases.” Indigenous women go missing at ten times the national average, yet there are no high-profile cases, obsessive social media followings or extraordinary efforts by law enforcement to solve their cases. An activist covering the case of Laverda Sorrell, a Navajo woman who has been missing for 19 years with no resolution, says that the general sentiment around MMIWG is “[a]lmost like we don’t exist. That is what it feels like. So when another Indigenous woman goes missing, it is like you already know, that it is not going to be solved.” Sorrell’s family made a plea to the public for help after the FBI had been aware of her case for over 18 years with no leads. Media coverage is a vital awareness tool for everyday people who may see something and say something, and while cases like Petito’s seem to be all that exist according to the media, those like Sorrell’s are ignored for decades with their loved ones as their only voices.

“Our Black Girls” is a website launched by Erika Marie Rivers in 2018 to tell the stories of unsolved cases involving Black women and girls. Rivers reportedly publishes a new article every other day, and feels motivated to do so because “she could have easily been one of these missing girls and women.” On her website, Rivers asks her readers rhetorically, “[w]hy is it that, according to the National Crime Information Center of the FBI, approximately 33 percent of people reported missing are Black, but that isn’t reflective of the evening news?” According to NPR research in 2020, a third of the over 250,000 missing girls and women were Black, despite the fact that they make up only 13% of the female population in the US. Individual efforts like Rivers’ are a reflection of how little attention these women’s cases receive from the entities that are expected to work for them. Once again, public awareness of marginalized missing people is left up to an activist from the marginalized community fighting for resources that are readily and unquestionably given to more exciting, more worthy victims—white women—at the expense of Black women and girls.

The rate at which women are victimized is an unacceptable tragedy in and of itself, with seemingly no end in sight. Whether people are willing to admit it or not, our society continues to actively support violence against women in many ways; rape culture, domestic violence, and sex trafficking, and the societal conditions that allow for these systemic trends, run as deep as ever. Yet, when media coverage of cases like Gabby Petito’s inundate the social media timelines and news feeds of loved ones of non-white women victims, it must feel like the world is against them. In many ways, it is. All of this is not to say that Gabby Petito, and all missing and murdered white women, do not deserve recognition. The respective resolutions of their cases are the smallest celebrations within the unimaginable grief that comes with their disappearances. But the care with which their cases are handled should not come at the expense of others, nor should they be given higher priority. We cannot ignore that those who are marginalized by society are wrongfully the most easily forgotten; we must lean as far as we can in the opposite direction to amplify the voices of people whose stories are filed away in a box that reads unsolved.

Featured Image: Heritage Auctions

Comments are closed.